Warther Museum

Warther Museum

Garden

Pliers Tree

I love art but have little time for the crafts. Crafts being, by my definition, anything involving artificial flowers, wicker, jewelry made out of strings and beads, and homemade dolls. Carving, on the other hand, teeters between art and craft depending on the one doing it. There is, for example, some fellow in the area in which I live who makes these god-awful chainsaw sculptures that he would have to pay me large sums of money to put in front of my house. His sort of carving falls firmly into the category of the crafts. It was therefore with some trepidation that I decided to visit the Warther Museum, in Dover, Ohio, which I knew was mainly the work of some carver I’d never heard of whose wife collected buttons. I needn’t have worried. The museum houses works of art, not crafts. It mainly showcases the carvings of Ernest “Mooney” Warther, a genius on par with Einstein, Leonardo da Vinci, and Benjamin Franklin.

Born in 1883 or 1885 (sources differ) in Dover, Ohio, he was the son of Swiss parents. “Mooney” was his nickname and what most people called him. At the age of five while working as a cowherd, he came across a discarded pocket knife with which he started to whittle. In his early days he made novelty items such as working pairs of pliers carved out of a single unshaved stick of wood. One day he had a sudden inspiration: from one block of wood he would carve hundreds of interconnecting pliers. 30,000 cuts later he had 511 pairs and not a single shaving. When expanded together, they looked like a tree. No one has ever replicated this masterpiece and possibly no one ever can. Mooney had a second grade education and created this by envisioning it, not by planning it out as some elaborate geometric math problem. A photo of it even appeared in a high school math book.

Born in 1883 or 1885 (sources differ) in Dover, Ohio, he was the son of Swiss parents. “Mooney” was his nickname and what most people called him. At the age of five while working as a cowherd, he came across a discarded pocket knife with which he started to whittle. In his early days he made novelty items such as working pairs of pliers carved out of a single unshaved stick of wood. One day he had a sudden inspiration: from one block of wood he would carve hundreds of interconnecting pliers. 30,000 cuts later he had 511 pairs and not a single shaving. When expanded together, they looked like a tree. No one has ever replicated this masterpiece and possibly no one ever can. Mooney had a second grade education and created this by envisioning it, not by planning it out as some elaborate geometric math problem. A photo of it even appeared in a high school math book.

On October 29, 1910, he married Freida Richard. The two had three daughters and two sons, who in turn produced twenty-three grandchildren, the latter begetting nine great-grandchildren at the time of Mooney’s death on June 8, 1973. Despite committing so much time either working or carving, Mooney, whose father died when he was a toddler, spent much time with both his and the neighborhood children. Once, for example, he built a giant sandbox for them. Though talented in many areas, he wasn’t good at everything. According to one museum information sign, he was “a downright terrible driver. After driving the family car in the ditch, with Frieda inside, Mooney was no longer permitted to drive with her” in the vehicle.

On December, 1, 1913, Mooney, inspired in part by a train passing his workshop each day, decided to carve the history of steam power. Most of what he produced would be historically significant steam locomotives. He acquired blueprints, photos, and other references and proceeded to carve each piece of a given item at a reduced scale in his little shack of a workshop. Unlike a traditional carving that shows the outside of an object while remaining just solid within, Mooney carved each individual piece of an object, then assembled the whole. His locomotives worked, some of which he animated with an electric motor. Railroad engineers would marvel at the accuracy of his locomotives and only once did one find that Mooney had missed a piece, a wire that went from the cab to the headlamp. This he quickly fixed.

The models were often made out of locally found black walnut, old billiard balls, and even a cow’s thigh, and sometimes pieces of metal that served as axels. For moving parts, Mooney used Arguto wood, which, according to the Woodex Bearing Company’s website, is “rock maple impregnated with petrolatum wax.” The museum tour made much of the fact that some of the trains have been running since their creation without wearing out or needing new lubrication. Arguto wood is the secret to that success.

On December, 1, 1913, Mooney, inspired in part by a train passing his workshop each day, decided to carve the history of steam power. Most of what he produced would be historically significant steam locomotives. He acquired blueprints, photos, and other references and proceeded to carve each piece of a given item at a reduced scale in his little shack of a workshop. Unlike a traditional carving that shows the outside of an object while remaining just solid within, Mooney carved each individual piece of an object, then assembled the whole. His locomotives worked, some of which he animated with an electric motor. Railroad engineers would marvel at the accuracy of his locomotives and only once did one find that Mooney had missed a piece, a wire that went from the cab to the headlamp. This he quickly fixed.

The models were often made out of locally found black walnut, old billiard balls, and even a cow’s thigh, and sometimes pieces of metal that served as axels. For moving parts, Mooney used Arguto wood, which, according to the Woodex Bearing Company’s website, is “rock maple impregnated with petrolatum wax.” The museum tour made much of the fact that some of the trains have been running since their creation without wearing out or needing new lubrication. Arguto wood is the secret to that success.

The tour lasted six months. For the next two and one-half years, Mooney worked at Grand Central Terminal in New York City showing his work, only coming home for good in the fall of 1926. This venture paid so well it allowed him and his family to buy things they needed. He was also able to afford ebony and ivory. A committed pacifist and animal lover, he only bought the tusks of elephants who had died naturally, though considering the sordid history of ivory hunting then and now, it seems more likely they had in fact been killed for their ivory. He used other types of ivory as well, including that from hippopotami.

In addition to carving, he also collected arrowheads, which he wife arranged into geometric displays. Freida was an overachiever just like her husband. In addition to being a busy homemaker, she also created a fabulous garden and collected buttons, 73,000 of them. The latter she didn’t just stick in a jar someone. Instead she arranged them into aesthetically-pleasing geometric shapes, which now cover the walls of a small building next to their house, through which visitors can also go.

In addition to carving, he also collected arrowheads, which he wife arranged into geometric displays. Freida was an overachiever just like her husband. In addition to being a busy homemaker, she also created a fabulous garden and collected buttons, 73,000 of them. The latter she didn’t just stick in a jar someone. Instead she arranged them into aesthetically-pleasing geometric shapes, which now cover the walls of a small building next to their house, through which visitors can also go.

Mooney considered the Great Northern Locomotive his best work.

Mooney’s hero was Abraham Lincoln. As a tribute to this president, he carved several walking sticks with Lincoln’s head at its top and did a carving of Lincoln’s funeral train. Just to show how much attention he paid to details, in one part of a car there is a key that opens the locked restroom in another part! Another amazing carving he produced is a replica of the mill he once worked in, complete with figures representing real former coworkers, some of which are animated. This he created from memory some twenty years after leaving the mill.

As my traveling companions and I went through the museum, I asked the tour guide if Mooney ever sold his carvings. Not a one! Mooney never made a penny by selling them, insisting he wanted carving to be his hobby, not work. This is true, but it doesn’t mean he didn’t benefit financially from his trains. In 1927 his brother, Fred, took them on the road, the proceeds from this paying for a tour truck, the tour itself, Fred’s salary, and more materials for future carvings. Mooney did multiple versions of works, in part so one version would be in Dover itself for people to see while the other was out on tour. He made five versions, for example, of the Empire State Express, the 999, the same engine that pulled the Service Progress Special. During the Depression the Mooney family, like everyone else, was hit hard. For twelve years Mooney did few carvings, though from September 23, 1932, to May 1, 1933, he created the Great Northern Locomotive, which he considered his best effort. If you see his other, later work, you might disagree. He never carved a diesel-electric engine because these machines he hated.🕜

As my traveling companions and I went through the museum, I asked the tour guide if Mooney ever sold his carvings. Not a one! Mooney never made a penny by selling them, insisting he wanted carving to be his hobby, not work. This is true, but it doesn’t mean he didn’t benefit financially from his trains. In 1927 his brother, Fred, took them on the road, the proceeds from this paying for a tour truck, the tour itself, Fred’s salary, and more materials for future carvings. Mooney did multiple versions of works, in part so one version would be in Dover itself for people to see while the other was out on tour. He made five versions, for example, of the Empire State Express, the 999, the same engine that pulled the Service Progress Special. During the Depression the Mooney family, like everyone else, was hit hard. For twelve years Mooney did few carvings, though from September 23, 1932, to May 1, 1933, he created the Great Northern Locomotive, which he considered his best effort. If you see his other, later work, you might disagree. He never carved a diesel-electric engine because these machines he hated.🕜

Warther started his history of steam power with a design by Sir Isaac Newton that was never built in its time, then moved on to an engine made by Englishman Willard Murdock. The closer to his own time he got, the more complicated Mooney’s carvings became. He managed all this while laboring eight hours a day at the local American Sheet & Tin Can plant, a dangerous line of work not for the feint of heart and one that didn’t pay all that well. Dedicated to his hobby, Mooney told the Plain Dealer each day he got up at three in the morning to carve before everyone rose for the day and started to sidetrack him.

For extra money he made knives, mainly for kitchens, which he later produced full time. These are still being made in a workshop in the basement of the museum, though it will be moving into its own place next year. Speaking of knives, Mooney periodically constructed his own for carving, one that fit his hand perfectly and had interchangeable blades that snapped in place via a spring loading system. To this day only his family possesses these; they’ve never been made commercially.

For extra money he made knives, mainly for kitchens, which he later produced full time. These are still being made in a workshop in the basement of the museum, though it will be moving into its own place next year. Speaking of knives, Mooney periodically constructed his own for carving, one that fit his hand perfectly and had interchangeable blades that snapped in place via a spring loading system. To this day only his family possesses these; they’ve never been made commercially.

Empire State Express

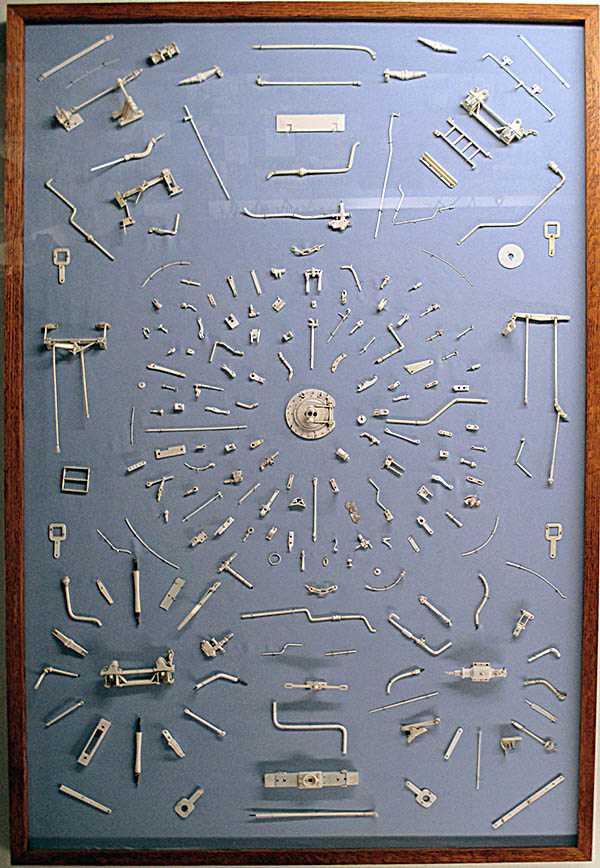

Empire State Express in Pieces

In 1923 Mooney was approached by the New York Central Railroad to take his steam locomotives on a tour of America via the railroad. He readily agreed, quitting his job to do so. Called the Service Progress Special, the tour was really a promotional tool for New York Central, but it benefited Mooney as well. According to a Plain Dealer article, the train carrying him and his carvings traveled 12,000 miles with over 700,000 people across the country viewing his work. The engine pulling this display was the famous “999,” which once set the speed record for a steam locomotive by reaching 112.5 mph.

Although the plaque says this is a steam engine, it's really a steam canon.

Warther Family House

Mooney often carved pliers like these made from a single piece of wood from shavings after completing a part or job.

Steel Mill Diorama

Figure from the Steel Mill Diorama

Frieda Warther's Button Collection