Wolcott Heritage Center

Wolcott House

Maumee River Across from the Wolcott House

Mary Ann Wolcott-Gilbert painted this on the transom above a door in the parlor.

Basement in the Wolcott House

Bedroom in the Wolcott House

Wolcott House's Garden

Wolcott House's Upstairs

As he entered his last years, James Wolcott's hearing declined, so he used this ear trumpet in an effort to improve things. They didn't help all that much.

Rilla Hull

Native American Display in the Wolcott House

This table and chair set is in the Wolcott House's parlor.

Gilbert-Flanigan House

The Gilbert-Flanigan house before its restoration.

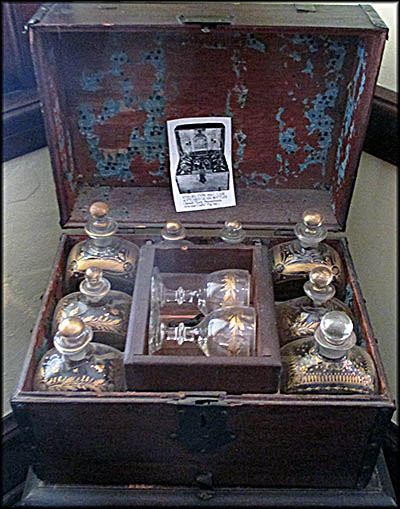

This set of glass cups and bottles is on display in the Wolcott House.

Gilbert-Flanigan House's Kitchen

Log House

Caboose at the Clover Leaf Depot

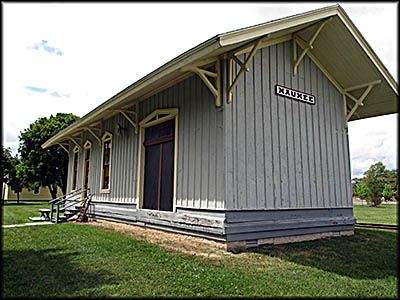

Clover Leaf Depot

Monclova County Church

Victorian-Era Objects Display in the Wolcott House

Northwest Ohio isn’t my favorite place to drive through because of its flat, treeless landscape covered with farm fields as far as the eye can see. There are exceptions, and one of them is the valley through which the Maumee River empties into Lake Erie. At the top of the valley’s northern side in the city of Maumee stands a house built in 1827 by James and Mary Wolcott that serves as the centerpiece of the Wolcott House Heritage Center, James and Mary chose to build in Maumee because at this point the river was still navigable, and at the time they moved in, the Miami & Erie Canal passed through. This artificial waterway, which started in Toledo and ended in Cincinnati, connected Lake Erie to the Ohio River.

James gambled that Maumee would become the Lake Erie port of Northwest Ohio, and to that end he built docks here for his shipping business. As the decades went by, larger vessels were unable to reach Maumee, so that didn’t happen. Despite this, Wolcott’s shipping business was a success that made him quite wealthy. He also ran a general store, bought and sold land in what are now Lucas and Wood Counties, and farmed.

James gambled that Maumee would become the Lake Erie port of Northwest Ohio, and to that end he built docks here for his shipping business. As the decades went by, larger vessels were unable to reach Maumee, so that didn’t happen. Despite this, Wolcott’s shipping business was a success that made him quite wealthy. He also ran a general store, bought and sold land in what are now Lucas and Wood Counties, and farmed.

Born into a prominent Connecticut family on November 3, 1789—his uncle Oliver Wolcott signed the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation—James first came to Ohio in 1818. He settled in Delaware at which he started a woolen goods factory. Two years later he moved to St. Louis where he met and married Mary Wells, who was born in 1800. Her father was William Wells, who as a child between eight and fourteen years of age was abducted by Myaamia (Miami) warriors in Kentucky. Wolcott family lore claims the raiding party that kidnapped him was led by Chief Little Turtle, who later led a coalition to oust Americans from Ohio. William and his younger brother were caught by the raiders while out playing. Upon being grabbed by a warrior, the younger brother starting wailing. As the warrior who’d seized him made to strike the boy with a tomahawk, William caught his arm and hit it. This caused the other Miamis to laugh, so they let the younger brother go and took William with them.

William was adopted by Chief Gaviahate (Porcupine) and given the nickname “Apekonit,” which meant “carrot,” a reference to his red hair. He lived in a village along the Eel River in Indiana. Learning the Miami’s language, he became a warrior and was among those who successfully routed General Arthur St. Clair’s army at the Wabash River on November 4, 1791. He married a woman in the tribe and together they produced a child. She and the child were later captured by Americans and presumed dead. He remarried, this time to Little Turtle’s daughter, Wanagapeth (Sweet Breeze). Unbeknownst to him, his first wife and child were still alive. Upon learning of this, he secured their release but afterward cut all ties with them.

William was adopted by Chief Gaviahate (Porcupine) and given the nickname “Apekonit,” which meant “carrot,” a reference to his red hair. He lived in a village along the Eel River in Indiana. Learning the Miami’s language, he became a warrior and was among those who successfully routed General Arthur St. Clair’s army at the Wabash River on November 4, 1791. He married a woman in the tribe and together they produced a child. She and the child were later captured by Americans and presumed dead. He remarried, this time to Little Turtle’s daughter, Wanagapeth (Sweet Breeze). Unbeknownst to him, his first wife and child were still alive. Upon learning of this, he secured their release but afterward cut all ties with them.

In 1793 he joined General Anthony Wayne’s army as it aimed to defeat the aforementioned coalition of Native Americans from Ohio. Sources aren’t clear as to why Wells decided to join the Americans, but in any case, Wayne hired him to lead his scouts. Another story from Wolcott family lore has Wells leading his scouts to the banks of the Auglaize River where they saw a canoe with a number of Native Americans in it. As his men readied to fire at them, Wells warned, “I will shoot the first man that attempts to injure these Indians. They are my father, my wife and children.” His “father” was none other than Little Turtle, who was taking Wells’s wife and children to safety. This story is probably apocryphal. Had the Americans really found Little Turtle without an escort of warriors, they would’ve made him their captive.

Wayne defeated the coalition of indigenous people at the Battle of Fallen Timbers on August 20, 1794. Not far from the battle site along the banks of the Maumee River, the British had recently erected Fort Miami in what is now the city of Maumee. Armed with fourteen cannons and holding 130 British soldiers, the defeated Native Americans came here for protection but were turned away.

Wells didn’t participate in the Battle of Fallen Timbers because he was wounded in the wrist during a scouting expedition shortly before it. After the battle, he served as an interpreter at Fort Greenville where a peace treaty was hashed out. For the next ten years he was an Indian Agent. He returned to military service during the War of 1812 and was killed on August 15, 1812, near what is today Chicago.

He and Sweet Breeze had four children: one son and three daughters. Sweet Breeze died during the winter of 1804–1805. With the outbreak of the War of 1812, Wells sent his children to live in Louisville, Kentucky, with their uncle, Samuel Wells. Here Mary was raised to be a Southern belle.

Wayne defeated the coalition of indigenous people at the Battle of Fallen Timbers on August 20, 1794. Not far from the battle site along the banks of the Maumee River, the British had recently erected Fort Miami in what is now the city of Maumee. Armed with fourteen cannons and holding 130 British soldiers, the defeated Native Americans came here for protection but were turned away.

Wells didn’t participate in the Battle of Fallen Timbers because he was wounded in the wrist during a scouting expedition shortly before it. After the battle, he served as an interpreter at Fort Greenville where a peace treaty was hashed out. For the next ten years he was an Indian Agent. He returned to military service during the War of 1812 and was killed on August 15, 1812, near what is today Chicago.

He and Sweet Breeze had four children: one son and three daughters. Sweet Breeze died during the winter of 1804–1805. With the outbreak of the War of 1812, Wells sent his children to live in Louisville, Kentucky, with their uncle, Samuel Wells. Here Mary was raised to be a Southern belle.

Later, Sameul moved with his foster children to St. Louis where Mary and James met and married. The couple made they way down the Maumee River to the city of Maumee with their worldly goods upon a pirogue (a large canoe) powered by two Frenchmen. He and Mary had six children. Of them died in infancy and another, Robert Fulton, drowned at the age of twelve in the Maumee River. Mary was, according to a museum information sign, a “zealous Episcopalian.” She and her husband founded Maumee’s first Episcopalian church, which began as a log chapel.

Forty-two when she died, neither the museum nor any of the sources about her that I found mention her cause of death. James remarried, making Caroline B. Davis his second bride. The union ended in divorce. Afterwards, one of his daughters from his first marriage, Mary Ann, moved back to Wolcott House along with her husband, Smith Gilbert, and their children. Mary Ann was quite the artist and had attended the Canandaigua Seminary in the State of New York. When her father died in 1873, the house passed to her. Her husband, it ought to be noted, served as Maumee’s mayor for four terms from April 4, 1859, to April 1, 1867.

Forty-two when she died, neither the museum nor any of the sources about her that I found mention her cause of death. James remarried, making Caroline B. Davis his second bride. The union ended in divorce. Afterwards, one of his daughters from his first marriage, Mary Ann, moved back to Wolcott House along with her husband, Smith Gilbert, and their children. Mary Ann was quite the artist and had attended the Canandaigua Seminary in the State of New York. When her father died in 1873, the house passed to her. Her husband, it ought to be noted, served as Maumee’s mayor for four terms from April 4, 1859, to April 1, 1867.

The last of the Wolcott line to live in the house was Rilla E. Hull, who was James’s and Mary’s great-granddaughter. She never married and made a living operating a long distance switchboard in her house. An active member of St. Paul’s Episcopalian Church, she was proud of her heritage and wanted to preserve the house. To that end she willed it her church, which received the property upon her death in 1957. Opened as a museum in 1961, it was sold the city of Maumee and is curated by the Maumee Historical Society.

The house tour is guided. Throughout there are signs containing passages on etiquette reprinted from nineteenth century sources. One from 1893, for example, says, “It is the duty of a gentleman to know how to ride, to shoot, to fence, to box, to swim, to row, and to dance. He should be graceful. If attacked by ruffians, a man should be able to defend himself, and also defend women against their insults.” Based on this, I can safely say I’m no gentleman. But few if anyone could possibly meet these high expectations, although I can think of at least one historical figure from that era who could: Theodore Roosevelt.

The Wolcott House is one of six historic buildings on the museum’s property. On the day I visited, I was handed off to a different guide to tour its out buildings. First up was the museum’s log house, which was built around 1853. It once stood along the Miami & Erie Canal between Elizabeth and White Streets in Maumee. One of its earliest inhabitants was a French-Canadian, Noah Navare, but it’s not likely he or his family built it. It had several owners, and when railroader James Love purchased it in 1893, he covered the dirt floor with a wooden one and added a front porch. The house was moved twice, once to Wayne Pfleghaar to West Wayne Street, then to the museum's grounds. My tour guide said that its loft was used for storage and not sleeping, but the museum’s website contradicts this, saying, “Children and visitors would often sleep in the loft overhead.”

The house tour is guided. Throughout there are signs containing passages on etiquette reprinted from nineteenth century sources. One from 1893, for example, says, “It is the duty of a gentleman to know how to ride, to shoot, to fence, to box, to swim, to row, and to dance. He should be graceful. If attacked by ruffians, a man should be able to defend himself, and also defend women against their insults.” Based on this, I can safely say I’m no gentleman. But few if anyone could possibly meet these high expectations, although I can think of at least one historical figure from that era who could: Theodore Roosevelt.

The Wolcott House is one of six historic buildings on the museum’s property. On the day I visited, I was handed off to a different guide to tour its out buildings. First up was the museum’s log house, which was built around 1853. It once stood along the Miami & Erie Canal between Elizabeth and White Streets in Maumee. One of its earliest inhabitants was a French-Canadian, Noah Navare, but it’s not likely he or his family built it. It had several owners, and when railroader James Love purchased it in 1893, he covered the dirt floor with a wooden one and added a front porch. The house was moved twice, once to Wayne Pfleghaar to West Wayne Street, then to the museum's grounds. My tour guide said that its loft was used for storage and not sleeping, but the museum’s website contradicts this, saying, “Children and visitors would often sleep in the loft overhead.”

Next we stopped in the dusty, stuffy Gilbert-Flanigan House in which I kept coughing because of allergies. This was built around 1841 and relocated from a different part of Maumee. For a time it belonged to the University of Toledo, which neglected it. The museum bought it, moved it to its grounds, then restored it. Known as an “Ohio Saltbox” because of its resemblance to this type of storage device common in the nineteenth century, inside are many artifacts showing how a farm family lived in the 1800s. Whoever resided here was clearly well off, because the place is huge and while plain compared to the Wolcott House, it is clearly on the higher end of structures of its type. It has, for example, closets, something most homes of this era didn’t include because they counted as rooms and houses were taxed on their number. Neither the tour guide nor the Wolcott Heritage Center’s website had anything to say about the lives of the people who lived here.

From here we went to the Clover Leaf Depot. Built around 1888 to serve the Toledo & Grand Rapids Railroad, outside are a box car and caboose. Railroad enthusiasts will be pleased to know that you can go inside the caboose. Its notably feature is a toilet that opens directly to the tracks below, making them an open sewer. The one room schoolhouse, erected around 1850, is larger than most I’ve seen. The Monclova County Church, constructed around 1901, once served the Radical United Brethren in Monclova whose first bishop was Milton Wright, the father of airplane inventors Orville and Wilbur.🕜

From here we went to the Clover Leaf Depot. Built around 1888 to serve the Toledo & Grand Rapids Railroad, outside are a box car and caboose. Railroad enthusiasts will be pleased to know that you can go inside the caboose. Its notably feature is a toilet that opens directly to the tracks below, making them an open sewer. The one room schoolhouse, erected around 1850, is larger than most I’ve seen. The Monclova County Church, constructed around 1901, once served the Radical United Brethren in Monclova whose first bishop was Milton Wright, the father of airplane inventors Orville and Wilbur.🕜