Ziibiwing Center

Stone Tools and Pelts

Ziibiwing Center Entrance

Inside the Ziibiwing Center

Making Petroglyphs

Processing Rice

Anishninable Man Dressed for Winter

Wigwam

Signing a Treaty

Teaching Lodge

The Anishnakek are excellent artists.

Cradleboard used to carry a baby.

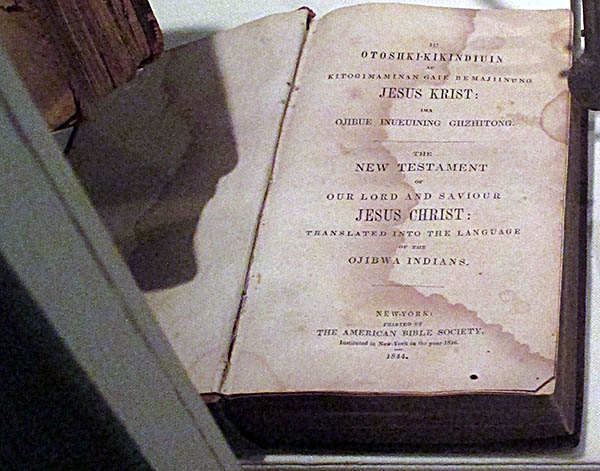

This Bible is in both English and Anishinabemowin, the Anishnakek's language.

Anishnakek-made baskets.

The Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan are culturally and linguistically part of the Anishnakek people. They run both the Soaring Eagle Casino & Resort and the Ziibiwing Center in Mount Pleasant, Michigan, on the Isabella Reservation. The Ziibiwing Center is a museum designed to educate non-Anishnakek about their culture and history. As museums go, it’s one of the best I’ve seen when it comes to exhibit design, layout, information signs, and, critically, it uses well-crafted sculpted figures and not store manikins to represent people.

Most Anishnakek believe the Gitche Manido (Creator) put them along the East Coast and sent them the Seven Prophecies, which guide them to this day. Each prophecy is assigned a number and fire. The fourth one, example, is the Fourth Fire. It warns that the Light-Skinned people (a polite description of those who are either from Europe or of European descent) “will come over the Great Salt Water. They would travel in big trees pulled by billowing white clouds.” Some may be friendly, others deceitful and dangerous. The Seven Prophecies are the one of the tenants of their culture, the equivalent of the Bible for Jews and Christians, Vedas for Hindus, and Tripitakas for Buddhism. The Seven Prophecies guide the Anishnakek to this day.

In 796 c.e., the Ishkodaywatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe nations formed the Three Fires Confederacy. Around 900 c.e. the Anishnakek, prompted by the Seven Prophecies and conflict with other native peoples, began migrating west, settling along the Great Lakes in what is today both the United States and Canada. This migration is known as the Great Walk, and the people were told they had to stop for a time at seven locations.

Most Anishnakek believe the Gitche Manido (Creator) put them along the East Coast and sent them the Seven Prophecies, which guide them to this day. Each prophecy is assigned a number and fire. The fourth one, example, is the Fourth Fire. It warns that the Light-Skinned people (a polite description of those who are either from Europe or of European descent) “will come over the Great Salt Water. They would travel in big trees pulled by billowing white clouds.” Some may be friendly, others deceitful and dangerous. The Seven Prophecies are the one of the tenants of their culture, the equivalent of the Bible for Jews and Christians, Vedas for Hindus, and Tripitakas for Buddhism. The Seven Prophecies guide the Anishnakek to this day.

In 796 c.e., the Ishkodaywatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe nations formed the Three Fires Confederacy. Around 900 c.e. the Anishnakek, prompted by the Seven Prophecies and conflict with other native peoples, began migrating west, settling along the Great Lakes in what is today both the United States and Canada. This migration is known as the Great Walk, and the people were told they had to stop for a time at seven locations.

The first stop is at what is today Montreal in Quebec. Here they made a turtle-shaped island in the St. Lawerence River. Next, they stopped at Niagara Falls, then in the St. Claire-Detroit River area the rapids. Manitoulin Island in Ontario served as the fourth stop. Sault Ste. Marie (a city in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula) was the fifth stop. Spirit Island in today’s Duluth, Minnesota, was the sixth stop. The trek ended at Madeline Island in Lake Superior off the shore of western Wisconsin. Not all on the Great Walk made it this far. At each stop some broke off and settled where they were, explaining why the Anishnakek are so widespread.

The Anishnakek recorded their culture, history and religious ceremonies using oral histories, petroglyphs and, from at least the 1500s, wiigwaas (birchbark) scrolls. Many if not all their songs, ceremonies, stories, and prayers preceded contact with the Light-Skinned people. They used the kinoomaagegamik (teaching lodge) to educate their people. Some of their knowledge was passed on to the Light-Skinned people, such as how to tap maple trees for their syrup, then boil it down into an edible form. The Anishnakek used maple syrup to flavor everything from wild rice to moose to bear. They also traded it.

Like the rest of the human race, the Anishnakek had to accomplish different things during the four seasons of the year. In the summer, fish were caught and smoked for long term storage. They made or repaired birchbark canoes and grew gardens. In late summer and early fall they harvested wild rice, which grew in lakes and slow-flowing streams and rivers.

The Anishnakek recorded their culture, history and religious ceremonies using oral histories, petroglyphs and, from at least the 1500s, wiigwaas (birchbark) scrolls. Many if not all their songs, ceremonies, stories, and prayers preceded contact with the Light-Skinned people. They used the kinoomaagegamik (teaching lodge) to educate their people. Some of their knowledge was passed on to the Light-Skinned people, such as how to tap maple trees for their syrup, then boil it down into an edible form. The Anishnakek used maple syrup to flavor everything from wild rice to moose to bear. They also traded it.

Like the rest of the human race, the Anishnakek had to accomplish different things during the four seasons of the year. In the summer, fish were caught and smoked for long term storage. They made or repaired birchbark canoes and grew gardens. In late summer and early fall they harvested wild rice, which grew in lakes and slow-flowing streams and rivers.

Rice was stored for use in winter, during which extended families moved into a winter lodge. During this relatively idle time they recited oral histories, composed songs, and told stories, passing their history and culture to the next generation. Outside, traps were put out for small game. Repairs were made to clothing, fishing nets, tools, and anything else that needed fixing.

For about the first 200 years after their arrival, the European presence in North America benefited the Anishnakek by allowing them to trade for items previously unknown to them. In exchange for furs, the Europeans gave them metal objects such as axes, knives, and cook pots. The Anishnakek also traded for clothes, glass beads, needles and threads. The introduction of glass beads in particular resulted the stunning decoration of clothes and objects. Early European explorers adopted Anishnakek words as their own. The Anishnakek word for big water, “mishigami,” as an example, turned into “Michigan.”

The arrival of white settlers changed the face of Michigan forever, altering the Anishnakek’s way in catastrophic ways. Trapping and hunting ended when the lumber industry moved in and stripped the majority of Michigan’s forests, this habitat loss causing many plants and animals to either disappear or become scarce. Sweetgrass, one of the Anishnakek’s most sacred medicines, is virtually extinct in Michigan. The populations of elks, wolverines, sturgeons and many other food sources for the Anishnakek crashed.

For about the first 200 years after their arrival, the European presence in North America benefited the Anishnakek by allowing them to trade for items previously unknown to them. In exchange for furs, the Europeans gave them metal objects such as axes, knives, and cook pots. The Anishnakek also traded for clothes, glass beads, needles and threads. The introduction of glass beads in particular resulted the stunning decoration of clothes and objects. Early European explorers adopted Anishnakek words as their own. The Anishnakek word for big water, “mishigami,” as an example, turned into “Michigan.”

The arrival of white settlers changed the face of Michigan forever, altering the Anishnakek’s way in catastrophic ways. Trapping and hunting ended when the lumber industry moved in and stripped the majority of Michigan’s forests, this habitat loss causing many plants and animals to either disappear or become scarce. Sweetgrass, one of the Anishnakek’s most sacred medicines, is virtually extinct in Michigan. The populations of elks, wolverines, sturgeons and many other food sources for the Anishnakek crashed.

Much of the cleared land was repurposed for farming, and the pioneers who worked them brought diseases like smallpox, influenza and tuberculosis. These decimated the Anishnakek population, reducing it from one-third to one-half. Orphans who survived epidemics died anyway because no one was left to care for them.

When Andrew Jackson became president, things got a whole lot worse. Jackson saw Native Americans as an impediment to U.S. expansion and prosperity, and aimed to send them all west of the Mississippi. Despite the ruling by the Supreme Court that the Cherokees were entitled to self-govern their lands in Georgia, Jackson ordered the U.S. Army to forcibly remove them and four other Southern tribes to Mississippi, an action known today as the Trail of Tears because of all those native people who died during this terrible trek.

The architect of “Indian removal” was Lewis Cass. He served as Jackson’s Secretary of War and oversaw Indian removal. During his time as Michigan’s territorial governor from 1813 to 1831, he negotiated multiple treaties to trick or coerce the Anishnakek to go west. Treaty negotiations involved lots of alcohol to ensure the Anishnakek had impaired judgement. One information sign says, “It was intentionally used a weapon of exploitation.” While thousands of Anishnakek were removed to western reserves, some stubbornly remained in their homes.

When Andrew Jackson became president, things got a whole lot worse. Jackson saw Native Americans as an impediment to U.S. expansion and prosperity, and aimed to send them all west of the Mississippi. Despite the ruling by the Supreme Court that the Cherokees were entitled to self-govern their lands in Georgia, Jackson ordered the U.S. Army to forcibly remove them and four other Southern tribes to Mississippi, an action known today as the Trail of Tears because of all those native people who died during this terrible trek.

The architect of “Indian removal” was Lewis Cass. He served as Jackson’s Secretary of War and oversaw Indian removal. During his time as Michigan’s territorial governor from 1813 to 1831, he negotiated multiple treaties to trick or coerce the Anishnakek to go west. Treaty negotiations involved lots of alcohol to ensure the Anishnakek had impaired judgement. One information sign says, “It was intentionally used a weapon of exploitation.” While thousands of Anishnakek were removed to western reserves, some stubbornly remained in their homes.

The federal government decided to deal with these holdouts with forced cultural assimilation. Missionaries were encouraged to establish schools, resulting in many Anishnakek converting to Christianity. Hymn books and the Bible were translated into Anishinabemowin, the Anishnakek’s language. To this day many young Anishnakek don’t speak Anishinabemowin. Fortunately, programs to teach it to them are reversing this reality.

Anishnakek children were forced to attend boarding schools for nine or more months out of each year. Some schools were hundreds of miles from the children’s homes. The schools forbade the speaking of native languages, taught Christianity, marched the children like soldiers, and did everything possible to keep them from leaning their own culture during these critical years of development. Many children grew to adulthood knowing little if anything about their own language, culture and history. Parents, during the brief time they saw their children, didn’t have enough time to learn good parenting skills. These schools left a terrible scar on the Anishnakek, which they feel to this day.

One of these schools was in Mt. Pleasant near where the Ziibiwing Center stands, and its buildings are still there. Upon learning this, I thought I’d like to get a photo of its exterior if possible. When I asked those working at the Center how to get there, I was told it’s open on rare occasions (one being a week or so before I visited), and that no one was allowed on the grounds. I did find it, but trees hid most of it—thus no photo.

Without lands on which they could hunt and gather, the Anishnakek fell into great poverty. In the early twentieth century some Anishnakek began selling their beautiful baskets to survive. It didn’t make them rich, but at least it kept them from going hungry. Another thing that got some through these hard times was Christianity and its camp meetings.

Anishnakek children were forced to attend boarding schools for nine or more months out of each year. Some schools were hundreds of miles from the children’s homes. The schools forbade the speaking of native languages, taught Christianity, marched the children like soldiers, and did everything possible to keep them from leaning their own culture during these critical years of development. Many children grew to adulthood knowing little if anything about their own language, culture and history. Parents, during the brief time they saw their children, didn’t have enough time to learn good parenting skills. These schools left a terrible scar on the Anishnakek, which they feel to this day.

One of these schools was in Mt. Pleasant near where the Ziibiwing Center stands, and its buildings are still there. Upon learning this, I thought I’d like to get a photo of its exterior if possible. When I asked those working at the Center how to get there, I was told it’s open on rare occasions (one being a week or so before I visited), and that no one was allowed on the grounds. I did find it, but trees hid most of it—thus no photo.

Without lands on which they could hunt and gather, the Anishnakek fell into great poverty. In the early twentieth century some Anishnakek began selling their beautiful baskets to survive. It didn’t make them rich, but at least it kept them from going hungry. Another thing that got some through these hard times was Christianity and its camp meetings.

Despite all the obstacles against them, the Anishnakek and their culture remain. They’ve implemented their own environmental preservation programs to restore habitat for wildlife to allow them to once again hunt and fish. An information sign says they “stock more fish in the Great Lakes than the U.S. government.”

Although the Anishnakek didn’t have a warrior culture, they nonetheless could and did fight if the need arose. During the Civil War, 139 Anishnakek men joined 1st Michigan’s Company K that had a single white man, the officer, this because of the day’s racist attitudes. Today, Native Americans have the highest enlistment rate in the U.S. armed services of any ethnic group. The Anishnakek also consider those who protect the environment, fishing and hunter warriors.

On the Isabella Reservation, the Tomah Club, an Anishnakek social club, began running bingo games for fundraising in the 1960s. People played from their cars, honking their horns to indicate they’d gotten a bingo. At that time the unemployment rate among the Anishnakek was about seventy-five percent. Since then, the running of the Soaring Eagle Casino & Resort has reduced that number to near zero. These days, the Isabella Reservation has its own fire and police departments, courts, and schools. It gives two percent of its profits to Isabella County.

NOTE: Spellings of Anishnakek words came from the Center’s information signs. “Anishnakek” is the plural of “Anishinable.”🕜

Although the Anishnakek didn’t have a warrior culture, they nonetheless could and did fight if the need arose. During the Civil War, 139 Anishnakek men joined 1st Michigan’s Company K that had a single white man, the officer, this because of the day’s racist attitudes. Today, Native Americans have the highest enlistment rate in the U.S. armed services of any ethnic group. The Anishnakek also consider those who protect the environment, fishing and hunter warriors.

On the Isabella Reservation, the Tomah Club, an Anishnakek social club, began running bingo games for fundraising in the 1960s. People played from their cars, honking their horns to indicate they’d gotten a bingo. At that time the unemployment rate among the Anishnakek was about seventy-five percent. Since then, the running of the Soaring Eagle Casino & Resort has reduced that number to near zero. These days, the Isabella Reservation has its own fire and police departments, courts, and schools. It gives two percent of its profits to Isabella County.

NOTE: Spellings of Anishnakek words came from the Center’s information signs. “Anishnakek” is the plural of “Anishinable.”🕜

Stages of Making Maple Syrup