Beaufort History Museum

One of the houses in Beaufort.

Beaufort History Museum's Courtyard

Beaufort History Museum's Entrance

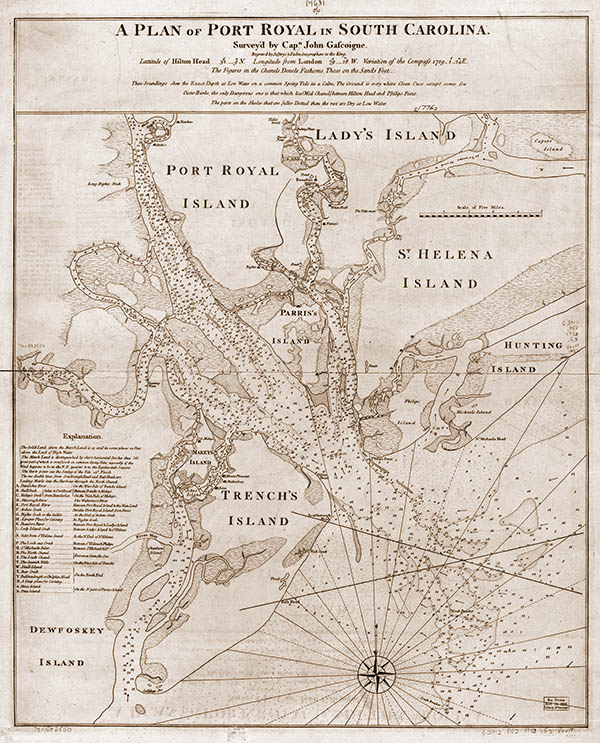

A plan of Port Royal in South Carolina. Drawn by John Gascoigne. London: Jefferys and Faden, 1773(?). Library of Congress.

If you want to visit the Beaufort History Museum, come with a lot of quarters, a credit card, or download the town of Beaufort’s parking app. You’ll need one of these because the words “free parking” in this South Carolinian town could well result in a riot if spoken too loud. Now while I expect to pay for parking in large cities, I didn’t think it’s be so expensive and expansive as I found it in Beaufort (rhymes with you-fert). It has a population of just over 13,000, making it smaller than the town in which I live where free parking is the rule rather than the exception. For Beaufort, parking fees are so lucrative, the city has its own website dedicated to figuring out where you can park and how much you should expect to pay.

Inside the Museum

Before visiting the museum, my traveling companions decided to take a horse-drawn carriage tour of the town from the Sea Island Carriage Company, which was kind enough to delay departure so we could pay for our tickets and visit the restrooms. The horse pulling our carriage was laidback. His ability to move was hindered by his desire stay put. At one point he stalled in the middle of an intersection. At the behest of our guide, we waved to the cars being blocked. As we passed the Rhett House Inn, I cheekily asked if it was owned by the Rhett Butler’s family. (For those unaware, he’s a character in Gone with the Wind.) To my surprise, I learned that Margarite Mitchell visited Beaufort while writing her novel, and did lift the name Rhett from that town’s family.

After the carriage ride, we did some shopping (not in art galleries) and ate a quick lunch. Then we headed to the Beaufort History Museum, which is located in the Arsenal, a beautiful fort-like building constructed in 1798 for weapons storage and to serve as the headquarters of the Beaufort Volunteer Artillery. You enter on the lower floor. The museum proper covers the entirety of the building’s upper floor.

The museum examines the history of entire peninsula upon which Beaufort stands, a region that includes Parris Island and Port Royal. Before the arrival of Europeans, the area was populated by the Orista and Escamaçu. Then came the Spanish, who were smelly (they didn’t bathe) and carried unknown diseases that decimated the local population. In 1576, the Orista allied with the Guale to the south and tried to drive them out, but failed.

After the carriage ride, we did some shopping (not in art galleries) and ate a quick lunch. Then we headed to the Beaufort History Museum, which is located in the Arsenal, a beautiful fort-like building constructed in 1798 for weapons storage and to serve as the headquarters of the Beaufort Volunteer Artillery. You enter on the lower floor. The museum proper covers the entirety of the building’s upper floor.

The museum examines the history of entire peninsula upon which Beaufort stands, a region that includes Parris Island and Port Royal. Before the arrival of Europeans, the area was populated by the Orista and Escamaçu. Then came the Spanish, who were smelly (they didn’t bathe) and carried unknown diseases that decimated the local population. In 1576, the Orista allied with the Guale to the south and tried to drive them out, but failed.

So why had the Spanish come in the first place? Greed, mostly. They called the area spanning from the Florida Keys to Newfoundland La Florida. Claiming it all for themselves, they aimed to keep other European nations out. Despite this, the first Europeans to establish a foothold on here were the French in 1562. Sent by Gaspart de Coligny, they were led by Captain Jean Ribaut, who gave Port Royal its name. He and his men built Charlesfort on what is now Parris Island to serve as a place where Huguenots could move to escape Catholic persecution in France. When Ribaut failed to return with supplies because of a delay caused by war in Europe, his starving men constructed a boat and sailed south to establish Fort Caroline.

In 1566, Florida’s Spanish governor, Pedro Mendéndez de Avilés, established the town of Santa Elena here as his capital. The Spanish abandoned the settlement in 1584. One hundred years later, Scots at the behest of the Carolinian Lords Proprietors founded Stuart’s Town near the spot where Beaufort now stands. It didn’t last. The Spanish burned it to cinders in 1586.

The Yamasee from the Carolinian interior moved into the Port Royal area and established ten towns that they inhabited from 1695 to 1715. They came as allies of the British to serve as a buffer between English settlements to the north and Spanish ones to the south. The English moved in as well. The town of Beaufort was established on January 17, 1711, and took its name from Henry Somerset, Duke of Beaufort. It turned out to be in the heart of what would soon become a dangerous place. British traders often collected debts from the Yamasee by taking their children, women and livestock. In 1715, the Yamasee decided to drive the British out. During the resulting war, Beaufort was destroyed. A militia from Charles Town eventually routed the Yamasee, sending them south of the Savanna River.

In 1566, Florida’s Spanish governor, Pedro Mendéndez de Avilés, established the town of Santa Elena here as his capital. The Spanish abandoned the settlement in 1584. One hundred years later, Scots at the behest of the Carolinian Lords Proprietors founded Stuart’s Town near the spot where Beaufort now stands. It didn’t last. The Spanish burned it to cinders in 1586.

The Yamasee from the Carolinian interior moved into the Port Royal area and established ten towns that they inhabited from 1695 to 1715. They came as allies of the British to serve as a buffer between English settlements to the north and Spanish ones to the south. The English moved in as well. The town of Beaufort was established on January 17, 1711, and took its name from Henry Somerset, Duke of Beaufort. It turned out to be in the heart of what would soon become a dangerous place. British traders often collected debts from the Yamasee by taking their children, women and livestock. In 1715, the Yamasee decided to drive the British out. During the resulting war, Beaufort was destroyed. A militia from Charles Town eventually routed the Yamasee, sending them south of the Savanna River.

When the American Revolution broke out, it wasn’t just a war from independence from Britain. It turned into a civil war between Patriots and Loyalists. The issue only worsened when the British increased military operations in the South starting with the capture of Savanna, Georgia, in December 1778. As part of their strategy to take Charleston, they made an amphibious landing at Port Royal. The first attempt was turned back, but in the end the British occupied it and Beaufort from 1779 until 1781. During this time they looted and pillaged. After their defeat, many of the town’s Loyalists were fined or had their property confiscated, driving them out.

Coastal plantations resumed growing rice that generated vast wealth. Henry Middleton, for example, owned three plantations. When he died in 1846, his land was worth $77,000 and the rice grown there sold for $95,608. In 2022’s dollars, the combination of the two would be worth $6,480,847. The families who owned plantations didn’t stay on them during the hot Carolinian summers. Many moved to summer homes in Beaufort, May River and Bluffton. It was they who founded Beaufort College in 1795 and the Beaufort Library Society in 1807.

Their wealth was generated off the backs of slaves and the rice growing skills they brought with them from West Africa. Make no mistake that had plantation owners paid their workers fair wages, they’d still have become filthy rich. But greed is a funny thing and getting every last penny out of an investment is just too tempting for most.

Remember all those Loyalists forced to flee at the end of the Revolution? Many had headed to the Bahamas where they learned about long-staple cotton. Hard on soil, by the 1790s it could no longer be grown there, so many Loyalists returned home to their abandoned sea island plantations to cultivate it. The trouble was it was very labor intensive, fueling the need for more slaves, vastly expanding their numbers. On the island of St. Helena, for example, the slave population increased by 85.5 percent between 1800 and 1810. The number of plantations in the Beaufort area amounted to 881, seventy-nine of them having more than 100 slaves. On a typical sea island cotton plantation, slaves were given tasks each day that they were expected to fulfill, such as sorting 150 pounds of cotton or ginning 20 pounds of it. The descendants of these slaves are known as the Gullah Geechee

Coastal plantations resumed growing rice that generated vast wealth. Henry Middleton, for example, owned three plantations. When he died in 1846, his land was worth $77,000 and the rice grown there sold for $95,608. In 2022’s dollars, the combination of the two would be worth $6,480,847. The families who owned plantations didn’t stay on them during the hot Carolinian summers. Many moved to summer homes in Beaufort, May River and Bluffton. It was they who founded Beaufort College in 1795 and the Beaufort Library Society in 1807.

Their wealth was generated off the backs of slaves and the rice growing skills they brought with them from West Africa. Make no mistake that had plantation owners paid their workers fair wages, they’d still have become filthy rich. But greed is a funny thing and getting every last penny out of an investment is just too tempting for most.

Remember all those Loyalists forced to flee at the end of the Revolution? Many had headed to the Bahamas where they learned about long-staple cotton. Hard on soil, by the 1790s it could no longer be grown there, so many Loyalists returned home to their abandoned sea island plantations to cultivate it. The trouble was it was very labor intensive, fueling the need for more slaves, vastly expanding their numbers. On the island of St. Helena, for example, the slave population increased by 85.5 percent between 1800 and 1810. The number of plantations in the Beaufort area amounted to 881, seventy-nine of them having more than 100 slaves. On a typical sea island cotton plantation, slaves were given tasks each day that they were expected to fulfill, such as sorting 150 pounds of cotton or ginning 20 pounds of it. The descendants of these slaves are known as the Gullah Geechee

It’s small wonder South Carolina was the first state secede from the Union after Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860. Those who controlled its government had too much invested in slavery to risk Lincoln doing anything to threaten that. Beaufort was the birthplace of South Carolina’s secession led by resident Robert Barnwell Rhett.

That the seed of secession started in Beaufort didn’t go unnoticed in the North. Just six months after the outbreak of the Civil War, Union forces occupied and made it an administrative center. A hospital was established on nearby Hilton Head Island. It’s because the Union used the city’s grand houses for their own purposes that they weren’t burned down like so many others in the state.

Another effect of the Union occupation was it freed the thousands of slaves who hadn’t followed their masters to Confederate-controlled areas. In May 1862, General David Hunter decided to recruit former slaves as soldiers. Trained and armed on Hilton Head, they were put under the command of Colonel Thomas W. Higginson. At this stage in the war, blacks weren’t officially allowed to be part of the Union Army, but they nonetheless participated in raids into Georgia and Florida. They were officially made part of the Union Army on January 1, 1863, as the 1st South Carolina, which was later renamed the 33rd United States Colored Troops.

That the seed of secession started in Beaufort didn’t go unnoticed in the North. Just six months after the outbreak of the Civil War, Union forces occupied and made it an administrative center. A hospital was established on nearby Hilton Head Island. It’s because the Union used the city’s grand houses for their own purposes that they weren’t burned down like so many others in the state.

Another effect of the Union occupation was it freed the thousands of slaves who hadn’t followed their masters to Confederate-controlled areas. In May 1862, General David Hunter decided to recruit former slaves as soldiers. Trained and armed on Hilton Head, they were put under the command of Colonel Thomas W. Higginson. At this stage in the war, blacks weren’t officially allowed to be part of the Union Army, but they nonetheless participated in raids into Georgia and Florida. They were officially made part of the Union Army on January 1, 1863, as the 1st South Carolina, which was later renamed the 33rd United States Colored Troops.

The military only absorbed a fraction of the slaves freed when the Union overtook the region. In 1862, General Ormsby M. Mitchell, the officer in charge of Hilton Head Island, decided to set aside a place on Fish Haul Plantation to allow the newly freed slaves to establish a town. Called Mitchelville, its residents built houses and formed a government.

In 1862, money from the Union and supplies from relief agencies poured into Port Royal area. According to a museum information sign, “Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, General Rufus Saxton, and treasury agent Edward L. Pierce developed and operated a program to help former slaves become self-sufficient citizens. The Treasury Department and relief organizations provided food, clothing, and medical assistance.” In Beaufort, schools for former slaves were established by missionaries. The Union foreclosed on about 60,000 acres of land for tax delinquency and sold almost half of it to freedmen.

Out of the ashes of the Civil War rose the so-called New South where former slaves became full citizens and had a share in controlling the government. Beaufort County elected six African American state senators and twenty-four state legislators, one of whom was Robert Smalls. He served in South Carolina’s house from 1868 to 1870, and in its senate between 1870 and 1875.

In 1862, money from the Union and supplies from relief agencies poured into Port Royal area. According to a museum information sign, “Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, General Rufus Saxton, and treasury agent Edward L. Pierce developed and operated a program to help former slaves become self-sufficient citizens. The Treasury Department and relief organizations provided food, clothing, and medical assistance.” In Beaufort, schools for former slaves were established by missionaries. The Union foreclosed on about 60,000 acres of land for tax delinquency and sold almost half of it to freedmen.

Out of the ashes of the Civil War rose the so-called New South where former slaves became full citizens and had a share in controlling the government. Beaufort County elected six African American state senators and twenty-four state legislators, one of whom was Robert Smalls. He served in South Carolina’s house from 1868 to 1870, and in its senate between 1870 and 1875.

During the first year of the Civil War, Smalls was a pilot on the Confederate vessel CSS Planter. While docked in Charleston Harbor, her white crew disembarked for shore leave. Smalls and other slaves on board unmoored and sailed her straight to the Union blockade. As the Planter sailed past Fort Sumter, Smalls knew what the correct signal was to pass. In addition to arms and artillery, also on board was a code book, intelligence that the Confederates had abandoned their forts at the mouth of the Stono River, and a map showing the location of Confederate torpedoes and mines. Smalls and his crew were rewarded with $1,500 each in prize money.

South Carolinian integration and equality for its Black population ended when white supremacists led by Ben Tillman took over the government in 1890, spearheading the rewriting of the state constitution that resulted in the introduction of Jim Crow laws. Life in Beaufort County became downright awful starting in 1893 when a storm surge caused by a hurricane in late August killed at least 3,000 people, most of them African American. Next came the devastating fire of 1907 in Beaufort itself. Cotton prices dropped, then came boll weevil, which ended the growing of that cash crop in the area completely. During the Great Depression, Beaufort was one of the most impoverished places in the United States.

America’s entry into World War II was a turning point in its fortunes because of the influx of men going to Parris Island to train as Marines as well as the establishment of the nearby U.S. Naval Air Station in 1943 and the founding of a naval hospital in 1949. The heavy military presence helped ease the area into racial integration when the U.S. military was desegrated in 1948. School integration came in the 1960s as Jim Crow laws entered the dustbin of history. Martin Luther King, Jr. and members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference often came to St. Helena Island’s Penn Center to strategize. King wrote several of his speeches there. After his death in 1968, Beaufort County introduced a school holiday on the day of his funeral at the recommendation of the Community Relations Council.🕜

South Carolinian integration and equality for its Black population ended when white supremacists led by Ben Tillman took over the government in 1890, spearheading the rewriting of the state constitution that resulted in the introduction of Jim Crow laws. Life in Beaufort County became downright awful starting in 1893 when a storm surge caused by a hurricane in late August killed at least 3,000 people, most of them African American. Next came the devastating fire of 1907 in Beaufort itself. Cotton prices dropped, then came boll weevil, which ended the growing of that cash crop in the area completely. During the Great Depression, Beaufort was one of the most impoverished places in the United States.

America’s entry into World War II was a turning point in its fortunes because of the influx of men going to Parris Island to train as Marines as well as the establishment of the nearby U.S. Naval Air Station in 1943 and the founding of a naval hospital in 1949. The heavy military presence helped ease the area into racial integration when the U.S. military was desegrated in 1948. School integration came in the 1960s as Jim Crow laws entered the dustbin of history. Martin Luther King, Jr. and members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference often came to St. Helena Island’s Penn Center to strategize. King wrote several of his speeches there. After his death in 1968, Beaufort County introduced a school holiday on the day of his funeral at the recommendation of the Community Relations Council.🕜

Inside the Museum

Cannon

Cannon Balls

Ceramic Jar

Revolutionary War Costume on Creepy Manikin

South Carolinian Confederate Flag

Loop Sugar Masher

Beaufort History Museum