Berkeley County Museum & Heritage Center

These two doctors' buggies greet

visitors when they enter the museum.

visitors when they enter the museum.

Berkeley County Museum & Heritage Center

Little David Torpedo

Little David Replica

Located on the grounds of the Old Santee Canal Park in Moncks Corner, South Carolina, the Berkeley County Museum and Heritage Center opened in 1992 and is so jam-packed with displays and information that covering everything in it would involve writing a rather long book. Fortunately my travel logs are just a highlight of what I found with the goal of prompting others to visit. If you happen to be in Charleston to the south of here like I was, it’s well worth the fifty minute or so drive to get here.

The museum is housed in a colonial-style Low County house (whatever that is) of the sort found in this area. As my traveling companions and I approached, we saw setting outside some sort of boat of a type I couldn’t readily identify. At first I thought it was a submarine, perhaps one that was contemporary with the famous CSS Hunley. The vessel in question turned out not to be a true submersible but rather something quite unique. She sailed low the sea, her deck about a foot above the water. And unlike the Hunley, she was steam-powered. Protruding from her bow was a long spar tipped with a torpedo.

This particular boat was christened the David and built at Moncks Corners. She was constructed to sink ships blockading Charleston Harbor to the south. Her first target was the iron-clad Union vessel New Ironsides. On the evening of October 5, 1863, the David, under the command of Lieutenant W.T. Glassell, steamed towards her goal. The David’s crew consisted of three volunteers: assistant Engineer James H. Toombs, who tended to the machinery and attached the torpedo, Walker Cannon, the pilot, and James Sullivan, the fireman. Around nine that night the David struck, hitting the New Ironsides under her waterline on her starboard quarter near the stern. The explosion caused a fountain of water to erupt from the sea that swamped the David, putting her boiler fire out and incapacitating her engine.

Unable to navigate, she drifted under New Ironsides’ bow. Taking small arms fire from the New Ironside’s crew and certain the David would sink, all but Cannon abandoned ship. Sullivan and Glassell were ultimately captured. Toombs returned to the vessel and effected repairs, allowing he and Cannon to sail back to Charleston. The David made two more known attacks before she disappeared in the mists of history. The New Ironsides suffered so much damage she retired to a Philadelphia drydock and was ultimately burned. The David one sees outside the museum is a replica that, according to a plaque, “was originally constructed as an historical exhibit in 1970 by students and staff at Trident Technical College in North Charleston in preparation for South Carolina’s tricentennial observance.” (An excellent and more detailed history of the original David can be found here.)

This particular boat was christened the David and built at Moncks Corners. She was constructed to sink ships blockading Charleston Harbor to the south. Her first target was the iron-clad Union vessel New Ironsides. On the evening of October 5, 1863, the David, under the command of Lieutenant W.T. Glassell, steamed towards her goal. The David’s crew consisted of three volunteers: assistant Engineer James H. Toombs, who tended to the machinery and attached the torpedo, Walker Cannon, the pilot, and James Sullivan, the fireman. Around nine that night the David struck, hitting the New Ironsides under her waterline on her starboard quarter near the stern. The explosion caused a fountain of water to erupt from the sea that swamped the David, putting her boiler fire out and incapacitating her engine.

Unable to navigate, she drifted under New Ironsides’ bow. Taking small arms fire from the New Ironside’s crew and certain the David would sink, all but Cannon abandoned ship. Sullivan and Glassell were ultimately captured. Toombs returned to the vessel and effected repairs, allowing he and Cannon to sail back to Charleston. The David made two more known attacks before she disappeared in the mists of history. The New Ironsides suffered so much damage she retired to a Philadelphia drydock and was ultimately burned. The David one sees outside the museum is a replica that, according to a plaque, “was originally constructed as an historical exhibit in 1970 by students and staff at Trident Technical College in North Charleston in preparation for South Carolina’s tricentennial observance.” (An excellent and more detailed history of the original David can be found here.)

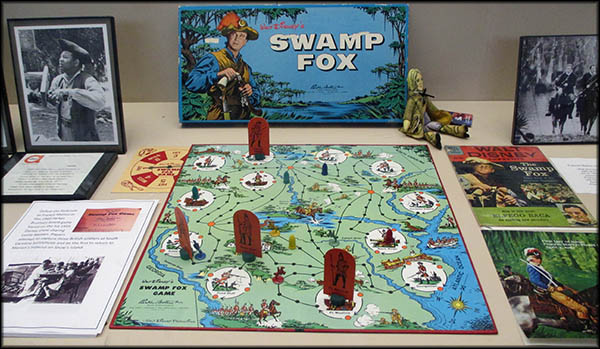

In addition to being the David’s place of construction, Berkeley County also produced Revolutionary war hero Francis Marion, known as the Swamp Fox. Descended from French Huguenots and born in 1732, he was the youngest of six children. For his first twelve years he was, according to American National Biography, “a frail and puny lad.” After this “he grew stronger” and by the age of sixteen joined the crew of a schooner headed for the West Indies. Struck by a whale, she sunk, forcing the crew to retreat to a jolly boat. Here they remained for a week until a passing ship saved them. By then two of the crew had died.

Cashing in on Francis Marion

Returning home and never again going to sea, Marion joined a colonial militia in 1756. In 1761, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel James Grant of the British Army, he participated in a campaign against the Cherokee. During the War of Independence, he joined the Continental Army as an officer.

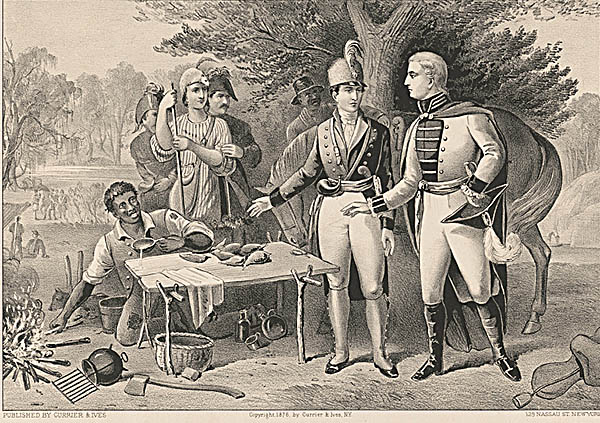

"General Francis Marion, of South Carolina."

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

In 1780 he suffered a serious injury—folklore says he jumped out of a window at John Stuart’s Charleston house to escape an insufferable party, breaking his leg—but by July 1780 he was back in action. Assigned to General Johann Kalb’s army in North Carolina, Marion was sent on a reconnaissance mission. When he returned to the main force, General Horatio Gates had taken charg. Soon enough Gates’ army was routed by British general Lord Charles Cornwallis. Fortunately for Marion, before that occurred, he’d been put in charge of a detachment sent south to severe British lines of communications with Charleston. Not long after Gates’ defeat, American general Thomas Sumpter was soundly thumped by the British at the Battle of Catawba Ford in South Carolina, eliminating any significant American military presence in the South.

Marion, promoted to brigadier general, was made head of a militia tasked with harassing the British. His force never amounted to more than two hundred men and was usually no more than just a few dozen. He became a master of guerrilla warfare, a tactic he used out of necessity. One of the many legends about him, one probably invented by that notorious writer of fiction in the guise of biography, Parson Weems, was that while in the swamp, Marion served sweet potatoes to a visiting British officer. During the meal Marion boasted his pride that he and his men weren’t paid. According to Weems, Marion’s dinner guest later remarked to his superior: “I have seen an American general and his officers, without pay, and almost without clothes, living on roots and drinking water; and all for Liberty! What chance have we against such men!” Rousing stuff and it was true enough that Marion and his men lacked supplies, lived off simple fare, and rarely if ever received pay. Marion earned the name “Swamp Fox” because of his ability to disappear into the swamps and his effectiveness of causing the British Army much pain and suffering.

But all was not rosy. Marion was constantly frustrated that his men came and went at will. Also, not all his men served willingly. Some were slaves and didn’t have a choice in whether or not they fought. Marion himself had with him a slave owned by his parents named Oscar Marion. Oscar was born on Goatfield Plantation along the Cooper River. Throughout the war he served with Francis, probably as a servant, though he likely as not did some fighting when the need arose. So was Francis grateful for Oscar’s service? He was not. When he died on February 26, 1795, he didn’t bother to free Oscar or any of his other seventy-three slaves. President George W. Bush and Representative Albert Wynn officially honored Oscar Marion on December 15, 2006.

But all was not rosy. Marion was constantly frustrated that his men came and went at will. Also, not all his men served willingly. Some were slaves and didn’t have a choice in whether or not they fought. Marion himself had with him a slave owned by his parents named Oscar Marion. Oscar was born on Goatfield Plantation along the Cooper River. Throughout the war he served with Francis, probably as a servant, though he likely as not did some fighting when the need arose. So was Francis grateful for Oscar’s service? He was not. When he died on February 26, 1795, he didn’t bother to free Oscar or any of his other seventy-three slaves. President George W. Bush and Representative Albert Wynn officially honored Oscar Marion on December 15, 2006.

The museum also has a display about Francis Marion’s wife, Mary Ester Videau. She married Francis on April 20, 1786, a boon for him because the war had ruined him financially and her fortune allowed him to forgo working for a living as he had been doing. Mary, born on September 17, 1737, was a native of Berkeley County and she, too, was of French descent (which is pretty obvious considering her maiden name). Francis was her cousin and, after the war, neighbor. It was her nephew, Theodore Marion, who suggested Francis call upon her. Because Mary was forty-eight when she and Francis married, it ought not come as a surprise the couple had no children. Instead they adopted their nephew, Francis Marion Dwight, as their heir. Mary died on July 26, 1815.

One of Francis Marion’s contemporaries and fellow plantation owners was Berkeley County’s Henry Laurens. He served as president of the Continental Congress in 1777 and 1778, and in September 1780 while sailing to the Netherlands he was captured by the British. Taken to England, he became, according to a museum information sign, “the only American held in the Tower of London during the American Revolution.” He was exchanged for no less a British prisoner than Lord Cornwallis himself. Despite being a supposed proponent of liberty, Laurens had made much of his fortune with his slave trading firm Austin & Laurens. As if human bondage weren’t bad enough, slave traders broke up about one in five marriages and separated from their parents fifty percent of children fourteen and under. In addition to slave trading, Laurens also owned over 300 slaves to work his rice planation. In 1790 Berkley County had 103,000 slaves, far larger than the white population of 30,0070.

One of Francis Marion’s contemporaries and fellow plantation owners was Berkeley County’s Henry Laurens. He served as president of the Continental Congress in 1777 and 1778, and in September 1780 while sailing to the Netherlands he was captured by the British. Taken to England, he became, according to a museum information sign, “the only American held in the Tower of London during the American Revolution.” He was exchanged for no less a British prisoner than Lord Cornwallis himself. Despite being a supposed proponent of liberty, Laurens had made much of his fortune with his slave trading firm Austin & Laurens. As if human bondage weren’t bad enough, slave traders broke up about one in five marriages and separated from their parents fifty percent of children fourteen and under. In addition to slave trading, Laurens also owned over 300 slaves to work his rice planation. In 1790 Berkley County had 103,000 slaves, far larger than the white population of 30,0070.

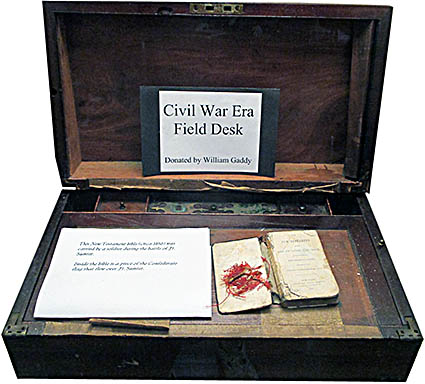

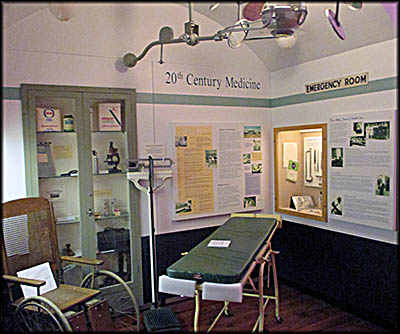

Berkeley County prospered until South Carolina’s secession sparked the Civil War and ended slavery for good. By the turn of the century the vast majority of those living here were impoverished. Despite the fact the county comprises over 12,000 square miles, it had just a few traveling doctors who used buggies, rode on horseback, or took boats to get around. According to an information sign in the museum’s 20th Century Medicine exhibit, “the mortality rate was high due to the ravages of malaria and communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, venereal disease, diphtheria, whooping cough, typhoid fever, smallpox, polio and more. In 1930, the county’s infant mortality rate was 13.3 percent. Many women died giving birth, deformities were common and birth control was unknown.”

In 1928 and 1929, the executive secretary Berkeley County’s Tuberculosis Association, Anne Sinkler Fishburne, started a fundraiser to create a sanatorium for sufferers of that disease. This mostly small donation effort raised $8,000. South Carolina’s General Assembly passed a bill giving the county permission to buy land for it, pay to construct a building upon it, then equip the sanatorium. It would be paid for in part by a $10,000 bond issue. Needing still more money, the Duke Endowment was asked if it would donate some funds. Maybe. It only gave to general care facilities and required a minimum of $35,000 be raised before it would handed out matching money.

To meet these requirements, the sanatorium would instead become a general medical hospital with a tuberculosis wing. New York businessman Hugh Robertson, who owned and ran Richland Planation in Berkeley County, gave $72,000 to the project, prompting the Duke Endowment to donate $55,000. Robertson wanted the hospital because the workers on his planation sorely needed it. The hospital officially opened on January 15, 1933. State-of-the-art when built, by the 1970s it become obsolete and in 1975 it closed.

In 1928 and 1929, the executive secretary Berkeley County’s Tuberculosis Association, Anne Sinkler Fishburne, started a fundraiser to create a sanatorium for sufferers of that disease. This mostly small donation effort raised $8,000. South Carolina’s General Assembly passed a bill giving the county permission to buy land for it, pay to construct a building upon it, then equip the sanatorium. It would be paid for in part by a $10,000 bond issue. Needing still more money, the Duke Endowment was asked if it would donate some funds. Maybe. It only gave to general care facilities and required a minimum of $35,000 be raised before it would handed out matching money.

To meet these requirements, the sanatorium would instead become a general medical hospital with a tuberculosis wing. New York businessman Hugh Robertson, who owned and ran Richland Planation in Berkeley County, gave $72,000 to the project, prompting the Duke Endowment to donate $55,000. Robertson wanted the hospital because the workers on his planation sorely needed it. The hospital officially opened on January 15, 1933. State-of-the-art when built, by the 1970s it become obsolete and in 1975 it closed.

Although the county suffered from poverty at the turn of the twentieth century, in 1900 a number of lumbering companies, including the Burton Lumber Company, began operations here. This was good in the short term but not so much for the long one. By the time of the stock market crash in 1929, which marked the beginning of the Great Depression, much of Berkeley County had been deforested, its streams, according to an information sign, “clogged with tree limbs and debris.”

Enter President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. One of the government programs to get Americans back to work was the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC). Its main job was to restore deforested lands. In 1936 FDR ordered the Forest Service to purchase the region’s unwanted land, which many land owners gladly sold to rid themselves of it. Others had lost their land because they couldn’t pay their property taxes. This new government land was designated the Francis Marion National Forest. The CCC planted new trees, restored soil, and put in roads. When Hurricane Hugo swept through the region in 1989, it felled all but the youngest trees, so what you see today mostly grew after that year.

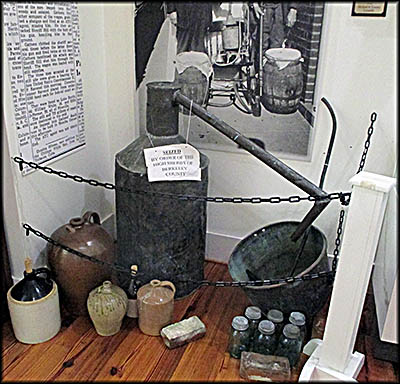

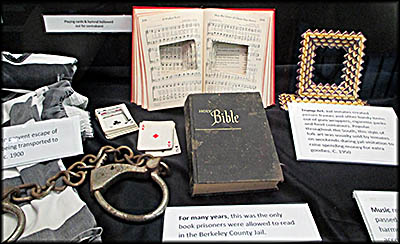

Despite the ravaged state of Berkeley County’s forests and swamps, in the 1920s they provided the perfect place for corn-based illegal distilleries to operate. The county soon became known as South Carolina’s “Moonshine Capitol.” Bootleggers became infamous for creating hot rods that could outrun the police. The Berkeley County Sherriff’s Department spent much of its time and energy trying to deal with these bandits and to stop bootlegging in general. The sheriff’s department was also responsible for overseeing the Berkeley County Jail. Many interesting artifacts from it are on display, including a gun made out of soap, a book with its center removed so contraband could be smuggled in it, a ball and chain used for road gangs, and cards and dice prisoners used despite the fact gambling was forbidden.🕜

Enter President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. One of the government programs to get Americans back to work was the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC). Its main job was to restore deforested lands. In 1936 FDR ordered the Forest Service to purchase the region’s unwanted land, which many land owners gladly sold to rid themselves of it. Others had lost their land because they couldn’t pay their property taxes. This new government land was designated the Francis Marion National Forest. The CCC planted new trees, restored soil, and put in roads. When Hurricane Hugo swept through the region in 1989, it felled all but the youngest trees, so what you see today mostly grew after that year.

Despite the ravaged state of Berkeley County’s forests and swamps, in the 1920s they provided the perfect place for corn-based illegal distilleries to operate. The county soon became known as South Carolina’s “Moonshine Capitol.” Bootleggers became infamous for creating hot rods that could outrun the police. The Berkeley County Sherriff’s Department spent much of its time and energy trying to deal with these bandits and to stop bootlegging in general. The sheriff’s department was also responsible for overseeing the Berkeley County Jail. Many interesting artifacts from it are on display, including a gun made out of soap, a book with its center removed so contraband could be smuggled in it, a ball and chain used for road gangs, and cards and dice prisoners used despite the fact gambling was forbidden.🕜

Revolutionary War Exhibit

Francis Marion, the "Swamp Fox"

Marion Esther Videau Marion Display

Civil War Era Field Desk

Shack

Guano Distributer

20th Century Medicine Exhibit

Items Seized by the Berkeley

County Sherriff's Department

County Sherriff's Department

Artifacts from the Berkeley County Jail