Canaday Center for Special Collections

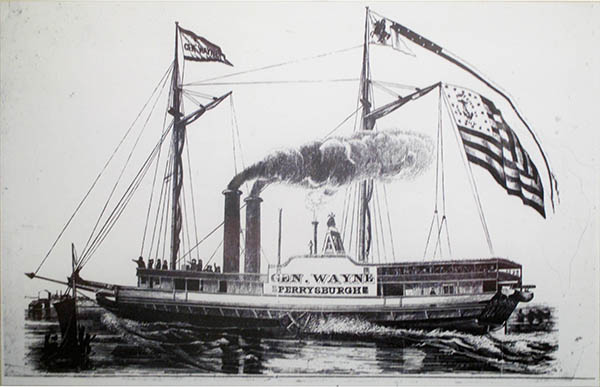

The Anthony Wayne, which was built in Toledo, sank near Vermilion, Ohio, on April 28, 1850.

Exhibit Room

G.P. Griffith

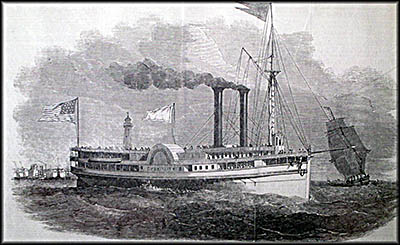

Early steamboats on the Great Lakes were inefficient and often ran out of fuel, so they had to also have sail power.

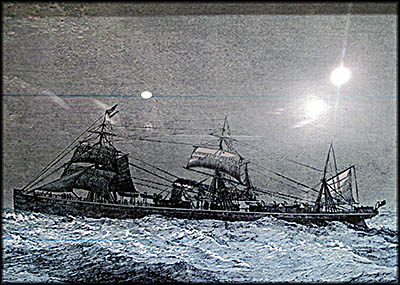

SS. Edmund Fitzgerald

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Ste. Claire

Railroad Depot in Bowling Green, Ohio, c. 1900

Nickel Plate Railroad Timetables and Maps

Toledo Middlegrounds

Railroad Signal Book

This collection of canal songs was compiled in 1952.

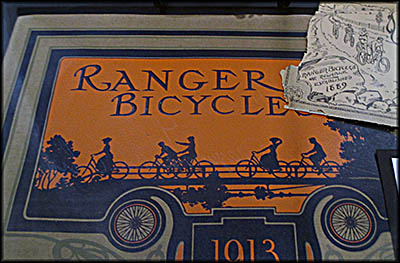

A bicycle craze in the 1890s preceded the dawn of the automobile.

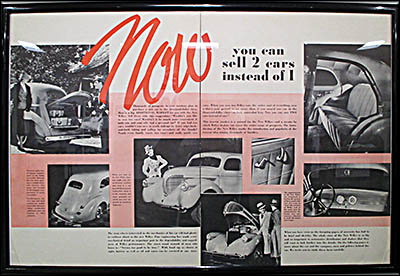

Willys-Overland Ads

This driving light was made by Normal Thal, Sr., and was the predecessor of the headlight.

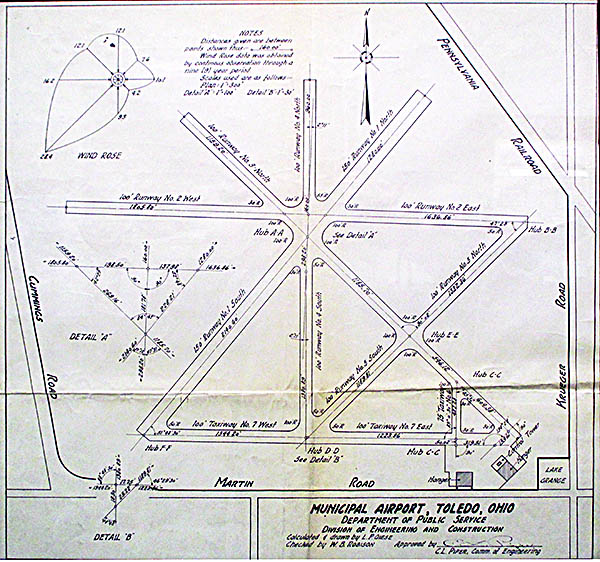

Map of Toledo Municipal Airport

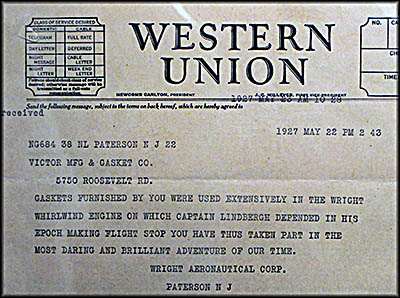

The telegram reports that Charles Lindberg successfully completed his solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean.

A travel log about a special collections department at the University of Toledo’s Carlson Library might seem a bit odd considering that I usually write about historic places or history museums, but bear with me. I went to William M. Canaday Center for Special Collections to examine documents from the Willys-Overland Auto Company in the hope it would contribute to my research on this topic (it didn’t). While there, I unexpectedly came across the “Arrivals and Departures: A History of Transportation in Toledo and Northwest Ohio” exhibit.

This single-room exhibit is jam-packed with artifacts and well-done information signs. Complementing it is a free, full-color companion catalog that includes the verbiage from the information signs plus a whole lot more content. The exhibit starts with canals and rivers. With a good swath of northwest Ohio being covered with the Great Black Swamp, traveling overland wasn’t very efficient and sometimes not possible for a land-based vehicle. Native Americans and early European settlers used Ohio’s extensive river system to get around.

This single-room exhibit is jam-packed with artifacts and well-done information signs. Complementing it is a free, full-color companion catalog that includes the verbiage from the information signs plus a whole lot more content. The exhibit starts with canals and rivers. With a good swath of northwest Ohio being covered with the Great Black Swamp, traveling overland wasn’t very efficient and sometimes not possible for a land-based vehicle. Native Americans and early European settlers used Ohio’s extensive river system to get around.

Canoes are fine for personal travel, but if you want transport large amounts of cargo, what you really need are flatboats and, later, steamboats. The trouble is that while Ohio does have some deep rivers, most of those in its interior aren’t navigable enough for this purpose. The solution was canals. Ohio dug two major ones connecting Lake Erie to the Ohio River: the Ohio & Erie for the eastern part of the state and the Miami & Erie for the western half. The latter stretched from Toledo to Cincinnati. Aside from the commercial opportunities this brought, it also attracted settlers. The catalog says that between 1840 and 1850, the population of northwest Ohio increased by an impressive eighty percent. It failed to mention this was at the expense of the Native American population, who were forced out.

The largest city in northwest Ohio is Toledo. Founded in 1833, it was originally incorporated in the Michigan Territory, but after the conclusion of the so-called Toledo War, it reincorporated as an Ohio municipality in 1837. That it started along the mouth of the Maumee River was no accident. The river was (and is) deep enough here to accommodate large vessels coming in from Lake Erie, and its navigable for smaller vessels for about another twelve miles southward. What couldn’t be transported down the river could be taken by the Miami & Erie Canal.

Toledo stands along Lake Erie, and it offered its own routes to other places. Although the first steamboat on the lake, the Walk-on-the-Water, appeared in 1818 (and sank three years later), it took decades for steam to completely usurp sail power. One reason for this lengthy transition was the slow technological evolution of the steam engine. In its earliest days, it was fine for boats on rivers, but sailing on an inland sea like Lake Erie with steam power is far more challenging. Early steam engines weren’t efficient and required massive amount of fuel to maintain power, so they often had sails in case the fuel ran out. This “solution” caused another problem: the masts, sails and rigging made such vessels top heavy and thus prone to rolling over in rough seas.

Although the notoriously rough seas of Lake Erie have sent many a vessel to the bottom, steam-powered vessels had little problem sinking themselves. The steamer Anthony Wayne, built along the Maumee River in Perrysburg, went down on April 28, 1850, near Vermilion, Ohio, when one of her boilers exploded. She wasn’t discovered until 2007 and is now, according to an information sign, “the only shipwreck in Ohio on the National Register of Historic Places.”

The largest city in northwest Ohio is Toledo. Founded in 1833, it was originally incorporated in the Michigan Territory, but after the conclusion of the so-called Toledo War, it reincorporated as an Ohio municipality in 1837. That it started along the mouth of the Maumee River was no accident. The river was (and is) deep enough here to accommodate large vessels coming in from Lake Erie, and its navigable for smaller vessels for about another twelve miles southward. What couldn’t be transported down the river could be taken by the Miami & Erie Canal.

Toledo stands along Lake Erie, and it offered its own routes to other places. Although the first steamboat on the lake, the Walk-on-the-Water, appeared in 1818 (and sank three years later), it took decades for steam to completely usurp sail power. One reason for this lengthy transition was the slow technological evolution of the steam engine. In its earliest days, it was fine for boats on rivers, but sailing on an inland sea like Lake Erie with steam power is far more challenging. Early steam engines weren’t efficient and required massive amount of fuel to maintain power, so they often had sails in case the fuel ran out. This “solution” caused another problem: the masts, sails and rigging made such vessels top heavy and thus prone to rolling over in rough seas.

Although the notoriously rough seas of Lake Erie have sent many a vessel to the bottom, steam-powered vessels had little problem sinking themselves. The steamer Anthony Wayne, built along the Maumee River in Perrysburg, went down on April 28, 1850, near Vermilion, Ohio, when one of her boilers exploded. She wasn’t discovered until 2007 and is now, according to an information sign, “the only shipwreck in Ohio on the National Register of Historic Places.”

Shortly after this incident on June 17, the G.P. Griffith, built in Maumee three years earlier, caught fire near what is today, Mentor. The captain tried to beach her, but she got caught on a sandbar before reaching the shore. Around 250 people lost their lives.

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which went down on Lake Superior and is possibly the most well-known shipwreck on the Great Lakes, had close ties to Toledo in more ways than one. One of her routes frequently took for from Lake Superior to Toledo, giving her the nickname the “Toledo Express.” When she sank on November 10, 1975, her captain, Ernest M. McSorely, and six of the crew (out of twenty-eight) were from Toledo or its suburbs. The exhibition lists seven crewmen as being from the Toledo area, but I don’t think Ralph Walton counts. An oiler, he was from Fremont, and that’s no more a part of the Toledo area than is Timbuktu.

For over 100 years, Toledo had a robust ship and boat building industry, the last one closing in 1985. Its yards produced the ferry Ste. Claire in 1910, a vessel that’s still afloat. After twenty-eight years of service taking passengers across the Detroit River for the Detroit & Windsor Ferry Company, she was purchased by the Boblo Island Amusement Park located on the island of Bois Blanc in Ontario. Starting in 1938, she and another ferry, Columbia, took passengers from Detroit to the island and back until 1993, the year the park closed. Usually, vessels as old as these two (Columbia was built in 1902) are sold for scrap or broken up after their usefulness ends, but in this case, nonprofits have taken possession and are in the process of restoring them.

It’s unlikely Toledo would’ve grown to its present size—its population peaked at 392,000 residents in 1965—had the railroads not connected to it. The first to do so was the Erie & Kalamazoo. Opened in 1836, it started with oak rails carrying cars pulled by horses. That’s not very efficient—not to mention that wooden rails would soon rot—so the road switched to iron rails and began using a steam locomotive for power. It was the first railroad built west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which went down on Lake Superior and is possibly the most well-known shipwreck on the Great Lakes, had close ties to Toledo in more ways than one. One of her routes frequently took for from Lake Superior to Toledo, giving her the nickname the “Toledo Express.” When she sank on November 10, 1975, her captain, Ernest M. McSorely, and six of the crew (out of twenty-eight) were from Toledo or its suburbs. The exhibition lists seven crewmen as being from the Toledo area, but I don’t think Ralph Walton counts. An oiler, he was from Fremont, and that’s no more a part of the Toledo area than is Timbuktu.

For over 100 years, Toledo had a robust ship and boat building industry, the last one closing in 1985. Its yards produced the ferry Ste. Claire in 1910, a vessel that’s still afloat. After twenty-eight years of service taking passengers across the Detroit River for the Detroit & Windsor Ferry Company, she was purchased by the Boblo Island Amusement Park located on the island of Bois Blanc in Ontario. Starting in 1938, she and another ferry, Columbia, took passengers from Detroit to the island and back until 1993, the year the park closed. Usually, vessels as old as these two (Columbia was built in 1902) are sold for scrap or broken up after their usefulness ends, but in this case, nonprofits have taken possession and are in the process of restoring them.

It’s unlikely Toledo would’ve grown to its present size—its population peaked at 392,000 residents in 1965—had the railroads not connected to it. The first to do so was the Erie & Kalamazoo. Opened in 1836, it started with oak rails carrying cars pulled by horses. That’s not very efficient—not to mention that wooden rails would soon rot—so the road switched to iron rails and began using a steam locomotive for power. It was the first railroad built west of the Appalachian Mountains.

One of the artifacts on display in the railroad section of the exhibit is a book of timetables and maps for the Nickel Plate Railroad. Incorporated as the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railroad, its nickname came from an article that appeared in the Norwalk Chronicle describing it as a “double track, nickel-plated railroad.” Some sources say “nickel-plated” referred to the mass of money it was supposed to make. Others that it referenced its profitability. In any case, its tracks were ordinary and not covered in nickel.

The road went through Fort Wayne, Indiana, and had a major yard in Bellevue, Ohio, and here it has a personal connection to my family’s history. My grandfather, John Stein Sr., worked for the Nickel Plate in Fort Wayne, then transferred to the Bellevue yards, and to this day that side of my family lives in the area. During my grandfather’s time there, the Nickel Plate became part of Norfolk & Western, which is now Norfolk & Southern. It was the last major railroad to switch from steam to diesel.

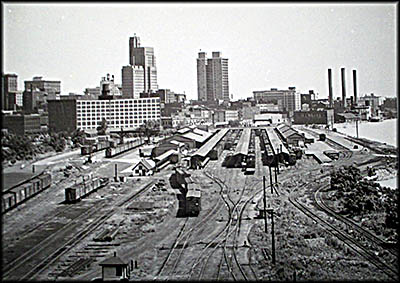

Toledo became a railroad mecha. When it opened its New Central Union Terminal in 1950, no less than seventeen railroads came into the city. Yet this was a moment of decline for northwest America’s railroads, a trend that started in 1920s and hit a crisis point in 1969 when passenger service was unavailable in many locations. The solution to that problem was AMTRAK. Today it’s the only passenger rail service that comes to Toledo, and only five freight roads go through the city.

The road went through Fort Wayne, Indiana, and had a major yard in Bellevue, Ohio, and here it has a personal connection to my family’s history. My grandfather, John Stein Sr., worked for the Nickel Plate in Fort Wayne, then transferred to the Bellevue yards, and to this day that side of my family lives in the area. During my grandfather’s time there, the Nickel Plate became part of Norfolk & Western, which is now Norfolk & Southern. It was the last major railroad to switch from steam to diesel.

Toledo became a railroad mecha. When it opened its New Central Union Terminal in 1950, no less than seventeen railroads came into the city. Yet this was a moment of decline for northwest America’s railroads, a trend that started in 1920s and hit a crisis point in 1969 when passenger service was unavailable in many locations. The solution to that problem was AMTRAK. Today it’s the only passenger rail service that comes to Toledo, and only five freight roads go through the city.

Toledo and its suburbs cover a lot of ground, but today the only mass transit available you can only get around on are buses run by the Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority (TARTA). At one point Toledo was served by streetcars and a robust electric interurban service that could take riders far and wide. For longer trips, a person could take a passenger train, of which there were many. Streetcars declined and disappeared because they were unable to compete with the automobile and buses, and most streetcar companies went out of business by the 1930s. Today the only effective way to get around northwest Ohio is by car. Mass transit options are few and far between.

This makes a lot of sense considering Toledo became an important part of the auto industry, although none of its homegrown car makers lasted long. One car maker that originated in Indiana and made its home in Toledo was Willys-Overland. It was at one point Toledo’s biggest employer, and its plant was the largest one in the United States. Today few collectors clamor for most of its cars save for some whose bodies make for good drag racers.

There is a notable exception: the Jeep. Shortly before World War II, the U.S. Army wanted an all-purpose, durable vehicle it could use in a warzone, and asked for submissions. The struggling car maker Bantam was initially the only taker, and its prototype is what Willys-Overland based the Jeep on. Despite having a four-cylinder engine, this truck (it’s official classification at the time) so impressed those who used it, that its civilian version remains popular today. Willys-Overland merged with Kaiser Motors in 1953, at which point it became the Willys Motor Company. The Willys (pronounced Will-is) name went extinct in 1963 when the company changed it to Kaiser Jeep. These days the Jeep is owned by Stellantis. It’s still made in Toledo.

This makes a lot of sense considering Toledo became an important part of the auto industry, although none of its homegrown car makers lasted long. One car maker that originated in Indiana and made its home in Toledo was Willys-Overland. It was at one point Toledo’s biggest employer, and its plant was the largest one in the United States. Today few collectors clamor for most of its cars save for some whose bodies make for good drag racers.

There is a notable exception: the Jeep. Shortly before World War II, the U.S. Army wanted an all-purpose, durable vehicle it could use in a warzone, and asked for submissions. The struggling car maker Bantam was initially the only taker, and its prototype is what Willys-Overland based the Jeep on. Despite having a four-cylinder engine, this truck (it’s official classification at the time) so impressed those who used it, that its civilian version remains popular today. Willys-Overland merged with Kaiser Motors in 1953, at which point it became the Willys Motor Company. The Willys (pronounced Will-is) name went extinct in 1963 when the company changed it to Kaiser Jeep. These days the Jeep is owned by Stellantis. It’s still made in Toledo.

Toledo never got into the aircraft-making business, but it did realize that having an airport was an excellent idea. Its first, the Toledo Municipal Airport, opened in along Stickney Avenue in October 1927, but it lasted just eight months. Next came the Toledo Transcontinental Airport located in the village of Walbridge. It was, according to the exhibit catalog, “the second largest airport east of the Rockies,” but the Great Depression caused its closure. The city of Toledo bought it, then renamed it Toledo Municipal Airport, which became Metcalf Field in 1977 and Toledo Executive Airport in 2010.

It wasn’t big enough to accommodate the larger planes being built after World War II, so in 1950, the city of Toledo decided to construct an airport that could accommodate them. Without federal assistance, the city had to finance the project itself. Several industries donated land in the area chosen for the airport’s construction—Oak Openings in Monclova—and the city raised the money to build it by passing a $3.5 million levy. Dedicated on October 31, 1954, it opened as Toledo Express Airport. The next year carriers from the old airport moved their operations here. Although it still operates, it’s down to one commercial carrier (Allegiant) and these days its focus is serving freight carriers.

The “Arrivals and Departures” exhibit closes on December 11, 2025. If you want to visit, you’ll either need to use metered parking in Lot 11, or pay for a day pass using the campus’ website. I recommend metered parking. If you don’t want to pay, you’ll have to find an off-campus parking lot and walk over.🕜

It wasn’t big enough to accommodate the larger planes being built after World War II, so in 1950, the city of Toledo decided to construct an airport that could accommodate them. Without federal assistance, the city had to finance the project itself. Several industries donated land in the area chosen for the airport’s construction—Oak Openings in Monclova—and the city raised the money to build it by passing a $3.5 million levy. Dedicated on October 31, 1954, it opened as Toledo Express Airport. The next year carriers from the old airport moved their operations here. Although it still operates, it’s down to one commercial carrier (Allegiant) and these days its focus is serving freight carriers.

The “Arrivals and Departures” exhibit closes on December 11, 2025. If you want to visit, you’ll either need to use metered parking in Lot 11, or pay for a day pass using the campus’ website. I recommend metered parking. If you don’t want to pay, you’ll have to find an off-campus parking lot and walk over.🕜