Castle Museum of Saginaw County History

Castle Museum of Saginaw County History

This Carousel miniature was carved by Ronald E. Fahrner in the early 1990s. It was on display in the museum's main hall.

This terracotta lion's head once decorated the Saginaw Daily News Building.

Part of the exhibit outlining the history of the Castle Museum in its days as a post office.

Postal inspectors used this tunnel to secretly watch workers below.

Reproduction of a Native American Shelter

Beaver fur was in high demand in Europe for several centuries because it made such warm hats.

Log from an old growth tree.

Lumberjack Bunk

Huckster Wagon

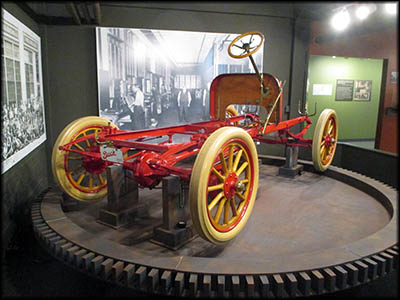

Buick chassis were once made in Saginaw.

Exhibit about some of Saginaw's businesses.

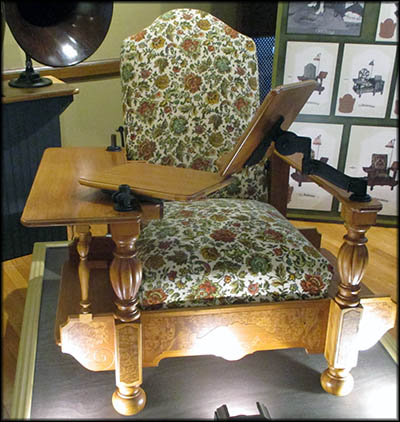

Furniture Exhibit

Bricks made by the Saginaw Paving Brick Company

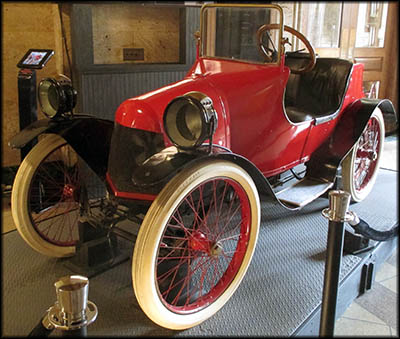

Saginaw Cyclecar made by the Valley Boat and Engine Company made between 1914 and 1919.

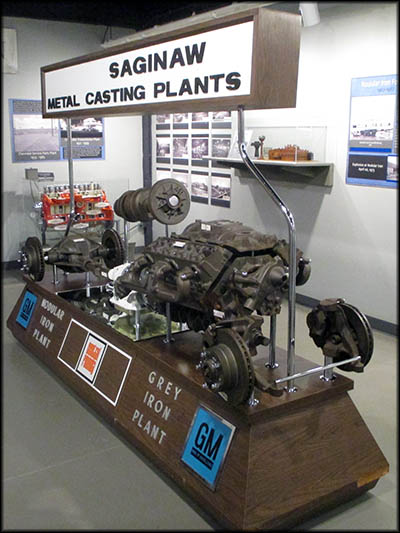

Items made by the Saginaw Casting Plants

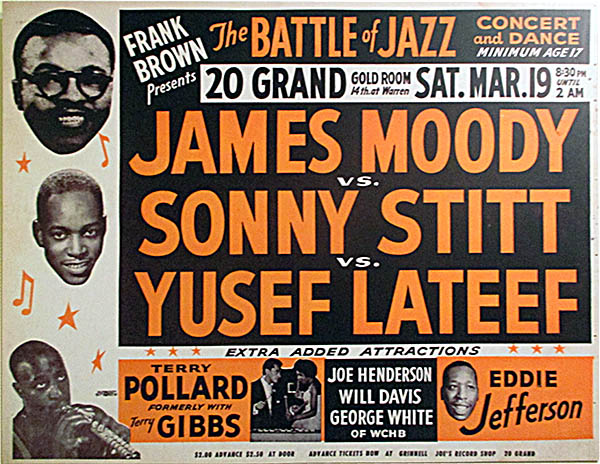

Poster advertising a concert featuring Sonny Stitt, a jazz saxophonist who was raised in Saginaw.

Eskwin Chair

For a nation that never needed them as means of defense, the United States sure has a good number of castles. In Michigan alone, as an example, there are at least eighteen of them, one of which stands in downtown Saginaw. Now known as the Castle Museum of Saginaw County History, it was originally the city’s post office. In 1889, Saginaw Congressman Aaron Bliss, who later became Michigan’s governor, lobbied Congress to appropriate $100,000 for it, a project that had been in planning since at least 1893.

The hardest part wasn’t getting the funds for construction but rather agreeing on a design. The first two were rejected, and it wasn’t until 1887 that the third, final one, was accepted. It was created by William M. Aiken, the Treasury Department’s supervising architect. He decided to honor Saginaw’s French roots by making the new post office look like a French chateau—at least on the exterior. Construction began on May 11, 1897, and it opened on July 3, 1898.

By the 1930s, it was insufficient to serve Saginaw and a replacement was planned. Federal bureaucrats aren’t known for their appreciation of architecture, which probably explains their desire to tear down the existing building and replace it with a new one. Fortunately community opposition compelled a change in plan, so in 1937 it was instead remodeled. Additions were made and some sections, such as the tower facing South Jefferson Avenue, were removed. The interior was reconfigured, and a new lobby replaced the old one.

The hardest part wasn’t getting the funds for construction but rather agreeing on a design. The first two were rejected, and it wasn’t until 1887 that the third, final one, was accepted. It was created by William M. Aiken, the Treasury Department’s supervising architect. He decided to honor Saginaw’s French roots by making the new post office look like a French chateau—at least on the exterior. Construction began on May 11, 1897, and it opened on July 3, 1898.

By the 1930s, it was insufficient to serve Saginaw and a replacement was planned. Federal bureaucrats aren’t known for their appreciation of architecture, which probably explains their desire to tear down the existing building and replace it with a new one. Fortunately community opposition compelled a change in plan, so in 1937 it was instead remodeled. Additions were made and some sections, such as the tower facing South Jefferson Avenue, were removed. The interior was reconfigured, and a new lobby replaced the old one.

One of the biggest reasons the French began exploring what is today Michigan was to expand its fur trading empire. The French never attempted to colonize all of Michigan, although they did found Detroit as a fur trading post and build forts to keep the British out. The existence of the latter helped cause the French and Indian War (itself part of the larger Seven Years War), a conflict the French lost. In the peace settlement, France handed Canada over to the British, territory that included Michigan, which then came into the hands of the United States upon its triumph over Britain in the American Revolution.

It’s at this point things went bad for the native people living here. Americans were land hungry and wanted to move in permanently. During the War of 1812 the majority of Michigan’s and Ohio’s native peoples sided with the British, and when the British decided to settle for peace (mainly because of their need to deal with Napoleon rather than losing militarily to the Americans), they stopped supporting their allies. Without British protection, there was no stopping the Americans from moving in.

In 1819, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun (the slave owner whose theories of the nullification of federal laws and secession created the seeds for the Civil War) asked Michigan’s territorial governor, Lewis Cass, to negotiate with the indigenous people to cede Saginaw Valley. Cass designated what is today the city of Saginaw as the official meeting place, mainly because regional Native Americans often used it for this purpose. Fur trader Louis Campau, who’d established the first permanent trading post here, was asked by Cass to spread the word of the meeting, build a council house, and prepare quarters for Cass and his entourage. Three meetings took place here between September 10 and 24, 1819, and out of these came the Treaty of Saginaw that Congress ratified on March 2, 1820. In exchange for giving up six million acres of land, the Native Americans who signed on were given sixteen reservations, $3,000 in silver coins, and $1,000 a year in perpetuity.

It’s at this point things went bad for the native people living here. Americans were land hungry and wanted to move in permanently. During the War of 1812 the majority of Michigan’s and Ohio’s native peoples sided with the British, and when the British decided to settle for peace (mainly because of their need to deal with Napoleon rather than losing militarily to the Americans), they stopped supporting their allies. Without British protection, there was no stopping the Americans from moving in.

In 1819, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun (the slave owner whose theories of the nullification of federal laws and secession created the seeds for the Civil War) asked Michigan’s territorial governor, Lewis Cass, to negotiate with the indigenous people to cede Saginaw Valley. Cass designated what is today the city of Saginaw as the official meeting place, mainly because regional Native Americans often used it for this purpose. Fur trader Louis Campau, who’d established the first permanent trading post here, was asked by Cass to spread the word of the meeting, build a council house, and prepare quarters for Cass and his entourage. Three meetings took place here between September 10 and 24, 1819, and out of these came the Treaty of Saginaw that Congress ratified on March 2, 1820. In exchange for giving up six million acres of land, the Native Americans who signed on were given sixteen reservations, $3,000 in silver coins, and $1,000 a year in perpetuity.

In 1970, the construction of a new federal building eliminated the need for Castle all together, and it stopped being a post office in 1976. Once again proposals to demolish it were made, but Saginaw County came to the rescue by buying the building. In 1979, the country repurposed it as the its historical museum.

The main hall into which you begin your tour of the museum is lined exhibits. Here four terra cotta lionheads caught my eye. These had once decorated the Saginaw Daily News Building, which was built in 1916. It stood until 1960 when it was replaced by a new structure. Rosemary DeGesero, who’d opposed the demolition, saved the lionheads and affixed them to her front porch where they stayed perched for the next fifty years. The lionheads were moved to the museum when the city of Saginaw bought DeGersero’s house.

In the exhibit that covers the history of the Castle during its time as a post office, there is a staircase with a sign saying that it leads to the “observation gallery.” The stairs take you to a long hallway along which are small slits. It’s through these that post office inspectors once watched the workers below to make sure they didn’t steal, with several work areas being observable from here. The hall was painted black to make it difficult if not impossible for those below to see up into it, a means of maintaining its secrecy: only a select few knew it existed.

The main hall into which you begin your tour of the museum is lined exhibits. Here four terra cotta lionheads caught my eye. These had once decorated the Saginaw Daily News Building, which was built in 1916. It stood until 1960 when it was replaced by a new structure. Rosemary DeGesero, who’d opposed the demolition, saved the lionheads and affixed them to her front porch where they stayed perched for the next fifty years. The lionheads were moved to the museum when the city of Saginaw bought DeGersero’s house.

In the exhibit that covers the history of the Castle during its time as a post office, there is a staircase with a sign saying that it leads to the “observation gallery.” The stairs take you to a long hallway along which are small slits. It’s through these that post office inspectors once watched the workers below to make sure they didn’t steal, with several work areas being observable from here. The hall was painted black to make it difficult if not impossible for those below to see up into it, a means of maintaining its secrecy: only a select few knew it existed.

Surveyors moved in. The short-lived Fort Saginaw was built to ensure Native Americans not keen to be displaced from their homeland wouldn’t make trouble. Saginaw County was carved out of this region. Although officially established on January 28, 1835, it wasn’t until 1881 that its present borders were settled.

Michigan achieved statehood on January 26, 1837. In that same year and into the next, the indigenous people living on the reservations established by the Treaty of Saginaw were compelled by the federal government to move west of the Mississippi, leaving abandoned their lands open for American settlers. They rushed in as did land speculators. The boom caused by the latter came crashing down with the Panic of 1837, an event that today would be considered an economic depression. Work on a canal connecting Gratiot County’s Bad and Maple Rivers began in 1897, but by 1839 it was abandoned due to a lack of funds.

The year before the panic, Norman Little along with New York financiers William Jenson and Samuel Oakley bought the remaining lots on the west side of the Saginaw River. Little, who was born and raised in New York State, had a vision of creating a “Saginaw City,” which would serve as the region’s center. Construction started on a few key buildings including a bank and courthouse, but the cascading effects of the Panic of 1837 caused Little’s venture to collapse the next year.

Michigan achieved statehood on January 26, 1837. In that same year and into the next, the indigenous people living on the reservations established by the Treaty of Saginaw were compelled by the federal government to move west of the Mississippi, leaving abandoned their lands open for American settlers. They rushed in as did land speculators. The boom caused by the latter came crashing down with the Panic of 1837, an event that today would be considered an economic depression. Work on a canal connecting Gratiot County’s Bad and Maple Rivers began in 1897, but by 1839 it was abandoned due to a lack of funds.

The year before the panic, Norman Little along with New York financiers William Jenson and Samuel Oakley bought the remaining lots on the west side of the Saginaw River. Little, who was born and raised in New York State, had a vision of creating a “Saginaw City,” which would serve as the region’s center. Construction started on a few key buildings including a bank and courthouse, but the cascading effects of the Panic of 1837 caused Little’s venture to collapse the next year.

Unable to regain the land lost on the west side of the Saginaw River, in 1849 he and New York partners Jesse and James M. Hoyt bought 2,400 acres of land on river’s east side, and here founded East Saginaw. A year earlier, Little had asked the Michigan legislature for a charter to build a plank road connecting the planned city to Flint, a stretch of about thirty-two miles. At first the legislature was hesitant to grant it, but it then decided that if this fool Little wanted to build a road through swampy land, it would let him. Not only was the road a success, it helped make East Saginaw and Saginaw City into affluent communities.

One driver of this prosperity was the lumber industry. In 1850 about ninety percent of Michigan was covered with thick, virgin forests dominated by the Eastern White Pine. By this time forests in the eastern part of the nation had been pretty much cut down, so lumber harvesting started in the Saginaw Valley, booming after the Civil War. East Saginaw and Saginaw City became known as the Lumber Capital of the World. It was predicted that Saginaw Valley’s trees could supply the needs of the United States for a century, a forecast that was far off the mark.

Lumber output peeked in 1882. By the 1890s the trees were nearly all gone, causing many sawmills to fall silent. An estimated 23 billion board feet of lumber is believed to have been extracted from the region in the nineteenth century. East Saginaw and Saginaw City merged and became present-day Saginaw in March 1890, but the collapse of the lumber industry caused it to lose ten percent of its population over the next decade.

One driver of this prosperity was the lumber industry. In 1850 about ninety percent of Michigan was covered with thick, virgin forests dominated by the Eastern White Pine. By this time forests in the eastern part of the nation had been pretty much cut down, so lumber harvesting started in the Saginaw Valley, booming after the Civil War. East Saginaw and Saginaw City became known as the Lumber Capital of the World. It was predicted that Saginaw Valley’s trees could supply the needs of the United States for a century, a forecast that was far off the mark.

Lumber output peeked in 1882. By the 1890s the trees were nearly all gone, causing many sawmills to fall silent. An estimated 23 billion board feet of lumber is believed to have been extracted from the region in the nineteenth century. East Saginaw and Saginaw City merged and became present-day Saginaw in March 1890, but the collapse of the lumber industry caused it to lose ten percent of its population over the next decade.

It was known since the 1850s that a large amount of coal lay beneath Saginaw Valley, but until the 1890s there were no successful efforts to mine it. The loss of the lumber industry prompted the creation of many coal mines in the 1890s. More of these were registered in Saginaw County than any other in Michigan. The mining boom didn’t last long in part because of the valley’s geology. Veins were about 100 to 200 feet below the surface and tended, says a museum information sign, to “end abruptly.” Water filled them, requiring constant pumping. The last coal mine in Saginaw Valley closed in 1952.

Automobile manufacturing became Saginaw’s next big industry. The National Engineering Company started making crankshafts in 1912 with one of its customers being General Motors. Sold in 1916 to Lansing investors, it was sold again 1921 to GM itself. Grey Iron Foundry started making GM parts in 1919. Saginaw Malleable Iron Foundry started in 1917 and was purchased by GM in 1919. Saginaw also had native car and bike companies including the short-lived Rainer Motor Company, which lasted from 1905 to 1910.

While lumber, coal and the auto industry would become some of the biggest economic drivers in Saginaw County, those who worked in them still needed to eat. One source of food came from hucksters who carried fresh produce on horse-drawn wagons with which they traveled regular routes throughout Saginaw and beyond. “Huckster” is the Dutch word for peddler. Hucksters bought their fruits and vegetables at City Market each day, then hoped to sell everything by the day’s end with no spoilage.

Automobile manufacturing became Saginaw’s next big industry. The National Engineering Company started making crankshafts in 1912 with one of its customers being General Motors. Sold in 1916 to Lansing investors, it was sold again 1921 to GM itself. Grey Iron Foundry started making GM parts in 1919. Saginaw Malleable Iron Foundry started in 1917 and was purchased by GM in 1919. Saginaw also had native car and bike companies including the short-lived Rainer Motor Company, which lasted from 1905 to 1910.

While lumber, coal and the auto industry would become some of the biggest economic drivers in Saginaw County, those who worked in them still needed to eat. One source of food came from hucksters who carried fresh produce on horse-drawn wagons with which they traveled regular routes throughout Saginaw and beyond. “Huckster” is the Dutch word for peddler. Hucksters bought their fruits and vegetables at City Market each day, then hoped to sell everything by the day’s end with no spoilage.

7 One of Saginaw’s hucksters was James Licavoli, who emigrated from Sicily to Saginaw in 1904 at the age of fourteen. He started his huckster business with a pushcart, then graduated to a horse-drawn wagon. He worked long hours six days a week year round to support his wife and eleven children. By 1929 he needed to replace his wagon, but with it being the Great Depression, he lacked the funds to buy one. His eldest son, Phillip, saved money up from his paper route and surprised his father with the gift of a brand new custom-built wagon. (That must’ve been one lucrative paper route!)

In the summer, Licavoli soaked sacks in cold water to keep his produce fresh, replacing dried bags with wet ones as the day passed. In the winter he kept the produce from freezing with a stove. Most hucksters burned kerosene, but he always used wood or coal because he felt that kerosene affected the taste of the produce he sold. After his retirement in 1955, his nephew, Sam Licavoli, bought the wagon and continued with the business.

Using coal for heating like Licavoli did has a serious downside: it leaves a film of black grime behind. Most American houses and apartments were heated by coal in the first half of the twentieth century, requiring regular cleaning to remove the soot. One evening two Saginaw women, Naomi Mae Stenglein and Elizabeth MacDonald, were visiting with one another. Their conversation turned to complaining about their forthcoming spring cleaning. At this time the only way to effectively remove coal soot off of floors, walls and furniture was to wash them with soapy water produced a film. This was rinsed off with clean hot water that left behind streaks which had to be wiped off with a dry cloth. Someone, the two women pondered, ought to make a product that could clean in a single wash.

In the summer, Licavoli soaked sacks in cold water to keep his produce fresh, replacing dried bags with wet ones as the day passed. In the winter he kept the produce from freezing with a stove. Most hucksters burned kerosene, but he always used wood or coal because he felt that kerosene affected the taste of the produce he sold. After his retirement in 1955, his nephew, Sam Licavoli, bought the wagon and continued with the business.

Using coal for heating like Licavoli did has a serious downside: it leaves a film of black grime behind. Most American houses and apartments were heated by coal in the first half of the twentieth century, requiring regular cleaning to remove the soot. One evening two Saginaw women, Naomi Mae Stenglein and Elizabeth MacDonald, were visiting with one another. Their conversation turned to complaining about their forthcoming spring cleaning. At this time the only way to effectively remove coal soot off of floors, walls and furniture was to wash them with soapy water produced a film. This was rinsed off with clean hot water that left behind streaks which had to be wiped off with a dry cloth. Someone, the two women pondered, ought to make a product that could clean in a single wash.

When their husbands—Harold Stenglein and Glenn MacDonald—overheard this, they thought their wives’ idea might make some money. Elizabeth had heard that mixing glue in wash water could avoid producing soap scum and streaking, so for months experiments with different glues were made, mostly by the women. The final formula consisted of powdered hide glue, trisodium phosphate and sodium carbonate. It worked as hoped. Harold and Glenn convinced local businesses to sell it. Christened “Spic and Span” by Naomi, Protect & Gamble bought the rights to it in 1945 for nearly $2 million dollars—about $34 million today.

Another item that sold well in Saginaw was water from St. Louis, a small town about thirty-three miles away at which a mineral spring produced water rich with bicarbonate of lime, bicarbonate of magnesia, and sulfate of lime. Saginaw company St. Louis Magnetic Spring Water sold it in bottles. While claims that the water could cure everything from cancer to rheumatism were bogus, it was a healthy alternative to drinking water that came from the polluted Saginaw River.

In addition to industries and the goods they created, Saginaw also produced talent, such a jazz great Sonny Stitt. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, on February 2, 1924, as Edward Boatner, Jr., a museum information sign says, “his father was a famous composer of Negro Spirituals and his mother was a piano teacher.” He was put up for adoption when his parents divorced. The Stitt family in Saginaw adopted him. As he grew up, he began playing the saxophone, with jazz being his preferred type of music. Extremely talented, he went professional, taking on the stage name Sonny Stitt. In 1945 he replaced saxophonist Charlie Parker in Dizzy Gillespie’s band. Over his lifetime he was both a sideman and band leader. He played with such giants as Miles Davis and Bud Powell. By the time of his death in 1982, he had recorded on over 300 albums.🕜

Another item that sold well in Saginaw was water from St. Louis, a small town about thirty-three miles away at which a mineral spring produced water rich with bicarbonate of lime, bicarbonate of magnesia, and sulfate of lime. Saginaw company St. Louis Magnetic Spring Water sold it in bottles. While claims that the water could cure everything from cancer to rheumatism were bogus, it was a healthy alternative to drinking water that came from the polluted Saginaw River.

In addition to industries and the goods they created, Saginaw also produced talent, such a jazz great Sonny Stitt. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, on February 2, 1924, as Edward Boatner, Jr., a museum information sign says, “his father was a famous composer of Negro Spirituals and his mother was a piano teacher.” He was put up for adoption when his parents divorced. The Stitt family in Saginaw adopted him. As he grew up, he began playing the saxophone, with jazz being his preferred type of music. Extremely talented, he went professional, taking on the stage name Sonny Stitt. In 1945 he replaced saxophonist Charlie Parker in Dizzy Gillespie’s band. Over his lifetime he was both a sideman and band leader. He played with such giants as Miles Davis and Bud Powell. By the time of his death in 1982, he had recorded on over 300 albums.🕜

Sturgeon are one of the fish in the Saginaw River.