Century Village Museum

I have a particular fondness for living museums that recreate a historical moment in time, such as the one in Williamsburg, Virginia. Century Village Museum, which is operated by the Geauga County Historical Society (GCHS), is this type. Located in Burton, it represents a nineteenth century village using historical buildings mostly brought to the site from elsewhere. The day I visited I lucked out. No one had come for the eleven o’clock tour except for me, so I got a one-on-one one tour from Karen J. Hale, a registered nurse, professor, and history enthusiast.

The museum opened on May 30, 1942, with the Eleazer Hickox House as its only building. The idea for the GCHS was conceived at an 1873 family reunion at which descendants of John and Ester Ford gathered. The idea of forming a Geauga County historical society was proposed by Colonel Henry Ford who discussed the idea with his guests Lester Taylor, Homer Godwin, and General James Garfield, who in 1880 would be elected president of United States only to be cut down by an assassin’s bullet the next year. The GCHS’s constitution was introduced on September 16, 1873, with Garfield giving a speech that day. Because its members found it difficult to get to meetings, it languished for a time until resurrected by B.J. Shanower on July 4, 1935. The six and one-half acres of land on which the present site stands was donated in 1941 by Frances P. Bolton, the first women elected by Ohio to go to the U.S. House of Representatives.

The Hickox House in which Stella lived was built by Eleazer Hickox in 1838. It’s one of two buildings original to the Century Village site, other being the White Barn, so called because of its color. The original part of the Hickox House was made of brick and the later addition of wood. Part of its first floor is set up to show how a wealthy family lived in the nineteenth century while the rest exhibits Civil War artifacts from local families that includes a prosthetic arm with a hook.

The first exhibit you see upon entering the Hickox House is a display of mechanical banks behind glass. This type of savings plan was first introduced around 1800. The earliest ones were probably made of wood or lead. About 1860 the manufacturer John Hall began producing the tin Excelsior, the first mass produced mechanical bank to sell well. Other materials used for these banks included pottery and glass. After the Civil War, cast iron became the dominant material. It is possible some of the ones on display in the Hickox House are worth a lot because some of these antiques are highly sought by collectors. There is a thriving market for fakes.

Hanging on the house’s walls are several paintings by Ohio artist Archibald Willard, whose most famous work is The Spirit of ’76. In one of the rooms is a painting of his favorite nephew (who died young) for which Willard only did the face. Although the painting is, to be blunt, pretty awful, it does have one interesting feature. The face’s eyes watch you no matter what angle you look at it. This is a technique Willard had recently learned, though it’s not much of trick once you know its secret. Any painting with realistic three-dimensional eyes that look directly at the viewer will appear to follow you as you move from one side of the painting to the other.

The Hickox House in which Stella lived was built by Eleazer Hickox in 1838. It’s one of two buildings original to the Century Village site, other being the White Barn, so called because of its color. The original part of the Hickox House was made of brick and the later addition of wood. Part of its first floor is set up to show how a wealthy family lived in the nineteenth century while the rest exhibits Civil War artifacts from local families that includes a prosthetic arm with a hook.

The first exhibit you see upon entering the Hickox House is a display of mechanical banks behind glass. This type of savings plan was first introduced around 1800. The earliest ones were probably made of wood or lead. About 1860 the manufacturer John Hall began producing the tin Excelsior, the first mass produced mechanical bank to sell well. Other materials used for these banks included pottery and glass. After the Civil War, cast iron became the dominant material. It is possible some of the ones on display in the Hickox House are worth a lot because some of these antiques are highly sought by collectors. There is a thriving market for fakes.

Hanging on the house’s walls are several paintings by Ohio artist Archibald Willard, whose most famous work is The Spirit of ’76. In one of the rooms is a painting of his favorite nephew (who died young) for which Willard only did the face. Although the painting is, to be blunt, pretty awful, it does have one interesting feature. The face’s eyes watch you no matter what angle you look at it. This is a technique Willard had recently learned, though it’s not much of trick once you know its secret. Any painting with realistic three-dimensional eyes that look directly at the viewer will appear to follow you as you move from one side of the painting to the other.

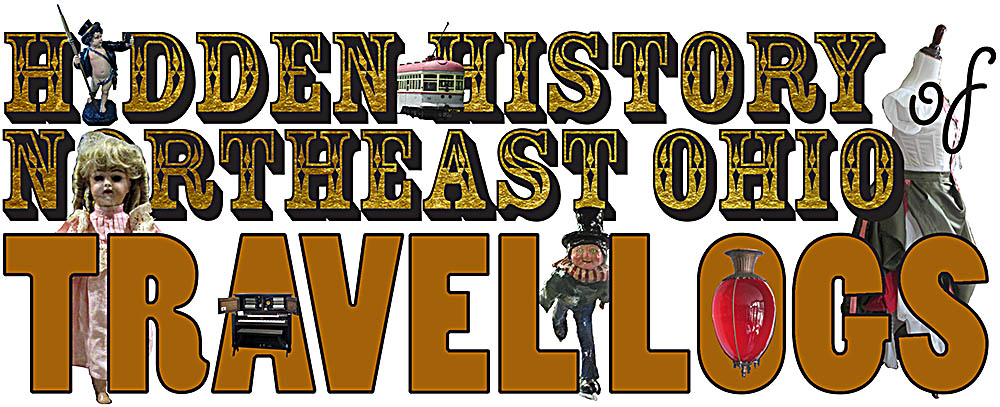

The White Barn, built for Eleazer Hickox in 1840, over the years has had a variety of purposes, including hosting an art show, serving as a supper club during the Apple Butter Festival, and as the home of the giftshop Sheauga’s Treasures. Today it serves as a place for artisans to work, and it contains exhibits that include an extensive collection of Native American artifacts and a wagon that carried the Hazen family to Geauga County in 1827. Everything from its wheels to its base is original. The rest, including the sides and canvas top, were added so visitors can see it as it looked during its journey. My guide told me it is a Conestoga wagon, but it isn’t. It is far too small and shaped wrong to be one.

Conestoga wagons were the late eighteenth and early nineteen centuries equivalent to the modern semitruck and trailer, not the sort of thing a family would use. They originated in Pennsylvania along the Conestoga River near Lancaster. Originally manufactured by German immigrants, they had a flexible undercarriage designed to negotiate America’s rotten roads where they existed, and could carry four to six tons of goods. General Edward Braddock used them during the French and Indian War as did General George Washington during the Revolution. After the latter conflict, the wagons hauled goods over the Appalachians into the Ohio Valley. Their curved shape made it less likely that goods could fall out on steep inclines.

It took about two months to make one of these behemoths, which were around sixteen feet long and four feet wide. Selling for about $200, they were pulled by a team of four horses harnessed with bells that served as a status symbol for the drivers, who usually walked alongside the wagons and controlled their horses with a rein on wagon’s left side. By the outbreak of the Civil War, Conestoga wagons were no longer made. They certainly weren’t the wagons that took pioneers into the West. Those were prairie schooners, a lighter vehicle usually pulled by oxen or mules. Drivers sat atop the wagon with the reins in the center.

Another building brought to the Century Village campus was the Cottage Grocery Store, which now serves as an apothecary in its front half and a doctor’s office in its back half. The apothecary portion is jampacked with medical instruments, medicine bottles, and information about nineteenth century medicine. In that era some doctors still bled patients, as attested by the bleeding bowl on display. They also used leeches to pull out excess blood after an amputation, which, once they had their fill, would fall off. One of the grossest things I learned here was the existence of the puking pill, which caused that reaction and was then reused by someone else after its return.

Apothecaries would impress customers with ellipsoids made of colored glass called show globes. These originated in the seventeenth century and were used in the United States, Canada and Great Britain. No one knows their exact origin. Probably they reflected the fact that apothecaries could compound all sorts of vibrant colors by mixing chemicals, a source of pride for its practitioners. Supposedly when an apothecary put out a red globe, this warned potential customers there was a plague or quarantine. Green meant all was well.

Trying to pin down the difference between an apothecary and pharmacist is not as simple as it might sound. Some sources say they are one in the same. More confusing, the word “apothecary” refers to both the person who created drugs and the business from which they were sold. Best I can tell, one was an apothecary if he or she made the medicine from scratch by mixing, or compounding, the ingredients, then producing the final product in whatever form it was dispensed. A pharmacist, in contrast, dispensed medicine made elsewhere.

Conestoga wagons were the late eighteenth and early nineteen centuries equivalent to the modern semitruck and trailer, not the sort of thing a family would use. They originated in Pennsylvania along the Conestoga River near Lancaster. Originally manufactured by German immigrants, they had a flexible undercarriage designed to negotiate America’s rotten roads where they existed, and could carry four to six tons of goods. General Edward Braddock used them during the French and Indian War as did General George Washington during the Revolution. After the latter conflict, the wagons hauled goods over the Appalachians into the Ohio Valley. Their curved shape made it less likely that goods could fall out on steep inclines.

It took about two months to make one of these behemoths, which were around sixteen feet long and four feet wide. Selling for about $200, they were pulled by a team of four horses harnessed with bells that served as a status symbol for the drivers, who usually walked alongside the wagons and controlled their horses with a rein on wagon’s left side. By the outbreak of the Civil War, Conestoga wagons were no longer made. They certainly weren’t the wagons that took pioneers into the West. Those were prairie schooners, a lighter vehicle usually pulled by oxen or mules. Drivers sat atop the wagon with the reins in the center.

Another building brought to the Century Village campus was the Cottage Grocery Store, which now serves as an apothecary in its front half and a doctor’s office in its back half. The apothecary portion is jampacked with medical instruments, medicine bottles, and information about nineteenth century medicine. In that era some doctors still bled patients, as attested by the bleeding bowl on display. They also used leeches to pull out excess blood after an amputation, which, once they had their fill, would fall off. One of the grossest things I learned here was the existence of the puking pill, which caused that reaction and was then reused by someone else after its return.

Apothecaries would impress customers with ellipsoids made of colored glass called show globes. These originated in the seventeenth century and were used in the United States, Canada and Great Britain. No one knows their exact origin. Probably they reflected the fact that apothecaries could compound all sorts of vibrant colors by mixing chemicals, a source of pride for its practitioners. Supposedly when an apothecary put out a red globe, this warned potential customers there was a plague or quarantine. Green meant all was well.

Trying to pin down the difference between an apothecary and pharmacist is not as simple as it might sound. Some sources say they are one in the same. More confusing, the word “apothecary” refers to both the person who created drugs and the business from which they were sold. Best I can tell, one was an apothecary if he or she made the medicine from scratch by mixing, or compounding, the ingredients, then producing the final product in whatever form it was dispensed. A pharmacist, in contrast, dispensed medicine made elsewhere.

The doctor’s office in the back of the Cottage Grocery Store is a replica of one that belonged to Walter Corey in Charon as it looked around 1945. Born in 1890, Corey worked as a doctor for forty-six years and during that time was the first person to fill position of health commissioner for Geauga County. Despite the fact Chardon is in the snowbelt, he made house calls in winter. In the days before snow tires, he equipped his car with oversized tires to get through and, if that failed, he traveled using a tractor with a snowplow attached to its front.During his many years of practice, he delivered about 4,000 of Geauga County’s babies and removed the tonsils of many of its children. This he only did in the summer so they wouldn’t miss school. He was quite a character and had a good sense of humor. In the 1940s he started the Corey Hospital in Chardon. He died in his own hospital at the age of 81 on January 30, 1972.

Next door to Corey’s office is the Crossroads Store, one of two general stores on the premises. This one contains a giftshop and is where you purchase a ticket and begin your tour. The other one, the Old Bainbridge Store, was built around 1846 by William Smith. Frank Jaros bought it in 1924, running it until 1941 at which time his family rented the property to other proprietors. The store finally closed its doors in 1971 when the new Route 422 prompted the family’s executor, Lawrence Jaros, to sell the land on which it stood. The building itself was then donated to GCHS, which moved it to its present location.

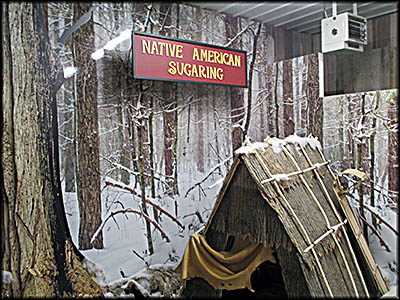

A number of interesting items can be found within including a Zeno chewing gum machine that dispensed sticks of gum. The concept of chewing gum goes back at least 9,000 years. The oldest piece of honey-flavored gum is 9,000 years and was unearthed by archeologists in Sweden. Made from birchbark tar, it was chewed by Neolithic people of German stock. The ancient Greeks chewed the resin of the mastic tree. Americans—both Native and those whose origins lie elsewhere—used to chew spruce tree resin despite its horrid flavor. Indeed, one of the first successful American chewing gums was made of this. Introduced by Jacob Bacon Curtis of Maine in 1841, it sold as State of Maine Pure Spruce Gum.

In the 1850s, Thomas Adams of New York City worked for Antonio López Santa Anna, the former president of Mexico (on multiple occasions) and the man who ordered the slaughter of all the Alamo’s defenders. At this time he was in exile and living on Long Island of all places. He asked Adams to see if he could make chicle, a sap produced by the sapodilla tree found mainly in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula as well as in Central America, into a rubber substitute. Santa Anna hoped it would generate the revenue he needed to return to Mexico and seize power once more, but the venture went no where because chicle doesn’t bounce.

One day Adams saw a young girl walking out of a drugstore chewing paraffin gum and it occurred to him the otherwise useless chicle might work better than a wax for this purpose. (It wasn’t an original idea. The ancient Mayans chewed chicle.) Adams’ gum flavors included tutti-frutti and licorice. He first marketed his gum as Adams New York No. 1. The licorice flavored gum he made was mass marketed as Black Jack, which you can still purchase today.

But back to Zeno gum. William N. Brewer, who worked at a Chicago subsidiary of the Cleveland-based Rubber Paint Company, had the idea of making chewing gum made of rubber, which was one of the ingredients in the company’s paint. In 1890 the Rubber Paint Company created the Zeno Manufacturing Company to make chewing gum in a variety flavors including vanilla cream, peppermint, orange, and licorice. Stores that ordered 1,200 sticks got with it a free vending machine.

At the same time that production of Zeno gum began in Chicago, a salesman originally from Philadelphia named William Wrigley, Jr. was selling soap and baking powder. As a gimmick to increase sales, Wrigley gave two sticks of Zeno gum with his baking powder. Seeing that the gum was the more popular of the two, he started selling it exclusively with Zeno providing his supply. In 1910 Wrigley’s distribution company merged with Zeno to become the William Wrigley, Jr. Company, at which point the Zeno brand ended.

Wrigley introduced the flavors juicy fruit and spearmint and advertised mercilessly. He gave millions of sticks away free. His gum appeared on billboards, placards, and electric signs across America. It made him a fortune, and with this he began buying major and minor league baseball teams. He also purchased Santa Clara Island off of Los Angeles’ coast on which he built a vacation resort complete with a wildlife sanctuary that those from the middle class could afford.

More about Century Village can be found in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the Geauga County chapter.🕜

Next door to Corey’s office is the Crossroads Store, one of two general stores on the premises. This one contains a giftshop and is where you purchase a ticket and begin your tour. The other one, the Old Bainbridge Store, was built around 1846 by William Smith. Frank Jaros bought it in 1924, running it until 1941 at which time his family rented the property to other proprietors. The store finally closed its doors in 1971 when the new Route 422 prompted the family’s executor, Lawrence Jaros, to sell the land on which it stood. The building itself was then donated to GCHS, which moved it to its present location.

A number of interesting items can be found within including a Zeno chewing gum machine that dispensed sticks of gum. The concept of chewing gum goes back at least 9,000 years. The oldest piece of honey-flavored gum is 9,000 years and was unearthed by archeologists in Sweden. Made from birchbark tar, it was chewed by Neolithic people of German stock. The ancient Greeks chewed the resin of the mastic tree. Americans—both Native and those whose origins lie elsewhere—used to chew spruce tree resin despite its horrid flavor. Indeed, one of the first successful American chewing gums was made of this. Introduced by Jacob Bacon Curtis of Maine in 1841, it sold as State of Maine Pure Spruce Gum.

In the 1850s, Thomas Adams of New York City worked for Antonio López Santa Anna, the former president of Mexico (on multiple occasions) and the man who ordered the slaughter of all the Alamo’s defenders. At this time he was in exile and living on Long Island of all places. He asked Adams to see if he could make chicle, a sap produced by the sapodilla tree found mainly in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula as well as in Central America, into a rubber substitute. Santa Anna hoped it would generate the revenue he needed to return to Mexico and seize power once more, but the venture went no where because chicle doesn’t bounce.

One day Adams saw a young girl walking out of a drugstore chewing paraffin gum and it occurred to him the otherwise useless chicle might work better than a wax for this purpose. (It wasn’t an original idea. The ancient Mayans chewed chicle.) Adams’ gum flavors included tutti-frutti and licorice. He first marketed his gum as Adams New York No. 1. The licorice flavored gum he made was mass marketed as Black Jack, which you can still purchase today.

But back to Zeno gum. William N. Brewer, who worked at a Chicago subsidiary of the Cleveland-based Rubber Paint Company, had the idea of making chewing gum made of rubber, which was one of the ingredients in the company’s paint. In 1890 the Rubber Paint Company created the Zeno Manufacturing Company to make chewing gum in a variety flavors including vanilla cream, peppermint, orange, and licorice. Stores that ordered 1,200 sticks got with it a free vending machine.

At the same time that production of Zeno gum began in Chicago, a salesman originally from Philadelphia named William Wrigley, Jr. was selling soap and baking powder. As a gimmick to increase sales, Wrigley gave two sticks of Zeno gum with his baking powder. Seeing that the gum was the more popular of the two, he started selling it exclusively with Zeno providing his supply. In 1910 Wrigley’s distribution company merged with Zeno to become the William Wrigley, Jr. Company, at which point the Zeno brand ended.

Wrigley introduced the flavors juicy fruit and spearmint and advertised mercilessly. He gave millions of sticks away free. His gum appeared on billboards, placards, and electric signs across America. It made him a fortune, and with this he began buying major and minor league baseball teams. He also purchased Santa Clara Island off of Los Angeles’ coast on which he built a vacation resort complete with a wildlife sanctuary that those from the middle class could afford.

More about Century Village can be found in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the Geauga County chapter.🕜

Apothecary

Cook House

Get your tickets here.

Inside the School House

White Barn

Hazen Family Wagon

Inside the Maple Syrup Museum

Zeno Gum Machine

Railroad Depot

Sawmill

Show Globe