Cooke-Dorn House

Cooke-Dorn House Entrance

Garage and Greenhouse

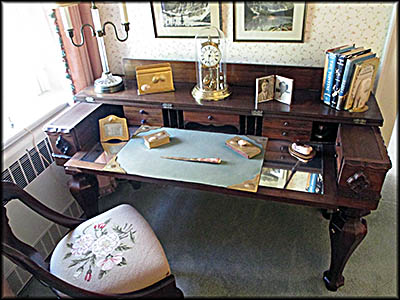

Eleutheros Cooke

Living Room

This chandelier was purchased

by Jay Cooke for his parents.

by Jay Cooke for his parents.

Dining Room Table

Powder Room

Kitchen

Vintage Cabinet Color Television ca. 1964.

On the bed in the master bedroom is a dress once worn by Estelle Dorn.

Guest Sitting Room

This scene In the dining room is hand-painted wallpaper.

The Cooke-Dorn House wasn’t the place I expected. I thought it was the house in which Jay Cooke lived as a child. Cooke, who was born in Sandusky, Ohio, financed the Civil War and founded America’s first investment bank. Not only did he never live in the Cooke-Dorn house, it isn’t even in the same location as it was during his lifetime (more on that later).

The house was built by Cooke’s father, Eleutheros (which means “free” in Greek). Eleutheros was born in Granville, New York, on Christmas Day 1787. He was a lawyer by trade. His family traced its roots all the way back to King Charlemagne of France, who died in 878. Eleutheros’ more immediate forefathers landed in America at Plymouth. He married Martha Simpson Carswell in December 1812, and in 1816 moved her and his daughter, Sarah, to Madison, Indiana, which is on the Ohio River. Getting to Madison was a relatively easy venture because boats continuously traveled down the Ohio. But going up river could be done by a steamboat, few of which plied the Ohio at the time. In Summer 1817, Eleutheros was called back to New York for business, so traveled overland to reach the southern shore of Lake Erie from which he’d take a ship to his destination.

During his trek through Ohio, which was still largely wilderness and had little infrastructure, Eleutheros met an acquaintance, Charles Drake, at the small settlement of Bloomingville. Drake took his friend to Venice whose owner, Frederic Falley, paid Eleutheros to draw up contacts for lots. While here, Eleutheros also drew up contracts for mills, roads, and other such places, earning more than he’d ever had in Madison. Seeing an opportunity, he bought several hundred acres of land in Bloomingville.

He didn’t return to Madison 1818. He decamped with his family, taking them to Bloomingville. Reaching it on sleighs in November, he learned that an outbreak of disease had made Venice a ghost town. He frequently traveled to Sandusky, a day long trip at this time, and in 1821 he moved his growing family there. He was the town’s first lawyer, and he built its first stone house. During its construction he and his family lived in a cottage owned by Doctor Anderson, and it’s here that his son Jay was born.

Shortly thereafter the Cooke family moved into their new house. The house was in what was then known as Hell’s Half Acre (historians don’t know where that appellation came from), and when Jay was six, Eleutheros relocated to a new stone house. The original no longer stands, although one of its walls is part of what is now the Barra Restaurant.

During his trek through Ohio, which was still largely wilderness and had little infrastructure, Eleutheros met an acquaintance, Charles Drake, at the small settlement of Bloomingville. Drake took his friend to Venice whose owner, Frederic Falley, paid Eleutheros to draw up contacts for lots. While here, Eleutheros also drew up contracts for mills, roads, and other such places, earning more than he’d ever had in Madison. Seeing an opportunity, he bought several hundred acres of land in Bloomingville.

He didn’t return to Madison 1818. He decamped with his family, taking them to Bloomingville. Reaching it on sleighs in November, he learned that an outbreak of disease had made Venice a ghost town. He frequently traveled to Sandusky, a day long trip at this time, and in 1821 he moved his growing family there. He was the town’s first lawyer, and he built its first stone house. During its construction he and his family lived in a cottage owned by Doctor Anderson, and it’s here that his son Jay was born.

Shortly thereafter the Cooke family moved into their new house. The house was in what was then known as Hell’s Half Acre (historians don’t know where that appellation came from), and when Jay was six, Eleutheros relocated to a new stone house. The original no longer stands, although one of its walls is part of what is now the Barra Restaurant.

In addition to his work as a lawyer, Eleutheros got into politics. He was elected to Sandusky’s first city council, served as a state legislature and one term in Congress as a representative. He convinced his friend David Campbell from New York to come to Sandusky and start a newspaper. Campbell began publishing it in 1821, and it’s still in print under the name Sandusky Register. Eleutheros helped found a high school that was running by 1845, he was involved with the construction of two primary schools, and he facilitated the building of Grace Episcopal Church.

But wait, there’s more. He was one of the founders of the Firelands Historical Society. Had had two more stone houses built that he rented out. He was a big promoter of the Mad River & Lake Erie Railroad—the first railroad chartered west of the Allegheny Mountains. Construction began on September 17, 1835 in what is now Sandusky’s Battery Park.

But before we put Eleutheros on a pedestal, let’s remember that he was only human and, in some ways, not an especially good one. The land sales that created his wealth was stolen from the Wyandots after the United States reneged on the treaty guaranteeing it was theirs. Eleutheros was of the first generation to benefit from this conquest. To be fair, few Americans of that era considered this wrong, though there were dissenting voices including Davy Crockett, Christian missionary Jeremiah Evarts, and even the Supreme Court. If this bothered Eleutheros, none of the biographical information I found about him mentioned it.

But wait, there’s more. He was one of the founders of the Firelands Historical Society. Had had two more stone houses built that he rented out. He was a big promoter of the Mad River & Lake Erie Railroad—the first railroad chartered west of the Allegheny Mountains. Construction began on September 17, 1835 in what is now Sandusky’s Battery Park.

But before we put Eleutheros on a pedestal, let’s remember that he was only human and, in some ways, not an especially good one. The land sales that created his wealth was stolen from the Wyandots after the United States reneged on the treaty guaranteeing it was theirs. Eleutheros was of the first generation to benefit from this conquest. To be fair, few Americans of that era considered this wrong, though there were dissenting voices including Davy Crockett, Christian missionary Jeremiah Evarts, and even the Supreme Court. If this bothered Eleutheros, none of the biographical information I found about him mentioned it.

Work on his final stone house—the one I toured—began in 1843 and finished in 1844. The man who built this and all of Eleutheros’ other houses was William Kelly. He also constructed Marblehead Lighthouse, the oldest operating one on the Great Lakes. This house would serve as Eleutheros’ retirement home. His son, Jay, visited it for the first time in 1845 during his honeymoon. Eleutheros died in 1864 at the age of seventy-seven. His wife, Martha, passed on in 1878 at the age of eighty-six.

After the latter’s death, the house was sold to Rush R. Sloan on April 11, 1879. He decided to move it a mile north on Columbus Avenue, the place where it still currently stands. He hired Jacob Beihl to oversee this project. Beihl diagramed the house, then oversaw its dismantling and reconstruction. He did such a good job only one stone was missing when the project was finished. Sloan had modifications done to the house that included a deeper basement, replacing a flat roof with a peaked one, installing central heating, and moving the servants’ quarters. On the lot from which the house was moved, Sloane built the Sloane House Hotel, which stood there until the 1950s.

In 1881, Sloane sold the house to his son Thomas, who the next year married Eleutheros’ granddaughter, Sarah. Here they had two children, the only ones to live here. The couple stayed there the rest of their lives. Thomas was your typical upper-middle class person of his era: he was a lawyer, judge, dabbled in politics, served as the Firelands Historical Society’s director, and was heavily involved with his local Episcopal church. He also had a real estate business. He died in 1920 and his wife the next year.

After the latter’s death, the house was sold to Rush R. Sloan on April 11, 1879. He decided to move it a mile north on Columbus Avenue, the place where it still currently stands. He hired Jacob Beihl to oversee this project. Beihl diagramed the house, then oversaw its dismantling and reconstruction. He did such a good job only one stone was missing when the project was finished. Sloan had modifications done to the house that included a deeper basement, replacing a flat roof with a peaked one, installing central heating, and moving the servants’ quarters. On the lot from which the house was moved, Sloane built the Sloane House Hotel, which stood there until the 1950s.

In 1881, Sloane sold the house to his son Thomas, who the next year married Eleutheros’ granddaughter, Sarah. Here they had two children, the only ones to live here. The couple stayed there the rest of their lives. Thomas was your typical upper-middle class person of his era: he was a lawyer, judge, dabbled in politics, served as the Firelands Historical Society’s director, and was heavily involved with his local Episcopal church. He also had a real estate business. He died in 1920 and his wife the next year.

Upon the latter’s death, the house was sold to Judge Roy Hughes Williams and his wife, L. Verna Lockwood. Judge Williams’ claim to fame was that he empaneled the very first all female jury in Erie County on August 18, 1920—the very day the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, giving women the right to vote. Verna served on that jury, which today would be unethical if not illegal. Roy died in 1946, and Verna passed in 1950.

The final private owner of the house was Randolph Dorn and his wife, Estelle Rose. For the first time in its history, its main breadwinner wasn’t an attorney. Dorn was the CEO of Barr Rubber Products, which had moved from Lorain to Sandusky and produced a variety of product lines including toys.

The couple decided to modernize the interior, which took two years. Upon its completion, they moved in. This remodeling created a shocking contrast. On the outside the house is a Greek Rival style typical of the era in which it was built. It even has castle-like crenels outlining its roof. Go inside and suddenly your find yourself in the 1950s, all be it with many items only the wealthy could afford.

In addition to removing or shifting walls, the couple installed three chandeliers found in storage that were purchased by Jay Cooke. They also replaced nearly all the house’s wooden fireplace surrounds with stone ones. The master bathrooms were state of the art in it their day. A Steinway grand piano graced the living room. In the dining room a mural was hand painted on the wallpaper. Their formal dinnerware included dishes with real gold leaf. The kitchen had items so cutting edge that they didn’t become common for decades such as an island range top, two built-in ovens, a garbage disposal and a dishwasher. The sunroom has on its walls rubber paneling produced as a prototype by Barr Rubber Products. This is the only place in the world you can find it.

The final private owner of the house was Randolph Dorn and his wife, Estelle Rose. For the first time in its history, its main breadwinner wasn’t an attorney. Dorn was the CEO of Barr Rubber Products, which had moved from Lorain to Sandusky and produced a variety of product lines including toys.

The couple decided to modernize the interior, which took two years. Upon its completion, they moved in. This remodeling created a shocking contrast. On the outside the house is a Greek Rival style typical of the era in which it was built. It even has castle-like crenels outlining its roof. Go inside and suddenly your find yourself in the 1950s, all be it with many items only the wealthy could afford.

In addition to removing or shifting walls, the couple installed three chandeliers found in storage that were purchased by Jay Cooke. They also replaced nearly all the house’s wooden fireplace surrounds with stone ones. The master bathrooms were state of the art in it their day. A Steinway grand piano graced the living room. In the dining room a mural was hand painted on the wallpaper. Their formal dinnerware included dishes with real gold leaf. The kitchen had items so cutting edge that they didn’t become common for decades such as an island range top, two built-in ovens, a garbage disposal and a dishwasher. The sunroom has on its walls rubber paneling produced as a prototype by Barr Rubber Products. This is the only place in the world you can find it.

After moving in, the Dorns built a greenhouse from which they ran a side business, Blossom House, that sold exotic plants. Randolph didn’t get to enjoy his new home for long. He died in 1965 at the age of sixty-four. Estella, on the other land, stayed another twenty-nine years until her death in 1994. She not only bequeathed the house and everything in it to the Ohio Historical Society (now the Ohio History Connection), she threw in a $300,000 endowment for its upkeep. If the Ohio History Connection ever decides to end its time as caretaker, the property goes to the Randolph J and Estelle M Dorn Foundation. The house is managed by the Old House Guild of Sandusky.

I want to give a special thanks to site manager Ed Stout. He took time out his busy schedule to give me a personal tour via an appointment.

I want to give a special thanks to site manager Ed Stout. He took time out his busy schedule to give me a personal tour via an appointment.