DONALD THOMPSON: THE CON ARTIST WHO BECAME A GREAT PHOTOJOURNALIST

Copyright © 2019 by Mark Strecker.

Adapted from Americans in a Splintering Europe: Refugees, Missionaries and Journalists in World War I (McFarland, Copyright © 2019 by Mark Strecker.

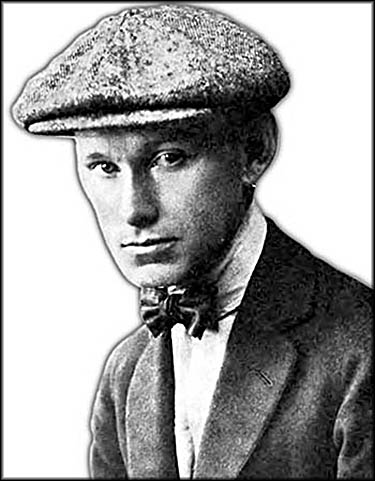

Donald Thompson

Photo from Donald Thompson in Russia

by Donald C. Thompson (1918).

Digitized by Google Books.

Modified and enhanced by Mark Strecker.

Photo from Donald Thompson in Russia

by Donald C. Thompson (1918).

Digitized by Google Books.

Modified and enhanced by Mark Strecker.

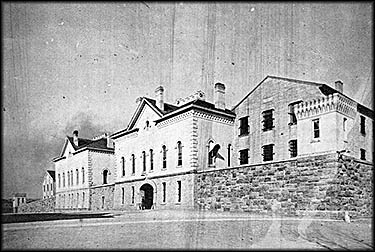

Leavenworth Prison

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

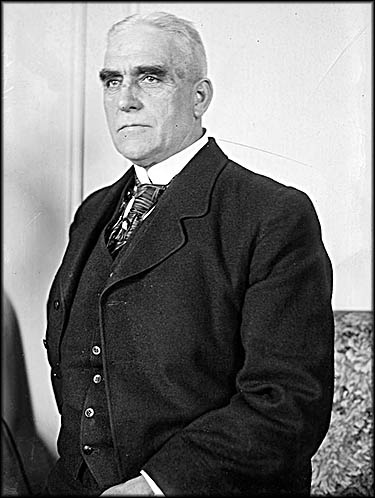

Sam Hughes

Taken between 1915 and 1920. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress.

Taken between 1915 and 1920. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress.

General John French, Head of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in Belgium and France

Taken between 1914 and 1915. Bain News Service. Library of Congress

Taken between 1914 and 1915. Bain News Service. Library of Congress

Born in Topeka, Kansas, probably on January 19, 1885, Thompson’s appearance hid an ambition and audacity unmatched by few others. A mere five four in height with an average weight of about 120 pounds, he had a clean shaven face and a “sunflower smile.” He showed an uncanny coolness when under fire. Even after suffering a major wound, he went right back to the fighting after recovering. Usually seen chewing or puffing on a cigar, when Powell first met him in Ostend, Thompson “blew into the [U.S.] Consulate … wearing an American army shirt, a pair of British officer’s riding-breeches, French puttees [a single length of cloth wrapped around each leg], and a Highlander’s forage-cap, and carrying a camera the size of a parlor phonograph.”

Thompson had begun his career as a photojournalist in 1903 when he went to work for the Topeka newspaper Capital, supplementing his income with an occasional bit of fraud. In 1909, the Secret Service arrested him in Norfolk, Virginia, for impersonating two different army officers, Lieutenants D.C. Huffman and Earl McFarland, in whose names he had written a series of bad checks across the country. Thompson had posed as the latter in Los Angeles despite the fact the genuine man was stationed in the Philippines. When caught, he confessed to all, serving two years in Leavenworth for his crimes. Upon his release on June 6, 1911, authorities arrested him the moment he walked outside the prison gates, this time for fraud he had allegedly committed in Columbus, Ohio. Imprisonment did not deter him from trying it again. In 1923, he passed bad checks in the names of naval officers. During this crime spree, he even had the audacity to pose as Franklin D. Roosevelt.33

Thompson’s experience as a confidence man would serve him well during his coverage of the war: he did not hesitate to lie, cheat or steal to get what he wanted. When the Germans offered him money to spy on their behalf, he took it, then claimed, “Their dastardly work I did not do. The money I spent in cafés in many a capital in Europe.… I am only sorry they didn’t give me more.” When asked how many languages he spoke, he replied, “Three.… English, American and Yankee.” His inability to speak any foreign tongues did not deter him from plunging alone into areas in which no one spoke English.

He was living in Montreal and working for the newspaper Cartier Centenary when the war broke out. Gambling it would present a photographer like him the chance of a lifetime, he sold off all his possessions, pawned his watch, and used the proceeds to buy three large cameras plus a ticket on a steamship, leaving him with about $15. Knowing he would need credentials, he solicited his friend Sir Sam Hughes, the Canadian minister of the militia, for letter of introduction. Hughes, born in Ontario and descended from Ulster Orangemen (militant Irish Protestants who wanted Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom), he would recruit about 40,000 army volunteers in the war’s first two years, but later come under fire for his autocratic tendencies. He tried but failed to keep the Canadian Expeditionary Force independent from the British.

Thompson brought to Europe with him both still and motion picture cameras. For the former, he always used Kodaks, possibly the Autographic model. For the latter, usually made out of wood in this era, he probably did not employ the common hand crank model but rather relied on one that used battery power. He arrived in Liverpool in August 1914 and from there made his way to London where he foolishly spent the remainder of his money by staying in the Savoy. Penniless, he nonetheless made his way to France with dubious credentials: a passport, his letter from Hughes, and card saying he belonged to the Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks. Told he could go to the front as soon as permission to do so came through, after two days he gave up waiting and headed for Paris anyway. There he met with Ambassador Herrick and from him procured an introduction to French War Office. Those working there told him he could go to the front when the British War Office gave him permission. Realizing they would never allow a photographer there, he left for it anyway, pawning his last piece of jewelry to raise the funds.

Here his skills as a con artist served him well, starting with his claim of being a captain in an unnamed branch of an unknown military service. French authorities arrested him a number of times, but his excuses usually secured his freedom. Once he told them he needed to get to the Belgian front to rescue his wife and children. One of the French officers who heard the tale, greatly moved, gave him a lift in his car. On another occasion, he presented his letter from Sir Hughes and said he needed to catch up with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, an interesting tale considering its first wave of soldiers did not sail until October 2 and would not arrive in Liverpool until October 14.

He reached the front by taking a train as far as it would go, then walked the rest of the way. At Mons, the Belgian town at which the first battle the British Expeditionary Force (BED), fought on the European continent occurred, he embedded himself with a Highland regiment. For eighteen hours he took photos and filmed them while under continuous German fire. He made his way to the French trenches and there met a lieutenant who had once arrested him. He put Thompson on a train for Amiens with guards to ensure he transferred to one in Boulogne that would go nonstop to the coast. Once there, Thompson was ordered to go straight to England.

To escape his minders, he dove through an open window into a first class compartment reserved for a Russian countess who had decided to leave Paris and return to her homeland. Just outside of Boulogne, the train stopped to allow officials from Scotland Yard to search foreign passengers for contraband. Having had his film confiscated once before, he asked the countess to hide it on her person, gambling authorities would leave her alone. She said she would if he loaned her the 1,000 francs she needed to get home. He only had 250 on his person, so he handed these over, then said he would give her the rest in American money. Having an insufficient amount of this, he threw into the bargain all his coupons from the United Cigar Stores, a chain started in New York City owned by George J. Whelan. Known for banning the placement of Indian statues in front of his stores, within his establishments men could exchange coupons for items such as fishing rods and pipe cases for themselves and cut-glass dishes and silk stockings for wives or girlfriends.

Thompson had begun his career as a photojournalist in 1903 when he went to work for the Topeka newspaper Capital, supplementing his income with an occasional bit of fraud. In 1909, the Secret Service arrested him in Norfolk, Virginia, for impersonating two different army officers, Lieutenants D.C. Huffman and Earl McFarland, in whose names he had written a series of bad checks across the country. Thompson had posed as the latter in Los Angeles despite the fact the genuine man was stationed in the Philippines. When caught, he confessed to all, serving two years in Leavenworth for his crimes. Upon his release on June 6, 1911, authorities arrested him the moment he walked outside the prison gates, this time for fraud he had allegedly committed in Columbus, Ohio. Imprisonment did not deter him from trying it again. In 1923, he passed bad checks in the names of naval officers. During this crime spree, he even had the audacity to pose as Franklin D. Roosevelt.33

Thompson’s experience as a confidence man would serve him well during his coverage of the war: he did not hesitate to lie, cheat or steal to get what he wanted. When the Germans offered him money to spy on their behalf, he took it, then claimed, “Their dastardly work I did not do. The money I spent in cafés in many a capital in Europe.… I am only sorry they didn’t give me more.” When asked how many languages he spoke, he replied, “Three.… English, American and Yankee.” His inability to speak any foreign tongues did not deter him from plunging alone into areas in which no one spoke English.

He was living in Montreal and working for the newspaper Cartier Centenary when the war broke out. Gambling it would present a photographer like him the chance of a lifetime, he sold off all his possessions, pawned his watch, and used the proceeds to buy three large cameras plus a ticket on a steamship, leaving him with about $15. Knowing he would need credentials, he solicited his friend Sir Sam Hughes, the Canadian minister of the militia, for letter of introduction. Hughes, born in Ontario and descended from Ulster Orangemen (militant Irish Protestants who wanted Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom), he would recruit about 40,000 army volunteers in the war’s first two years, but later come under fire for his autocratic tendencies. He tried but failed to keep the Canadian Expeditionary Force independent from the British.

Thompson brought to Europe with him both still and motion picture cameras. For the former, he always used Kodaks, possibly the Autographic model. For the latter, usually made out of wood in this era, he probably did not employ the common hand crank model but rather relied on one that used battery power. He arrived in Liverpool in August 1914 and from there made his way to London where he foolishly spent the remainder of his money by staying in the Savoy. Penniless, he nonetheless made his way to France with dubious credentials: a passport, his letter from Hughes, and card saying he belonged to the Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks. Told he could go to the front as soon as permission to do so came through, after two days he gave up waiting and headed for Paris anyway. There he met with Ambassador Herrick and from him procured an introduction to French War Office. Those working there told him he could go to the front when the British War Office gave him permission. Realizing they would never allow a photographer there, he left for it anyway, pawning his last piece of jewelry to raise the funds.

Here his skills as a con artist served him well, starting with his claim of being a captain in an unnamed branch of an unknown military service. French authorities arrested him a number of times, but his excuses usually secured his freedom. Once he told them he needed to get to the Belgian front to rescue his wife and children. One of the French officers who heard the tale, greatly moved, gave him a lift in his car. On another occasion, he presented his letter from Sir Hughes and said he needed to catch up with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, an interesting tale considering its first wave of soldiers did not sail until October 2 and would not arrive in Liverpool until October 14.

He reached the front by taking a train as far as it would go, then walked the rest of the way. At Mons, the Belgian town at which the first battle the British Expeditionary Force (BED), fought on the European continent occurred, he embedded himself with a Highland regiment. For eighteen hours he took photos and filmed them while under continuous German fire. He made his way to the French trenches and there met a lieutenant who had once arrested him. He put Thompson on a train for Amiens with guards to ensure he transferred to one in Boulogne that would go nonstop to the coast. Once there, Thompson was ordered to go straight to England.

To escape his minders, he dove through an open window into a first class compartment reserved for a Russian countess who had decided to leave Paris and return to her homeland. Just outside of Boulogne, the train stopped to allow officials from Scotland Yard to search foreign passengers for contraband. Having had his film confiscated once before, he asked the countess to hide it on her person, gambling authorities would leave her alone. She said she would if he loaned her the 1,000 francs she needed to get home. He only had 250 on his person, so he handed these over, then said he would give her the rest in American money. Having an insufficient amount of this, he threw into the bargain all his coupons from the United Cigar Stores, a chain started in New York City owned by George J. Whelan. Known for banning the placement of Indian statues in front of his stores, within his establishments men could exchange coupons for items such as fishing rods and pipe cases for themselves and cut-glass dishes and silk stockings for wives or girlfriends.

Ostend (The Embankment) Taken between 1890 and 1900.

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

Antwerp

Taken between 1890 and 1900. Library of Congress

Taken between 1890 and 1900. Library of Congress

Dixmude

Taken between 1910 and 1915. Bain News Service. Library of Congress.

Taken between 1910 and 1915. Bain News Service. Library of Congress.

English Fleet Off Ostend

Taken between 1914 and 1915. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

Taken between 1914 and 1915. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

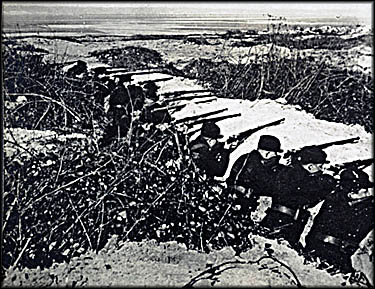

Trenches of the Allies among the Dunes and Brambles on

the Coast of Flanders.

Taken between 1914 and 1918. Keystone View Company. Library of Congress

the Coast of Flanders.

Taken between 1914 and 1918. Keystone View Company. Library of Congress

Birdseye View of a Battlefield on the Somme Front.

January 19, 1917. Central News Photo. Library of Congress.

January 19, 1917. Central News Photo. Library of Congress.

British Guns at the Battle of the Somme.

1916. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress.

1916. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress.

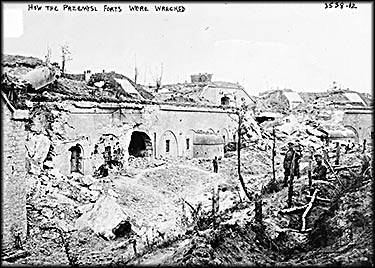

Przemysl Forts.

Taken between 1915 and 1916. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

Taken between 1915 and 1916. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

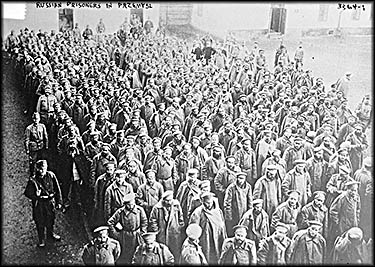

Russian Prisoners in Przemysl

Taken between 1915 and 1916. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

Taken between 1915 and 1916. Bain News Service.

Library of Congress

Turk Battery, Gallipoli

Taken between 1915 and 1916.

Library of Congress.

Taken between 1915 and 1916.

Library of Congress.

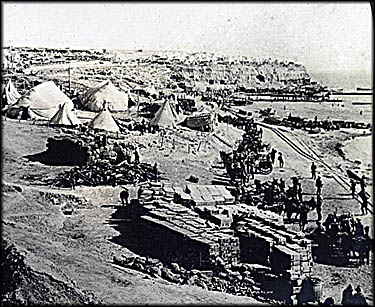

West Beach, Gallipoli: Scene

of British Landing

and of Terrible Battles

Taken between 1915 and 1918. Keystone View Company. Library of Congress.

of British Landing

and of Terrible Battles

Taken between 1915 and 1918. Keystone View Company. Library of Congress.

The police, mistaking Thompson for a spy, took him off the train and strip searched in front of a gathering crowd. Finding nothing, they allowed him to get back on. In London, he found the Russian countess at her hotel. She not only gave him his precious film, she also returned his money and coupons. He sold his work to the World and Daily Mail for $5,000.

He returned to the continent in October, this time landing in Ostend, where he met the American vice-consul. This official introduced him to Powell, who had secured a permit to embed himself with the Belgian army and who had a car he planned to take to Antwerp. Thompson talked his way into accompanying him despite the fact the Belgian army allowed no photographers. After arriving at their destination, Powell offhandedly remarked during a dinner that King Albert resided just a few doors down from their hotel at the Place de Meir. Thompson excused himself and headed there.

Although a guard stood at its entrance, he just passed him by and, once inside, got into a strange argument with a servant in which he spoke in English and the other in French. The first secretary to the minister of foreign affairs came downstairs and asked in English what Thompson wanted. He desired to chronicle German atrocities on film, which would give the Belgians irrefutable proof of this. Ten hours later he met with the king himself and, although a bit shy at first considering only a few years earlier he has shucked corn in Kansas, he told his majesty what he wanted. The king agreed, handed him a laissez-passer—an item that allowed foreign journalists to move freely about the country—and said his people would help in any way possible,

During the siege of Antwerp, Thompson appropriated an abandoned house at 74 rue de Peage and from it hung a large American flag. Several others, including a couple of journalists and the former Dutch vice-consul, stayed with him. Dubbing it “Thompson’s Fort,” he plundered the surrounding neighborhood for supplies. Fellow American journalist Horace Green stopped by and invited everyone to stay at the Queen’s Hotel, which stood along the Scheldt, but the house’s inhabitants decided to stay put. Half an hour after Green’s departure, a white-faced Thompson and the others arrived at the hotel. A shell had destroyed the top two floors of their house and burned the rest down.

Thompson sold his photos and films to a variety of newspapers, including the World, the Chicago Tribune, the Illustrated London News, and the Daily Mail. The owner of the last of these periodicals, Lord Northcliffe, hired Thompson to report from Germany. Northcliffe, whose full name amounted to quite the mouthful—Sir Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe of St. Peter-in-Thanet and Baron Northcliffe of the Isle of Thanet—owned a number of newspapers but loved the Daily Mail the most, a paper he personally edited that had a daily circulation of 900,000 when the war broke out. Despite coming from noble stock and having many titles, he grew up impoverished (at least for an aristocrat), an experience that made him embrace the working class.

Going to Germany would be dangerous for Thompson because the Germans had posted notices to apprehend him out of the mistaken belief the British military had used his photos as a source of intelligence. Northcliffe had the fake Brooklyn newspaper, the Daily Observer, printed up that included an interview with Thompson in which he said nice things about the Germans. At the border, the Germans detained, beat and incarcerated him. When his jailors searched his person and found the clipping from the Daily Observer from his billfold, they let him go, a reprieve that did not last long. A German spy working at the Daily Mail informed his handlers of the deception. While at his hotel, a chambermaid warned Thompson that German authorities had come for him, so he departed by sliding down a fire escape. He promised a local girlfriend he would elope with her in exchange for her obtaining a passport made for him by her brother. Once safely across the border, he told her he did not love her after all.

Next he went to Antwerp. The moment he got off his train, a German lieutenant arrested and took him to the German headquarters at City Hall. There this young officer admitted to having mistaken Thompson for an Englishman. Thompson received an apology. The commanding general asked him to lunch. To this he readily agreed. He told the general and several others at the meal that his wife lived in Ostend and he very much wanted to see her. They would happily motor him there. Knowing this might result in the discovery of his lie, he said he planned to stay in Antwerp for a few days before heading there. The Germans loaned him a motorcycle. Having never rode one before, he learned how to operate it on the fly, making a considerable bit of noise (and annoying the locals) while he figured it out. He went to Malines to retrieve a trunk he had left there during one of his earlier trips. All the villages between it and Brussels were “in ruins” with the dead still lying in fields.

Upon his return to Antwerp, he asked for permission to head to the coast, where he heard fighting had broken out. Refused, he dug out a letter from the vice-consul in Ostend and pretended he needed to deliver it to him as a special American envoy. Still using the motorcycle, he made his way to Bruges, showing his American passport when necessary. In Dixmude, “a quiet little town on the Yser” the Germans had taken, lost to the Belgians, then reoccupied, he convinced a German captain that he had personal permission from the Kaiser to photograph German troops. He embedded with a detachment of soldiers heading north.

He arrived just in time for the Battle of the Yser, itself a small part of what would become known as the Race for the Sea, the last great maneuver of the war on the Western Front before the stalemate. Having lost their opportunity to take Paris in a quick swoop, the Germans now made a desperate attempt to outflank French, Belgian, and British forces by heading around them to the north. To slow them down, King Albert ordered the dike gates opened in Nieuport to flood the lands to the south with seawater so as to create a natural barrier between the Germans and Belgians. The gates stayed open between October 28 to 31.

The Germans countered by opening other dikes. Not only did both sides have to contend with marshy territory, a northern gale had brought with it mist, rain and fog that prevented British battleships from getting close enough to shore to shell German forces along the coast. Across the Yser itself, both sides dug in and began flinging artillery shells at one another at close range. The fighting resulted in untold carnage. One journalist reported, “Nieuport and Dixmude are literally cities of the dead.… Shells have battered down the walls and buildings and all that either the Germans and allies may hold in occupying either post is a pile of shattered[,] crumbling ruins.”

At the coast, Thompson joined the Germans in trenches dug out of the sand into which enemy batteries and British battleships fired. He made himself a sort of cave away from the main line for added protection. At some point the Germans retreated using underground passages without Thompson realizing it. He became lost in the maze of them and did not emerge until night. Trenches along the coast such as these became the northernmost part of a system that would stretch south all the way to the Swiss border. After the Race for the Sea ended, King Albert, never captured, retired to the village of La Panne, one of the few remaining parcels of Belgium soil under his control.

He returned to the continent in October, this time landing in Ostend, where he met the American vice-consul. This official introduced him to Powell, who had secured a permit to embed himself with the Belgian army and who had a car he planned to take to Antwerp. Thompson talked his way into accompanying him despite the fact the Belgian army allowed no photographers. After arriving at their destination, Powell offhandedly remarked during a dinner that King Albert resided just a few doors down from their hotel at the Place de Meir. Thompson excused himself and headed there.

Although a guard stood at its entrance, he just passed him by and, once inside, got into a strange argument with a servant in which he spoke in English and the other in French. The first secretary to the minister of foreign affairs came downstairs and asked in English what Thompson wanted. He desired to chronicle German atrocities on film, which would give the Belgians irrefutable proof of this. Ten hours later he met with the king himself and, although a bit shy at first considering only a few years earlier he has shucked corn in Kansas, he told his majesty what he wanted. The king agreed, handed him a laissez-passer—an item that allowed foreign journalists to move freely about the country—and said his people would help in any way possible,

During the siege of Antwerp, Thompson appropriated an abandoned house at 74 rue de Peage and from it hung a large American flag. Several others, including a couple of journalists and the former Dutch vice-consul, stayed with him. Dubbing it “Thompson’s Fort,” he plundered the surrounding neighborhood for supplies. Fellow American journalist Horace Green stopped by and invited everyone to stay at the Queen’s Hotel, which stood along the Scheldt, but the house’s inhabitants decided to stay put. Half an hour after Green’s departure, a white-faced Thompson and the others arrived at the hotel. A shell had destroyed the top two floors of their house and burned the rest down.

Thompson sold his photos and films to a variety of newspapers, including the World, the Chicago Tribune, the Illustrated London News, and the Daily Mail. The owner of the last of these periodicals, Lord Northcliffe, hired Thompson to report from Germany. Northcliffe, whose full name amounted to quite the mouthful—Sir Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe of St. Peter-in-Thanet and Baron Northcliffe of the Isle of Thanet—owned a number of newspapers but loved the Daily Mail the most, a paper he personally edited that had a daily circulation of 900,000 when the war broke out. Despite coming from noble stock and having many titles, he grew up impoverished (at least for an aristocrat), an experience that made him embrace the working class.

Going to Germany would be dangerous for Thompson because the Germans had posted notices to apprehend him out of the mistaken belief the British military had used his photos as a source of intelligence. Northcliffe had the fake Brooklyn newspaper, the Daily Observer, printed up that included an interview with Thompson in which he said nice things about the Germans. At the border, the Germans detained, beat and incarcerated him. When his jailors searched his person and found the clipping from the Daily Observer from his billfold, they let him go, a reprieve that did not last long. A German spy working at the Daily Mail informed his handlers of the deception. While at his hotel, a chambermaid warned Thompson that German authorities had come for him, so he departed by sliding down a fire escape. He promised a local girlfriend he would elope with her in exchange for her obtaining a passport made for him by her brother. Once safely across the border, he told her he did not love her after all.

Next he went to Antwerp. The moment he got off his train, a German lieutenant arrested and took him to the German headquarters at City Hall. There this young officer admitted to having mistaken Thompson for an Englishman. Thompson received an apology. The commanding general asked him to lunch. To this he readily agreed. He told the general and several others at the meal that his wife lived in Ostend and he very much wanted to see her. They would happily motor him there. Knowing this might result in the discovery of his lie, he said he planned to stay in Antwerp for a few days before heading there. The Germans loaned him a motorcycle. Having never rode one before, he learned how to operate it on the fly, making a considerable bit of noise (and annoying the locals) while he figured it out. He went to Malines to retrieve a trunk he had left there during one of his earlier trips. All the villages between it and Brussels were “in ruins” with the dead still lying in fields.

Upon his return to Antwerp, he asked for permission to head to the coast, where he heard fighting had broken out. Refused, he dug out a letter from the vice-consul in Ostend and pretended he needed to deliver it to him as a special American envoy. Still using the motorcycle, he made his way to Bruges, showing his American passport when necessary. In Dixmude, “a quiet little town on the Yser” the Germans had taken, lost to the Belgians, then reoccupied, he convinced a German captain that he had personal permission from the Kaiser to photograph German troops. He embedded with a detachment of soldiers heading north.

He arrived just in time for the Battle of the Yser, itself a small part of what would become known as the Race for the Sea, the last great maneuver of the war on the Western Front before the stalemate. Having lost their opportunity to take Paris in a quick swoop, the Germans now made a desperate attempt to outflank French, Belgian, and British forces by heading around them to the north. To slow them down, King Albert ordered the dike gates opened in Nieuport to flood the lands to the south with seawater so as to create a natural barrier between the Germans and Belgians. The gates stayed open between October 28 to 31.

The Germans countered by opening other dikes. Not only did both sides have to contend with marshy territory, a northern gale had brought with it mist, rain and fog that prevented British battleships from getting close enough to shore to shell German forces along the coast. Across the Yser itself, both sides dug in and began flinging artillery shells at one another at close range. The fighting resulted in untold carnage. One journalist reported, “Nieuport and Dixmude are literally cities of the dead.… Shells have battered down the walls and buildings and all that either the Germans and allies may hold in occupying either post is a pile of shattered[,] crumbling ruins.”

At the coast, Thompson joined the Germans in trenches dug out of the sand into which enemy batteries and British battleships fired. He made himself a sort of cave away from the main line for added protection. At some point the Germans retreated using underground passages without Thompson realizing it. He became lost in the maze of them and did not emerge until night. Trenches along the coast such as these became the northernmost part of a system that would stretch south all the way to the Swiss border. After the Race for the Sea ended, King Albert, never captured, retired to the village of La Panne, one of the few remaining parcels of Belgium soil under his control.

Thompson returned to Dixmude. While dining with General Boehm and some of his officers here, a British shell hit the house in which they ate. Two inhabitants died instantly and another later succumbed to his wounds. Wooden splinters pierced Thompson’s back and nose while other flying debris bruised his body. He awoke in a field hospital alongside wounded Germans, then returned to Antwerp in an ammunition cart. He thought he had lost his nose because he could not feel it, but it remained. He went to London to recuperate, then returned to America in mid-November, arriving in Topeka in January 1915. Here he showed about 1,000 feet of his film at the Novelty Theater.

He received an invitation from Robert R. McCormick, publisher of the Chicago Tribune as well as one of its war correspondents, to cover the Russian front after its government invited him to do so. McCormick also owned the New York Daily News and Washington Times-Herald, but of these papers, the Tribune, started in 1847, did the best. It reached a circulation of 410,000 in 1918, an impressive feat considering McCormick did not get into the newspaper business until 1910 when he and partner, Joseph Medill Patterson, took it over rather than allow a rival to buy it out. McCormick and Thompson headed for Russia in February 1915.

One of the fiercest battles these two men covered was at the Austro-Hungarian fortress city of Przemysl. It was located in the province of the largely unindustrialized Galicia, an area that had once belonged to the kingdom of Poland before it ceased to exist after Russia, Prussia, and the Austrian Empire carved that nation up for themselves between 1772 and 1795. The Russians had to take Przemysl if they wanted to successfully invade Austria-Hungary, and to that end attacked it on September 26, 1914. Capturing it on October 10, they abandoned it several weeks later. Undaunted, they returned and began a siege at the beginning of November.

This city of 50,000, founded in the eighth century and inhabited mainly by ethnic Poles, stood along the river San and served as the seats for both Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox bishops. On November 4, the Austro-Hungarian army garrison ejected the city’s civilian population, although many returned for lack of anywhere else to go, leaving the city with about 18,000 civilians and 127,000 soldiers. The Russians laid siege for six months, attacking from all sides and shooting down any planes attempting to bring in supplies. Not an animal save for the horses that belonged to army officers remained in sight.

The Austrians reluctantly surrendered on March 22, 1915, only doing so when their garrison threatened to mutiny because its men had grown tired of starving and suffering from disease. The Russians offered generous terms: officers received parole, enlisted men would not be sent to Siberia, the wounded could return to Austria, and civilians could either stay or go as they pleased. Some footage of this struggle later appeared in Thompson’s Tribune-produced 1915 movie With the Russians at the Front.

After his tour of Russia, during which he met the notorious Rasputin, Thompson headed to Bucharest. The next day—May 23, 1915—neutral Italy joined the Allies in exchange for a promise of new territories carved out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Thompson moved on to Bulgaria where he was arrested and jailed for a week for reasons he claimed to never understand. It ejected him into Serbia, where he purportedly filmed Austro-Hungarian atrocities against the Serbs, although whether he saw these firsthand or just heard about them remains questionable. Certainly such atrocities did occur. George Macaulay Trevelyan, an American historian, visited Serbia in the opening days of the war. He reported that in the middle of August 1914 near the city of Sabac, the Austro-Hungarian army killed about 3,000 civilians, including burning some to death, and forced millions more into flight.

Next Thompson headed to Istanbul (then called Constantinople Westerners) where he visited the nearby Przemysl front, a peninsula at the entrance of the narrow Dardanelles Strait along which Ottoman fortifications prevented both British and Russian navies from passing, blocking access to the Black Sea. After attempts to destroy its fortifications from sea failed, Winston Churchill, then the First Lord of the Admiralty, concocted a plan for an amphibious landing on the beaches of Gallipoli that would take possession of the entire Strait and from there Istanbul itself. Begun on April 25, 1915, the operation failed spectacularly despite an influx of reinforcements in August. The Allies began withdrawing from this disaster in December.58

In 1916, Thompson went to France as an official cinematographer of that government and there filmed the first Battle of the Somme, an area in which virtually no fighting had occurred since 1914. This lack of activity had given the Germans time to dig advanced trenches complete with well-placed machine guns and other implements of death. General Douglas Haig of the British army came up with the idea of bombarding German positions with a weeklong artillery barrage of over a million shells that would, he believed, kill all the Germans, allowing the British army to move into the open country beyond.59

He received an invitation from Robert R. McCormick, publisher of the Chicago Tribune as well as one of its war correspondents, to cover the Russian front after its government invited him to do so. McCormick also owned the New York Daily News and Washington Times-Herald, but of these papers, the Tribune, started in 1847, did the best. It reached a circulation of 410,000 in 1918, an impressive feat considering McCormick did not get into the newspaper business until 1910 when he and partner, Joseph Medill Patterson, took it over rather than allow a rival to buy it out. McCormick and Thompson headed for Russia in February 1915.

One of the fiercest battles these two men covered was at the Austro-Hungarian fortress city of Przemysl. It was located in the province of the largely unindustrialized Galicia, an area that had once belonged to the kingdom of Poland before it ceased to exist after Russia, Prussia, and the Austrian Empire carved that nation up for themselves between 1772 and 1795. The Russians had to take Przemysl if they wanted to successfully invade Austria-Hungary, and to that end attacked it on September 26, 1914. Capturing it on October 10, they abandoned it several weeks later. Undaunted, they returned and began a siege at the beginning of November.

This city of 50,000, founded in the eighth century and inhabited mainly by ethnic Poles, stood along the river San and served as the seats for both Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox bishops. On November 4, the Austro-Hungarian army garrison ejected the city’s civilian population, although many returned for lack of anywhere else to go, leaving the city with about 18,000 civilians and 127,000 soldiers. The Russians laid siege for six months, attacking from all sides and shooting down any planes attempting to bring in supplies. Not an animal save for the horses that belonged to army officers remained in sight.

The Austrians reluctantly surrendered on March 22, 1915, only doing so when their garrison threatened to mutiny because its men had grown tired of starving and suffering from disease. The Russians offered generous terms: officers received parole, enlisted men would not be sent to Siberia, the wounded could return to Austria, and civilians could either stay or go as they pleased. Some footage of this struggle later appeared in Thompson’s Tribune-produced 1915 movie With the Russians at the Front.

After his tour of Russia, during which he met the notorious Rasputin, Thompson headed to Bucharest. The next day—May 23, 1915—neutral Italy joined the Allies in exchange for a promise of new territories carved out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Thompson moved on to Bulgaria where he was arrested and jailed for a week for reasons he claimed to never understand. It ejected him into Serbia, where he purportedly filmed Austro-Hungarian atrocities against the Serbs, although whether he saw these firsthand or just heard about them remains questionable. Certainly such atrocities did occur. George Macaulay Trevelyan, an American historian, visited Serbia in the opening days of the war. He reported that in the middle of August 1914 near the city of Sabac, the Austro-Hungarian army killed about 3,000 civilians, including burning some to death, and forced millions more into flight.

Next Thompson headed to Istanbul (then called Constantinople Westerners) where he visited the nearby Przemysl front, a peninsula at the entrance of the narrow Dardanelles Strait along which Ottoman fortifications prevented both British and Russian navies from passing, blocking access to the Black Sea. After attempts to destroy its fortifications from sea failed, Winston Churchill, then the First Lord of the Admiralty, concocted a plan for an amphibious landing on the beaches of Gallipoli that would take possession of the entire Strait and from there Istanbul itself. Begun on April 25, 1915, the operation failed spectacularly despite an influx of reinforcements in August. The Allies began withdrawing from this disaster in December.58

In 1916, Thompson went to France as an official cinematographer of that government and there filmed the first Battle of the Somme, an area in which virtually no fighting had occurred since 1914. This lack of activity had given the Germans time to dig advanced trenches complete with well-placed machine guns and other implements of death. General Douglas Haig of the British army came up with the idea of bombarding German positions with a weeklong artillery barrage of over a million shells that would, he believed, kill all the Germans, allowing the British army to move into the open country beyond.59

None of the armies on the Western Front wanted anyone photographing or filming the fighting for fear it would destroy morale among the civilians at home. Those few allowed in the lines had to submit their images to the censors who decided which photographs the public could see. Few journalists defied this restriction for fear of losing their jobs or facing arrest. Getting uncensored images out of the warzone required much nerve and a good dollop of guile, two traits exhibited with much gusto by the American photographer and filmmaker Donald C. Thompson.

In mid-May German airplanes flying overhead saw Haig’s preparations for a massive offensive, and although the German General Staff had no idea when it would begin, it nonetheless began preparing. When the Allies began setting up large artillery pieces on June 22, the Germans knew the attack would come soon. Before sending their troops “over the top” into no man’s land, the Allies fired off a barrage of poison gas. Neither this nor the weeklong bombardment did any good. Of the 100,000 men on the Allied side who attacked that first day, 20,000 died and another 40,000 returned wounded. The Allies managed to take some front line trenches and forced the Germans to pull back from a few French villages, but beyond that no other gains occurred. Thompson became a casualty of the battle as well: he received a cracked skull.

He included some the footage he had taken in his 1916 documentary War As It Really Is, which can be seen in full here. Its title is deceptive considering it showed nothing very little real combat, possibly because the French supposedly censored about 70 percent of what he had filmed. It also included parts of the 1914 Battle of Yser in Belgium. For most of it, one sees little but troop movements, shots of generals, and a spectacular view of the battlefield from 10,000 feet above in an airplane. The sixth and seventh reels show actual fighting, although the shots of the dead at the film’s end are strictly stills. Despite being a sanitized version of events, it was a box office hit.

It showed abandoned German trenches, an attack from enemy artillery while in a trench at night, and, most interesting, sappers in Yser mining underground to reach the German trenches. Although the trenches of both sides zigzagged to make it harder for shells or grenades to easily penetrate them from above, this did not lessen their vulnerability to miners digging beneath where they placed massive amounts of explosives.

Thompson’s adventures in the war did not end here. In 1917 he went to Petrograd (St. Petersburg), then the capital of tsarist Russia, where he witnessed the February Revolution that deposed Tsar Nicolas II. This was the precursor of the October Revolution later that year during which the Bolsheviks took over the country via a military coup. This you can read about in Chapter 4 of Americans in Splintering Europe: Refugees, Missionaries and Journalists in World War I (McFarland), available here. And if you decide you would like to read it but are not inclined to purchase itself yourself, please ask you local library to do so.🕜

He included some the footage he had taken in his 1916 documentary War As It Really Is, which can be seen in full here. Its title is deceptive considering it showed nothing very little real combat, possibly because the French supposedly censored about 70 percent of what he had filmed. It also included parts of the 1914 Battle of Yser in Belgium. For most of it, one sees little but troop movements, shots of generals, and a spectacular view of the battlefield from 10,000 feet above in an airplane. The sixth and seventh reels show actual fighting, although the shots of the dead at the film’s end are strictly stills. Despite being a sanitized version of events, it was a box office hit.

It showed abandoned German trenches, an attack from enemy artillery while in a trench at night, and, most interesting, sappers in Yser mining underground to reach the German trenches. Although the trenches of both sides zigzagged to make it harder for shells or grenades to easily penetrate them from above, this did not lessen their vulnerability to miners digging beneath where they placed massive amounts of explosives.

Thompson’s adventures in the war did not end here. In 1917 he went to Petrograd (St. Petersburg), then the capital of tsarist Russia, where he witnessed the February Revolution that deposed Tsar Nicolas II. This was the precursor of the October Revolution later that year during which the Bolsheviks took over the country via a military coup. This you can read about in Chapter 4 of Americans in Splintering Europe: Refugees, Missionaries and Journalists in World War I (McFarland), available here. And if you decide you would like to read it but are not inclined to purchase itself yourself, please ask you local library to do so.🕜