Follett House

Many historical homes that have since become museums are named after their original inhabitants, and the Follett House Museum is no exception. Oran Follett was born in Gorham, New York, on September 4, 1798. His early life was shaped by the precarious health of his father, Frederick, who at the age of seventeen had been stabbed nine times, shot, then scalped during the Wyoming Massacre on July 3, 1778. Women at a nearby fort nursed him back to health, such as that was, but a terrible scar covered his head and never again was he seen without a black skullcap.

When he died in 1804, Oran’s mother married again. To escape his despised stepfather, Follett ran away at the age of eleven and became an apprentice, or “printer’s devil,” in Canandaigua, New York. At the outbreak of the War of 1812, he joined the navy operating on Lake Ontario. He became a “powder monkey”—one who fetched the black powder for cannons and other firearms from the magazine—on the sloop Jones. During his time serving on this vessel he supposedly overheard Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry (whose rank “commodore” was purely honorary) mention that Sandusky Bay was the best harbor in Lake Erie and maybe even all the Great Lakes, so surely any town started there would have a great future.

Oran returned to the printer’s shop in Canandaigua after the war, but by 1817 he had moved to Rochester as a newspaper editor. In 1819 he started his own newspaper in Batavia. Two years later he married Nancy Filer. Interested in politics, he was elected to the New York State Legislature in 1823 and during his tenure there nominated John Quincy Adams for president. Always on the move, he relocated to Buffalo in 1826 where he was one of the Buffalo Journal’s owners.

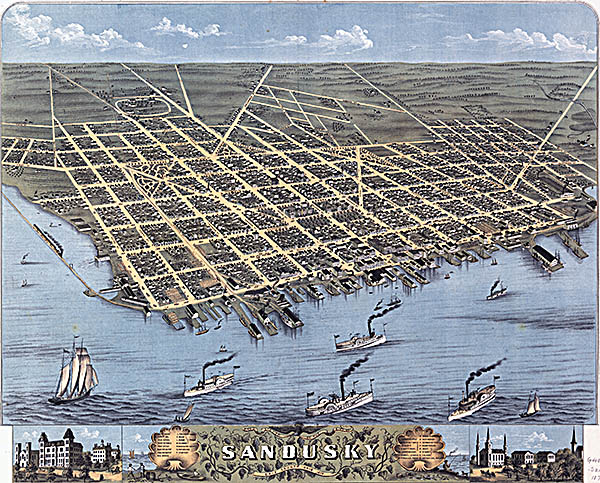

In 1830 Nancy died, leaving him with a son and three daughters. Two years later he married Elizabeth Gill Ward, whose personal history was similar to his own. After her father died, she and her mother were left destitute and forced to live with her older brother, who treated the two like servants. Terrible her brother may have been, but it was because of his contact with Oran that she met him. She would bear him two more children. The Follett family relocated to Sandusky, a town whose streets were laid out by Hector Kilbourne in the shape of the square and compass symbol used by the Masons. In 1835 construction the new family home began, which was ready in 1837.

Oran made most of his fortune as a publisher. In 1860, for example, he published the Lincoln-Douglas debates under the title Political Debates Between Hon. Abraham Lincoln and Hon. Stephen A. Douglas, in the Celebrated Campaign of 1858 in Illinois; Including the Preceding Speeches of Each, at Chicago, Springfield, etc. The 19th Century Rare Books & Photograph’s website listed a first edition of the work at $7,000 when I accessed it on August 4, 2019. After the implosion of the Whigs, Oran joined and became an enthusiastic supporter of the Republican Party. He supposedly urged President Lincoln to fire the useless General George McClellan, a notorious procrastinator who refused to fight any battle he wasn’t guaranteed to win.

Oran returned to the printer’s shop in Canandaigua after the war, but by 1817 he had moved to Rochester as a newspaper editor. In 1819 he started his own newspaper in Batavia. Two years later he married Nancy Filer. Interested in politics, he was elected to the New York State Legislature in 1823 and during his tenure there nominated John Quincy Adams for president. Always on the move, he relocated to Buffalo in 1826 where he was one of the Buffalo Journal’s owners.

In 1830 Nancy died, leaving him with a son and three daughters. Two years later he married Elizabeth Gill Ward, whose personal history was similar to his own. After her father died, she and her mother were left destitute and forced to live with her older brother, who treated the two like servants. Terrible her brother may have been, but it was because of his contact with Oran that she met him. She would bear him two more children. The Follett family relocated to Sandusky, a town whose streets were laid out by Hector Kilbourne in the shape of the square and compass symbol used by the Masons. In 1835 construction the new family home began, which was ready in 1837.

Oran made most of his fortune as a publisher. In 1860, for example, he published the Lincoln-Douglas debates under the title Political Debates Between Hon. Abraham Lincoln and Hon. Stephen A. Douglas, in the Celebrated Campaign of 1858 in Illinois; Including the Preceding Speeches of Each, at Chicago, Springfield, etc. The 19th Century Rare Books & Photograph’s website listed a first edition of the work at $7,000 when I accessed it on August 4, 2019. After the implosion of the Whigs, Oran joined and became an enthusiastic supporter of the Republican Party. He supposedly urged President Lincoln to fire the useless General George McClellan, a notorious procrastinator who refused to fight any battle he wasn’t guaranteed to win.

Follett House Museum

Inside Follett House

View from the Widow's Walk

Piano

Silver Service

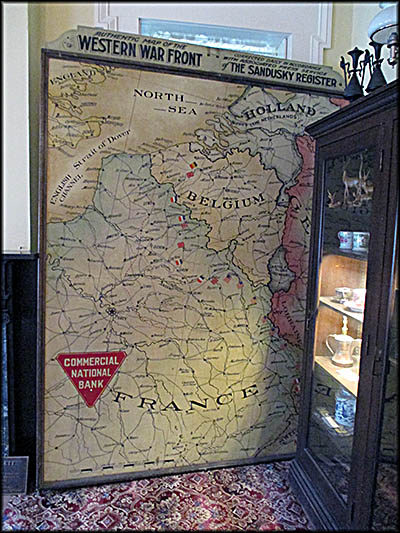

Map of Western Front During WWI

Doll Collection

Photos of African Americans from Sandusky

Creepy Statue of Punch

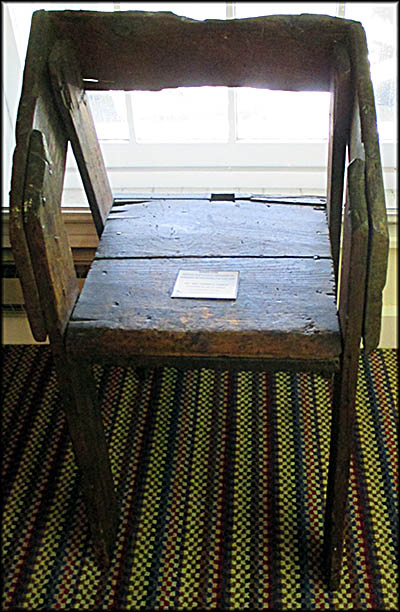

This barber's chair was used by POWs at the Civil War prison camp on Johnson's Island.

Although Oran opposed slavery, he wasn’t willing to break the law that forbade aiding escaped slaves. Elizabeth had no such qualms and hid them in their house. Oran looked the other way. A keen gardener, she was beloved in Sandusky because during terrible outbreaks of cholera and smallpox she tended to the sick. When the Civil War broke out, she rolled bandages for the troops. She died in 1878 from a hernia, likely the result of the restrictive corsets worn by upper class women such as herself. According to Mel Davies’ article “Corsets and Conception: Fashion and Demographic Trends in the Nineteenth Century” that appeared in the journal Comparative Studies in Society and History, wearing a corset long term was known to cause a variety of medical issues and it’s just as well it’s in the dustbin of history.

At the house’s top is a widow’s walk, something I’ve always wanted to climb onto but never had the opportunity to do so until here. Widow’s walks, which protrude above the roof, have a surprisingly murky history. Wealthy sea captains were known to have them included in the houses built along the waterfront. Tradition says they were there for the wives of seamen so they could watch for their husbands’ ships to come in. Another theory is that they were meant to simulate a crow’s nest or the feeling of standing on a ship’s quarterdeck. A more practical theory says they were there as a place where one could more readily fight roof fires, always a danger in the age of chimneys.

The widow’s walk atop the Follett House offers a spectacular view of Sandusky and Lake Erie. The sight of the latter brought back one of my earliest clear childhood memories. I remember my dad driving us down to Downtown Sandusky in the winter and seeing enormous activity on Lake Erie’s frozen surface, including fishing, ice boats, and skaters. My grandmother told me that my grandfather once drove her out on to the ice, which she found a terrifying experience. These days the lake rarely freezes and even when it does, such scenes no longer exist. Nor does the Sandusky’s ice harvesting industry.

This was at its largest between 1875 and 1895, earning Sandusky the nickname “Ice Capital of the Great Lakes.” Its ice harvesters, which included the Sandusky Ice Company, stored about 250,000 tons of ice in Sandusky’s fifty or so icehouses. One year the harvest reached 400,000 tons. Much of it was sold locally, but some of it went as far as Cincinnati. Although Lake Erie is at present an unappetizing mess of pollution and invasive species, in the nineteenth century its waters produced what some considered to be the best quality ice found in the United States. At its peak, ice harvesting on Lake Erie gave employment to about 2,000 men, many of whom were farmers who spent their off season doing this.

American ice harvesting on ponds had always been done on small scale, mostly by farmers. It was Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth of Boston who made it possible to transform into a big industry. The manager of the family-owned Fresh Pond Hotel, he invented the ice cutter, or ice plow, that when hooked to a horse or two made cutting ice blocks a lot easier. Soon he sold his invention exclusively to Frederic Tudor, the man who industrialized ice harvesting and became known as the “Ice King.” He exported ice all over the world. By 1856 the United States as a whole exported 146,000 ton of the stuff as far afield as China, Australia, and Calcutta, India.

The widow’s walk atop the Follett House offers a spectacular view of Sandusky and Lake Erie. The sight of the latter brought back one of my earliest clear childhood memories. I remember my dad driving us down to Downtown Sandusky in the winter and seeing enormous activity on Lake Erie’s frozen surface, including fishing, ice boats, and skaters. My grandmother told me that my grandfather once drove her out on to the ice, which she found a terrifying experience. These days the lake rarely freezes and even when it does, such scenes no longer exist. Nor does the Sandusky’s ice harvesting industry.

This was at its largest between 1875 and 1895, earning Sandusky the nickname “Ice Capital of the Great Lakes.” Its ice harvesters, which included the Sandusky Ice Company, stored about 250,000 tons of ice in Sandusky’s fifty or so icehouses. One year the harvest reached 400,000 tons. Much of it was sold locally, but some of it went as far as Cincinnati. Although Lake Erie is at present an unappetizing mess of pollution and invasive species, in the nineteenth century its waters produced what some considered to be the best quality ice found in the United States. At its peak, ice harvesting on Lake Erie gave employment to about 2,000 men, many of whom were farmers who spent their off season doing this.

American ice harvesting on ponds had always been done on small scale, mostly by farmers. It was Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth of Boston who made it possible to transform into a big industry. The manager of the family-owned Fresh Pond Hotel, he invented the ice cutter, or ice plow, that when hooked to a horse or two made cutting ice blocks a lot easier. Soon he sold his invention exclusively to Frederic Tudor, the man who industrialized ice harvesting and became known as the “Ice King.” He exported ice all over the world. By 1856 the United States as a whole exported 146,000 ton of the stuff as far afield as China, Australia, and Calcutta, India.

Tudor created demand for his product by convincing Americans they ought to put ice in their alcoholic beverages, which soon spread to less potent drinks and explains why we Americans like ice in our soft drinks. In the early 1860s meatpackers began experimenting with shipping their product packed with ice to better preserve it. Refrigeration using ice blocks changed the way Americans consumed food. When stored in warehouses filled with ice, seasonal items such as apples could be preserved and sold year-round. Into homes came the icebox so people could preserve their own food longer. To this day my uncle calls any refrigerator he sees an icebox because as a child that’s what he had.

Ice harvesting met its doom with arrival of artificial refrigeration, which has its origins in 1840s Florida. Here Doctor John Gorrie of Apalachicola needed a way to cool sick patients and found ice too expensive for that purpose. In 1849 he patented an icemaking machine that he demonstrated in 1850. The trouble was it didn’t work well, mostly because of its shoddy parts.

Over a period of about forty years starting in 1920, modern refrigeration and icemaking replaced ice harvesting. One reason for the long transition is that early electric refrigerators weren’t all that reliable. Aside from being noisy and needing quite a bit of maintenance, they tended to leak. It took research from industrial giants General Electric and General Motors—who bought the struggling company Guardian Frigerator Company in 1915 and renamed it Frigidaire—to sort these problems out, which they did around 1930. But in the midst of the Great Depression no one had money for such a luxury item, presuming one had access to an electrical grid in the first place. It wasn’t until the New Deal’s rural electrification effort and the end of the World War II that the refrigerator became a household necessity.

The museum has changing exhibits, and when I visited, the one on display was “Let Women of Ohio Vote: The Fight for Woman’s Suffrage in Erie County, 1910–1920.” Women first organized at a national level to obtain the right to vote in Seneca Falls, New York, at a meeting organized by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton that was held on July 19 and 20, 1848. Women in the movement had become frustrated at being excluded from official gatherings such as the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London. The Seneca Falls meeting, which included a few men, produced the “Declaration of Sentiments” that pointed out that a woman in the United States had no legal right to vote, keep their wages, or own property. Women lacked equal opportunity for employment and had little recourse in divorces.

Ice harvesting met its doom with arrival of artificial refrigeration, which has its origins in 1840s Florida. Here Doctor John Gorrie of Apalachicola needed a way to cool sick patients and found ice too expensive for that purpose. In 1849 he patented an icemaking machine that he demonstrated in 1850. The trouble was it didn’t work well, mostly because of its shoddy parts.

Over a period of about forty years starting in 1920, modern refrigeration and icemaking replaced ice harvesting. One reason for the long transition is that early electric refrigerators weren’t all that reliable. Aside from being noisy and needing quite a bit of maintenance, they tended to leak. It took research from industrial giants General Electric and General Motors—who bought the struggling company Guardian Frigerator Company in 1915 and renamed it Frigidaire—to sort these problems out, which they did around 1930. But in the midst of the Great Depression no one had money for such a luxury item, presuming one had access to an electrical grid in the first place. It wasn’t until the New Deal’s rural electrification effort and the end of the World War II that the refrigerator became a household necessity.

The museum has changing exhibits, and when I visited, the one on display was “Let Women of Ohio Vote: The Fight for Woman’s Suffrage in Erie County, 1910–1920.” Women first organized at a national level to obtain the right to vote in Seneca Falls, New York, at a meeting organized by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton that was held on July 19 and 20, 1848. Women in the movement had become frustrated at being excluded from official gatherings such as the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London. The Seneca Falls meeting, which included a few men, produced the “Declaration of Sentiments” that pointed out that a woman in the United States had no legal right to vote, keep their wages, or own property. Women lacked equal opportunity for employment and had little recourse in divorces.

In the early 1900s, Ohio voters decided the state constitution needed to be updated. At the Ohio Constitutional Convention of 1912, one of the proposed amendments gave women the right to vote. Erie County’s single delegate, Judge E.B. King, voted against it with the excuse that most women didn’t want that right. He based that decision on his “experience,” meaning he had probably met more women who opposed it than favored it, an inaccurate way to survey the overall desire of a population. The amendment got onto the ballot but lost by 87,000 votes. In Sandusky, 694 yoted yes and 1,603 no, though it was much closer in Erie County, which had 1,120 for and 1,258 against. In 1914 Amendment 3, which would give women in Ohio the right to vote, appeared on the Ohio ballot, but it, too, lost.

Undaunted, women in Sandusky agitated for this right at the city level. In 1917, the Sandusky City Council voted 3–2 in favor of drawing up an ordinance that would give women over the age of twenty-one the right to vote in city elections. The Council unanimously approved it for the citywide ballot, but men refused to give up their monopoly on voting and it lost by 1,000 votes. That year women’s suffrage was again voted down at the state level.

Upon taking office in 1913, women began to increase pressure on President Woodrow Wilson to grant voting rights at a national level. But being by inclination and birth a Southerner, he had no more an enlightened view about women’s equality than he did about the status of African-Americans. After his election, he insisted the vote for women must be decided at the state level. For many years the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA), established in 1890, had been trying just that. Then one of its members, Alice Paul, went to England and there met radical feminist leaders such as Sylvia Pankhurst. Upon her return home, Paul convinced the NAWSA to hold a massive parade in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 1913, the day before Wilson’s inauguration. Five thousand women wearing white robes marched up Pennsylvania Avenue that day. Many of the spectators became hostile. Stones and curses were tossed at the marchers and police did nothing to protect them.

Undaunted, women in Sandusky agitated for this right at the city level. In 1917, the Sandusky City Council voted 3–2 in favor of drawing up an ordinance that would give women over the age of twenty-one the right to vote in city elections. The Council unanimously approved it for the citywide ballot, but men refused to give up their monopoly on voting and it lost by 1,000 votes. That year women’s suffrage was again voted down at the state level.

Upon taking office in 1913, women began to increase pressure on President Woodrow Wilson to grant voting rights at a national level. But being by inclination and birth a Southerner, he had no more an enlightened view about women’s equality than he did about the status of African-Americans. After his election, he insisted the vote for women must be decided at the state level. For many years the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA), established in 1890, had been trying just that. Then one of its members, Alice Paul, went to England and there met radical feminist leaders such as Sylvia Pankhurst. Upon her return home, Paul convinced the NAWSA to hold a massive parade in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 1913, the day before Wilson’s inauguration. Five thousand women wearing white robes marched up Pennsylvania Avenue that day. Many of the spectators became hostile. Stones and curses were tossed at the marchers and police did nothing to protect them.

The publicity induced Wilson to meet with them, though nothing came of that. Wilson finally changed his mind during the negotiations formally ending World War I in Versailles where he argued for democracy for all. He also saw how well women had replaced men at their jobs during the war, and that, too, probably swayed his position. On May 20, 1919, he announced his support for the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which would give women in all states the right to vote. Introduced in 1848, it had taken forty-one years to get anywhere. Within a few weeks both the House and Senate voted for it. Next it needed ratification by thirty-six states to become a Constitutional amendment. Despite its previous and repeated opposition to give women the right to vote, Ohio became the fifth state to ratify. The last one was Tennessee on August 18, 1920. Eight days later Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby declared it the Nineteenth Amendment.

One of the more surprising artifacts on display at the museum was a zinc statue of the Shakespearean character Puck from A Midsummer’s Night Dream. Designed by sculptor Casper Buberl, it was a mass-produced item made by the William Demuth Company of New York and patented in 1881. The one in the Follett House stood in the window of the Dietz & Mischler Cigar Store from 1895 to 1918. In the 1920s it made its way to the Weir Brothers Scrap Yard from which it was found and mounted on top of Charlie Hoffman’s ice cream stand. For seventy-three years Ritter Cigar Factory and Store displayed its own sculpture, Punch, which had been carved from a spar broken off a ship docked in New York and brought back to Sandusky by the store’s owner, Henry Ritter. Although it stood outside, it was brought in each night, which probably explains its longevity.

Hanging on one of the museum’s walls is a decaying Confederate flag that once belonged to Brigadier General Felix K. Zollicoffer from Tennessee. Union surgeon Doctor Robert R. McMeens “captured” it in July 1861. According to a museum information sign, he took it from “an abandoned Confederate hospital tent near Huttonsville, West Virginia.” Just over a year later McMeens died of an unnamed disease near Perryville, Kentucky, but his prize made its way north.

The museum has some of its artifacts from the Civil War prison camp on nearby Johnson’s Island that includes a pair of cast iron stove doors, a barber chair made by a prisoner, and a civilian pass to get into the prison. Possibly the most precious item is a small book published in 1872 containing a poem written by one of the prison’s former inmates, Irl Hicks. Its title, The Prisoner’s Farewell to Johnson’s Island: Or, Valedictory Address to the Young Men’s Christian Association of Johnson’s Island, Ohio: A Poem, is also a synopsis of its content. Hicks recited it for the first time at the camp’s last Young Christian Men’s Association (YMCA) meeting on May 19, 1865.

After the war, Leonard Johnson began using most of his island for agriculture. He also started a limestone quarry in its center. Shortly before his death in 1894, he leased part of the island to the Pleasure Resort Company. In its first season most of its buildings consisted of wooden frames covered in canvas because of their cost effectiveness and speed at which they could be erected. Guests could attend the concerts by the People’s Orchestra on Sundays, watch the human pretzel Monsieur Victor and other Vaudeville-type acts, and attend dances under a pavilion. The concession stand was eventually replaced by a full-sized restaurant.

One of the more surprising artifacts on display at the museum was a zinc statue of the Shakespearean character Puck from A Midsummer’s Night Dream. Designed by sculptor Casper Buberl, it was a mass-produced item made by the William Demuth Company of New York and patented in 1881. The one in the Follett House stood in the window of the Dietz & Mischler Cigar Store from 1895 to 1918. In the 1920s it made its way to the Weir Brothers Scrap Yard from which it was found and mounted on top of Charlie Hoffman’s ice cream stand. For seventy-three years Ritter Cigar Factory and Store displayed its own sculpture, Punch, which had been carved from a spar broken off a ship docked in New York and brought back to Sandusky by the store’s owner, Henry Ritter. Although it stood outside, it was brought in each night, which probably explains its longevity.

Hanging on one of the museum’s walls is a decaying Confederate flag that once belonged to Brigadier General Felix K. Zollicoffer from Tennessee. Union surgeon Doctor Robert R. McMeens “captured” it in July 1861. According to a museum information sign, he took it from “an abandoned Confederate hospital tent near Huttonsville, West Virginia.” Just over a year later McMeens died of an unnamed disease near Perryville, Kentucky, but his prize made its way north.

The museum has some of its artifacts from the Civil War prison camp on nearby Johnson’s Island that includes a pair of cast iron stove doors, a barber chair made by a prisoner, and a civilian pass to get into the prison. Possibly the most precious item is a small book published in 1872 containing a poem written by one of the prison’s former inmates, Irl Hicks. Its title, The Prisoner’s Farewell to Johnson’s Island: Or, Valedictory Address to the Young Men’s Christian Association of Johnson’s Island, Ohio: A Poem, is also a synopsis of its content. Hicks recited it for the first time at the camp’s last Young Christian Men’s Association (YMCA) meeting on May 19, 1865.

After the war, Leonard Johnson began using most of his island for agriculture. He also started a limestone quarry in its center. Shortly before his death in 1894, he leased part of the island to the Pleasure Resort Company. In its first season most of its buildings consisted of wooden frames covered in canvas because of their cost effectiveness and speed at which they could be erected. Guests could attend the concerts by the People’s Orchestra on Sundays, watch the human pretzel Monsieur Victor and other Vaudeville-type acts, and attend dances under a pavilion. The concession stand was eventually replaced by a full-sized restaurant.

The resort did quite well but was undone by a terrible accident at six in the evening on Sunday, August 8, 1897. A company managed by Arthur Ledyard was in charge of releasing two hot air balloons. Ledyard borrowed a gun that he planned to fire to signal the balloons’ release. Suddenly one of them launched prematurely and it looked as if the trapeze artist accompanying it, Mille Sheets, was tangled in its rope. Panicked by the sight, Ledyard discharged the pistol into the crowd of 5,000. He had incorrectly assumed it contained blanks, but such was not the case. A bullet hit Fredrick C. Linden of Chicago Junction (now Willard) in the heart, killing him instantly beside his wife and daughter.

Ledyard was arrested and Linden’s widow sued the resort for $10,000. That December the main pavilion burned down, so the resort didn’t reopen the next year. In 1899 most of Johnson’s island was sold in a sheriff’s sale to two Sandusky men, Charles Dick and James H. Emrich. In 1904 two steamboat captains, C.L. Goodsite and Andrew Geisendorfer, reopened the resort complete with a new pavilion, a boathouse and bathhouse. New attractions included roller skating, small boats for rent, and baseball games. A midway was added as was a movie theater. For its first four years it did well, but competition with other resorts such as Cedar Point made its longtime success unlikely, so Emrich agreed to sell out to that aforementioned amusement park. And so ended the island’s resort era.

Dick, who had encouraged the establishment of the second resort, expanded the quarry’s operation. In 1956 his heirs sold the island to Johnson’s Island Incorporated of Cleveland, which divided it into lots. The island was connected to the mainland with a causeway that anyone can use so long as they pay the toll.

More about Johnson Island’s time as a POW camp for Confederate officers and a plot by Confederates to raid the island and free them can be found in Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Erie County.🕜

Ledyard was arrested and Linden’s widow sued the resort for $10,000. That December the main pavilion burned down, so the resort didn’t reopen the next year. In 1899 most of Johnson’s island was sold in a sheriff’s sale to two Sandusky men, Charles Dick and James H. Emrich. In 1904 two steamboat captains, C.L. Goodsite and Andrew Geisendorfer, reopened the resort complete with a new pavilion, a boathouse and bathhouse. New attractions included roller skating, small boats for rent, and baseball games. A midway was added as was a movie theater. For its first four years it did well, but competition with other resorts such as Cedar Point made its longtime success unlikely, so Emrich agreed to sell out to that aforementioned amusement park. And so ended the island’s resort era.

Dick, who had encouraged the establishment of the second resort, expanded the quarry’s operation. In 1956 his heirs sold the island to Johnson’s Island Incorporated of Cleveland, which divided it into lots. The island was connected to the mainland with a causeway that anyone can use so long as they pay the toll.

More about Johnson Island’s time as a POW camp for Confederate officers and a plot by Confederates to raid the island and free them can be found in Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Erie County.🕜

Bird's-Eye View of Sandusky.

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.