Harrison County History of Coal Museum

Inside the Museum

Strip Mining Operation

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

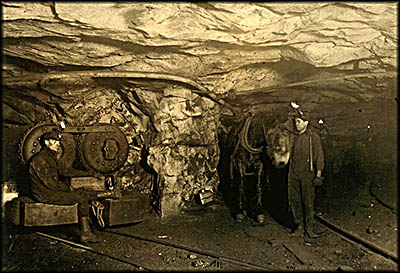

Coal Mine Mule and Handler

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Although the Harrison County History of Coal Museum’s display area isn’t especially large, it is filled with artifacts such as a mine car once used in the Ohio & Penna Coal Company as well as equipment used by miners. Hats with lamps mounted in front were sometimes family heirlooms passed down from father to son to grandson, even when more modern ones that offered better head protection existed. In the days before the electric lightbulb filled a hat’s lamp, open flames were used. To help prevent them from igniting explosive gas, they were enclosed in glass or behind a screen. Later the methane detector was used to prevent explosions. Canaries and other birds were replaced with carbon monoxide detectors. Mine inspectors used the anemometer to check the air flow.

There is much about mine workers and their lives, including one unsung member: the mule. Although one might think the electric locomotive would have replaced this hardy animal in the twentieth century, such was not the case. They were still being used as late as the 1950s. Many mines employed electric locomotives to move the cars in the main line and mules to pull them in the side tunnels. Mules were preferred over horses because they could be hitched single file rather than side by side, they were hardier, not as likely to spook, and ate and drank less.

Mining mules were specially bred for this purpose. Like humans, each had a distinct personality and its own quirks. Some mules could be controlled by patting them on the head while others needed severer methods of control, including use of the outlawed whip. Most were treated humanely because their handlers became attached to them. Some mules only worked well for a particular handler. Others refused to work until receiving a ration of chewing tobacco.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries mines were filled with immigrants who spoke a babel of languages, meaning mules often only responded to commands in a language other than English. One mule in Gary Hollow, West Virginia, was limited to Italian. When not working, mules were kept in underground stalls. Here rats had a habit of eating the mules’ food, and when efforts were made to prevent the rats from doing so, they got vicious and gnawed on the mules’ hooves. The mules didn’t take kindly to this, so finding a room full of dead rats tramped to death was not unknown.

In the darkest part of the mine the lead mule had a headlamp. Despite sometimes being kept underground for years at a time, when allowed into daylight, mules were surprisingly quick to regain their outdoor eyesight. What they didn’t like was eating the grass now available beneath their hooves. Most only worked for two to three years before being retired. When hurt too badly for recover, stablemasters put them down. Sometimes mules broke free from their chains and, while dragging them, accidently made contact with an electric rail, resulting in electrocution.

When I discovered the museum had a little theater, I asked a librarian if there was something to watch in it. There was. A few other visitors and I sat down to view Coal: The Inside Story. Although it is really just a public relations piece produced by American Electric Power (AEP) in 1989 with the purpose of putting coal and its production in a heavenly light, it’s nonetheless very informative. I learned all sorts of new coal mining jargon in general and about strip mining in particular. Overburden, for example, is all the earth removed to get at the coal.

Strip mining is only economical when the coal is close to the surface. Its history in Appalachia goes much further back than one might expect. The area’s earliest white settlers stripped the land using draft animals dragging scrappers, but the impact on the land and the ability to go deep were limited. It wasn’t until the introduction of power equipment such as the steam shovel that it would be done on an industrial scale. The first steam shovel used for strip mining was employed in 1877 near Pittsburg, Kansas. Within a few years these machines appeared in Pennsylvania’s anthracite fields, but strip mining was only viable on flat land.

Mining mules were specially bred for this purpose. Like humans, each had a distinct personality and its own quirks. Some mules could be controlled by patting them on the head while others needed severer methods of control, including use of the outlawed whip. Most were treated humanely because their handlers became attached to them. Some mules only worked well for a particular handler. Others refused to work until receiving a ration of chewing tobacco.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries mines were filled with immigrants who spoke a babel of languages, meaning mules often only responded to commands in a language other than English. One mule in Gary Hollow, West Virginia, was limited to Italian. When not working, mules were kept in underground stalls. Here rats had a habit of eating the mules’ food, and when efforts were made to prevent the rats from doing so, they got vicious and gnawed on the mules’ hooves. The mules didn’t take kindly to this, so finding a room full of dead rats tramped to death was not unknown.

In the darkest part of the mine the lead mule had a headlamp. Despite sometimes being kept underground for years at a time, when allowed into daylight, mules were surprisingly quick to regain their outdoor eyesight. What they didn’t like was eating the grass now available beneath their hooves. Most only worked for two to three years before being retired. When hurt too badly for recover, stablemasters put them down. Sometimes mules broke free from their chains and, while dragging them, accidently made contact with an electric rail, resulting in electrocution.

When I discovered the museum had a little theater, I asked a librarian if there was something to watch in it. There was. A few other visitors and I sat down to view Coal: The Inside Story. Although it is really just a public relations piece produced by American Electric Power (AEP) in 1989 with the purpose of putting coal and its production in a heavenly light, it’s nonetheless very informative. I learned all sorts of new coal mining jargon in general and about strip mining in particular. Overburden, for example, is all the earth removed to get at the coal.

Strip mining is only economical when the coal is close to the surface. Its history in Appalachia goes much further back than one might expect. The area’s earliest white settlers stripped the land using draft animals dragging scrappers, but the impact on the land and the ability to go deep were limited. It wasn’t until the introduction of power equipment such as the steam shovel that it would be done on an industrial scale. The first steam shovel used for strip mining was employed in 1877 near Pittsburg, Kansas. Within a few years these machines appeared in Pennsylvania’s anthracite fields, but strip mining was only viable on flat land.

Strip mining didn’t become common in Appalachia until improved roads to move the coal were built and enough demand existed to make it profitable. After World War I farmers in Harrison County began selling their land to mining companies intending to strip it, but it wasn’t until 1948 and intense post-World War II demand for coal that the county had its first successful strip mine. A characteristic of Ohio’s strip mines were their supersized earth removal machines. The largest of these was Big Muskie, which had a base length of 140 feet, a width of 120 feet, and a height of forty feet. These measurements didn’t include its 310-foot boom, which was longer than a football field. Its purpose was to remove the overburden. Normal dragline excavators were used to dig up the coal itself.

Big Muskie was also tasked with replacing soil to dig areas when coal beneath seam was exhausted. According Coal: The Inside Story, AEP was committed to restoring the land after stripping it. It is rare that a for-profit company will spend the kind of money takes to accomplish this unless something compelled it to, and probably AEP went to all this trouble because the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act made it to do so. Still, many strip mine companies at that time not only refused to replenish the stripped land, they wouldn’t even pay the penalties, so one must give AEP credit where it’s due.

Upon closing one of its strip mines that spanned across Muskingum, Noble, Morgan, and Guernsey Counties, AEP restored much of the lost topsoil and planted over 63 million trees. The effort also produced 350 ponds and lakes. In 1971 it opened this area for public use, and in 2017 the State of Ohio started an effort to acquire it. In 1998, AEP donated 9,000 acres of restored Muskingum County land to the International Center for the Preservation of Wild Animals whose membership includes Columbus Zoological Gardens and the Pittsburgh and Cincinnati Zoos. It still exists and is called the Wilds. It is not to be confused with the former private one at Zanesville where its owner released the animals, then shot himself. This forced police to put down many of the animals including Bengal tigers.

Big Muskie was also tasked with replacing soil to dig areas when coal beneath seam was exhausted. According Coal: The Inside Story, AEP was committed to restoring the land after stripping it. It is rare that a for-profit company will spend the kind of money takes to accomplish this unless something compelled it to, and probably AEP went to all this trouble because the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act made it to do so. Still, many strip mine companies at that time not only refused to replenish the stripped land, they wouldn’t even pay the penalties, so one must give AEP credit where it’s due.

Upon closing one of its strip mines that spanned across Muskingum, Noble, Morgan, and Guernsey Counties, AEP restored much of the lost topsoil and planted over 63 million trees. The effort also produced 350 ponds and lakes. In 1971 it opened this area for public use, and in 2017 the State of Ohio started an effort to acquire it. In 1998, AEP donated 9,000 acres of restored Muskingum County land to the International Center for the Preservation of Wild Animals whose membership includes Columbus Zoological Gardens and the Pittsburgh and Cincinnati Zoos. It still exists and is called the Wilds. It is not to be confused with the former private one at Zanesville where its owner released the animals, then shot himself. This forced police to put down many of the animals including Bengal tigers.

Ohio’s coal mining industry severely declined mostly because of the Clean Air Act of 1970, a stronger version of the 1963 law that led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and gave it the ability to set limits on some pollutants. The latter Clean Air Act made Ohio’s coal reserves undesirable because its content of about 3.5 percent sulfur made it too dirty to burn without costly scrubbers. To make Ohio’s coal more attractive, the Ohio Coal Research and Development Office in partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy developed the concept of so-called clean coal, an oxymoron if ever there were one.

Unfortunately the museum was bamboozled by this imaginary type of coal and put up an information sign about its benefits. Pushers of this fantasy claim it can be done with a combination of scrubbers to remove sulfur, washing the coal itself to remove soil on it, then capturing and storing the carbon dioxide that is produced, which is called carbon capture and store. What would one do with all that the CO2? Since it can’t be released into the atmosphere, the idea is to push it deep underground where it will chemically bind itself to rocks.

Even if all those ideas were implemented and it actually worked, the processes still wouldn’t prevent the myriad of unhealthy substances bound to coal—mercury chief among them—from getting into the atmosphere. Mercury, which rarely gets into the ecosystem on its own, is especially dangerous for children. It can cause learning disabilities and birth defects in unborn babies. More than fifty percent of all mercury in our ecosystem comes from the burning of coal. Even if all the mercury were removed, burned coal creates particles so small few air filters can capture them that, when it gets into human lungs, does all sorts of unpleasant things such as exasperate asthma and cause heart attacks.

Coal was used in prehistoric times, probably for cooking fuel, and was mined as early as 3,000 years ago by the Chinese. The English mined it from 1233 to 1306 when King Edward I banned its use because its smoke smelled terrible and he figured it was probably bad for public health. By 1700 the English were using it again in part to fuel the Industrial Revolution. It served as an alternative to the wood that had become scarce after the British cut down most of their trees.

More about the history of coal mining in Ohio can be found in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Harrison County.🕜

Unfortunately the museum was bamboozled by this imaginary type of coal and put up an information sign about its benefits. Pushers of this fantasy claim it can be done with a combination of scrubbers to remove sulfur, washing the coal itself to remove soil on it, then capturing and storing the carbon dioxide that is produced, which is called carbon capture and store. What would one do with all that the CO2? Since it can’t be released into the atmosphere, the idea is to push it deep underground where it will chemically bind itself to rocks.

Even if all those ideas were implemented and it actually worked, the processes still wouldn’t prevent the myriad of unhealthy substances bound to coal—mercury chief among them—from getting into the atmosphere. Mercury, which rarely gets into the ecosystem on its own, is especially dangerous for children. It can cause learning disabilities and birth defects in unborn babies. More than fifty percent of all mercury in our ecosystem comes from the burning of coal. Even if all the mercury were removed, burned coal creates particles so small few air filters can capture them that, when it gets into human lungs, does all sorts of unpleasant things such as exasperate asthma and cause heart attacks.

Coal was used in prehistoric times, probably for cooking fuel, and was mined as early as 3,000 years ago by the Chinese. The English mined it from 1233 to 1306 when King Edward I banned its use because its smoke smelled terrible and he figured it was probably bad for public health. By 1700 the English were using it again in part to fuel the Industrial Revolution. It served as an alternative to the wood that had become scarce after the British cut down most of their trees.

More about the history of coal mining in Ohio can be found in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Harrison County.🕜

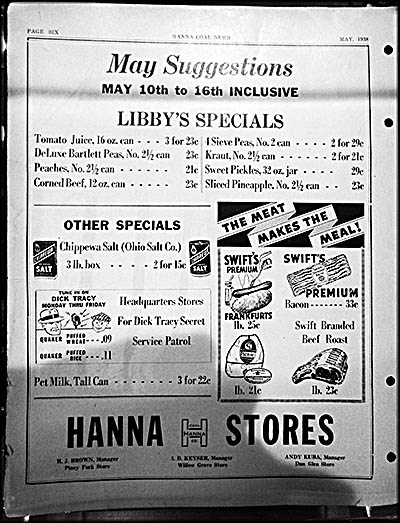

An ad for the Hanna Company Stores, the only place miners could buy goods with their pay, which came in the form of scrip.

One of the ingredients of Denorex is coal.

Wellstone Company Store

Library of Congress

Library of Congress