Zoar Village

Heritage Village Museum

Gatch Barn

Replica of a flatboat of the sort used on the Ohio River.

Hayner House

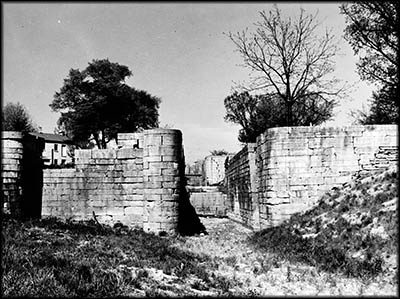

Ruins of the Miami & Erie Canal lock Lockington, Ohio.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Somerset Presbyterian Church

Myers School

Doctor Henry Langdon's Office

Chester Park Train Station

McAplin's Clock

Fetter General Store

Vorhes House

Elk Lick House

Hand-Pumped Vacuum Cleaner

(Plus A Ghost Hunting Expedition)

If there’s one thing I love, it’s a living museum—a place consisting of authentic historic buildings stocked with historical reenactors who show visitors what life was like during the era the museum represents. The Heritage Village Museum and Education Center, which is located in Sharonville, Ohio’s Sharon Woods, it’s an excellent example of this type. To visit the museum you first have to pay to park in Sharon Woods unless you possess a parking permit good for all the parks controlled by the Great Parks of Hamilton County system. You then pay an additional fee to visit Heritage Village. While a self-guided tour costs less, I recommend the guided one because it gives you access to the interior of some of the village’s buildings you otherwise can’t get in. Another drawback of the self-guided tour is that information signs are a rarity, although there are historical reenactors who will tell you about the place in which they reside.

On the day my traveling companions and I visited, there was a special event running from seven to nine that evening called the Spirts by Starlight Ghost Tour. It sounded interesting, so my traveling companions and I paid extra for this as well. I like ghost tours of historic places because you often learn the more lurid aspects of their history. It turned out not to be quite what I’d imaged, but I’ll get to that later.

Heritage Village began in 1968 and first opened in 1971. Its mission is to rescue historic buildings in the Ohio Valley, relocate and restore them at the museum’s site. You pay to get in at the gift shop in the Hayner House, which John Hayner had built near South Lebanon in the 1850s. It stood along the banks of the Little Miami River and was the centerpiece of his corn and canning operation. This is the only structure with stairs you can climb without first getting acrobatic training, although the upper floors aren’t open to the public. Hayner also served as president of the Lebanon National Bank, not a usual side vocation for a successful businessman of that era.

On the day my traveling companions and I visited, there was a special event running from seven to nine that evening called the Spirts by Starlight Ghost Tour. It sounded interesting, so my traveling companions and I paid extra for this as well. I like ghost tours of historic places because you often learn the more lurid aspects of their history. It turned out not to be quite what I’d imaged, but I’ll get to that later.

Heritage Village began in 1968 and first opened in 1971. Its mission is to rescue historic buildings in the Ohio Valley, relocate and restore them at the museum’s site. You pay to get in at the gift shop in the Hayner House, which John Hayner had built near South Lebanon in the 1850s. It stood along the banks of the Little Miami River and was the centerpiece of his corn and canning operation. This is the only structure with stairs you can climb without first getting acrobatic training, although the upper floors aren’t open to the public. Hayner also served as president of the Lebanon National Bank, not a usual side vocation for a successful businessman of that era.

Along the wall of one of the rooms, which is actually two rooms with a wall removed, there is an exhibit about the Miami & Erie Canal. Connecting Toledo and Cincinnati, at its peak it spanned 274 miles. Construction on it began in 1825, but by the time of its completion in 1845, railroads had made it effectively obsolete. At its peak, Ohio’s canal system stretched to about 1,000 miles. Despite its obsolesce, parts of it were in use until the Great Flood of 1913. Ohio’s canals were standardized to be a minimum of forty feet wide at their crest, twenty-six feet wide at their bottom, and four feet deep. Most adults have to try really hard to drown in one. Canal locks that could hold up to 120,000 gallons of water were built to accommodate elevation changes.

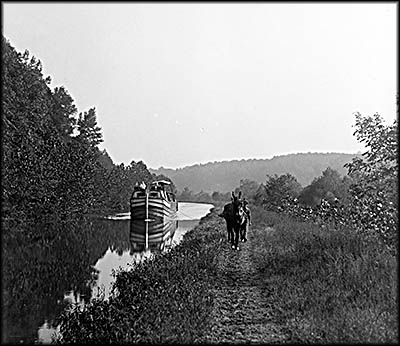

Canal boats weren’t speed demons. The average speed was 1½ mph with the allowed maximum being four. While variations occurred, canal boats were pretty uniform. They had flat bottoms and carried between fifty and eighty tons of cargo plus passengers (if any) and crew. Crews usually consisted of the captain, cook, and two steersmen—one in front and one in the rear. Until the introduction of steam engines designed specifically for canal boats, a team of mules on a towpath pulled them. Canal boats usually had three cabins: one for the captain, one for the crew, and one for mules and their food. The captain’s cabin in the rear also had a cooking stove.

An information sign says passengers paid four cents per mile, but I’m sure that price changed over time due to inflation. Passengers were fed, received a berth, and even entertained. A boat going four miles an hour traveling twenty-four hours a day would theoretically be able to go from one end of the canal to the other in a bit over three days, but in reality the trips were much longer. There were the inevitable backups at locks, changes in mule teams, and other unexpected obstacles.

Canal boats weren’t speed demons. The average speed was 1½ mph with the allowed maximum being four. While variations occurred, canal boats were pretty uniform. They had flat bottoms and carried between fifty and eighty tons of cargo plus passengers (if any) and crew. Crews usually consisted of the captain, cook, and two steersmen—one in front and one in the rear. Until the introduction of steam engines designed specifically for canal boats, a team of mules on a towpath pulled them. Canal boats usually had three cabins: one for the captain, one for the crew, and one for mules and their food. The captain’s cabin in the rear also had a cooking stove.

An information sign says passengers paid four cents per mile, but I’m sure that price changed over time due to inflation. Passengers were fed, received a berth, and even entertained. A boat going four miles an hour traveling twenty-four hours a day would theoretically be able to go from one end of the canal to the other in a bit over three days, but in reality the trips were much longer. There were the inevitable backups at locks, changes in mule teams, and other unexpected obstacles.

Aside from passengers, canal boats carried freight. In 1851 a uniform system to charge for this cargo was implemented by weighing the boat in the lock. The boat’s known weight was subtracted from its total to determine this number. The price was also adjusted for the type of cargo. The information sign didn’t mention this, but I learned during previous research into Ohio’s canals that many captains hid the goods that cost more to transport to avoid higher costs. Some cargo boats only plied between toll stations but never stopped at them, thus sailing for free, or at least minus the toll charge. The animals that pulled the boats, their feed, and their handlers still had to be paid for.

The museum’s guided tour began at the Kemper Log House, the village’s first rescued building. I failed to take a photo of it because at the time our guide was moving too fast, and I didn’t think to get one later. A detached stone kitchen stands beside it. This is only one of the only three replicas in the village. (The others are a flatboat and McAlpin’s Clock, which was built in 1992.) In the days when cooking was done primarily using a fireplace, homes often had a separate kitchen so if it caught fire, it wouldn’t take the main house down. Some houses did have kitchens within plus a detached summer kitchen so as not to heat up the main house.

Our guide made it a point to say this was a log house and not a cabin, the difference being it was meant to be permanent and it had wooden, not dirt, floors. In its original form, a person might not realize it was made of logs because it was covered with shingles meant to protect the chinking filling the space between the logs from being exposed to the elements and thus falling out. The house was constructed by Reverend James Kemper, the first ordained Presbyterian minister in Ohio. Being a circuit rider—that is, he rode on a predetermined route to the various congregations along it—he was frequently away. This didn’t stop him from fathering fifteen children, the last of which was born on the day he and his family moved in.

The museum’s guided tour began at the Kemper Log House, the village’s first rescued building. I failed to take a photo of it because at the time our guide was moving too fast, and I didn’t think to get one later. A detached stone kitchen stands beside it. This is only one of the only three replicas in the village. (The others are a flatboat and McAlpin’s Clock, which was built in 1992.) In the days when cooking was done primarily using a fireplace, homes often had a separate kitchen so if it caught fire, it wouldn’t take the main house down. Some houses did have kitchens within plus a detached summer kitchen so as not to heat up the main house.

Our guide made it a point to say this was a log house and not a cabin, the difference being it was meant to be permanent and it had wooden, not dirt, floors. In its original form, a person might not realize it was made of logs because it was covered with shingles meant to protect the chinking filling the space between the logs from being exposed to the elements and thus falling out. The house was constructed by Reverend James Kemper, the first ordained Presbyterian minister in Ohio. Being a circuit rider—that is, he rode on a predetermined route to the various congregations along it—he was frequently away. This didn’t stop him from fathering fifteen children, the last of which was born on the day he and his family moved in.

The house originally stood in Cincinnati’s Walnut Hills neighborhood and overlooked the Ohio River. Kemper and his descendants occupied it from 1804 until 1897. It sat unused until 1912 when it was moved to the Cincinnati Zoo. This zoo didn’t take very good care of it, and in the 1950s repurposed it to be the sort of house Davy Crocket might’ve lived in. This was done because the success of Disney’s Davy Crocket miniseries in 1954 and 1955 had made this historic person a cultural icon for American children of this era. The house was therefore changed to attract them to the zoo. Heritage Village painstakingly restored it before its debut in 1971.

Next to the Kemper House is the Somerset Presbyterian Church, which was originally built around 1829. Its congregation had broken away from the Montgomery Presbyterian Church, one established by Kemper in 1801. Despite this apparent schism, Kemper installed Somerset’s first minister, Ludwell Gaines, on May 7, 1822. Never have I seen a more austere interior. Little decorates this simple yet acoustically brilliant building. It’s typical of the Presbyterian Churches of that era, Presbyterianism being a Calvinist-inspired religion that hated any sort of iconography associated with the Roman Catholic Church.

On the other side of the church is Myers Schoolhouse, a one-room affair that once served Delhi Township. Opening in 1891, its name was to honor township trustee Cornelius Myers. Being the village’s most recent acquisition, it’s still undergoing renovations, so we didn’t enter. Which is fine for me because been in countless one-room schoolhouses and can safely say when you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all. This particular one is, I must admit, the largest example I’ve seen, and it has a bell tower, something not all of them possessed. It also has a roof made of wooden tiles, making a small miracle that it never caught on fire and burned down. The school was used until 1926 when all of Delhi Township schools were consolidated.

Next, we visited the Dr. Henry Langdon’s office. The Heritage Village’s brochure calls its architectural design “Steamboat Gothic,” which is when a house is made to look like a river steamboat. It was a style popular in the nineteenth century in Ohio and Mississippi Valleys. Webster’s Dictionary says the term was coined in 1941, but the Oxford English Dictionary has its first use in 1962. I don’t think the house looks anything like a nineteenth century riverboat. It more closely resembles the style of Franklin Lloyd Wright despite predating his years as an active architect.

Next to the Kemper House is the Somerset Presbyterian Church, which was originally built around 1829. Its congregation had broken away from the Montgomery Presbyterian Church, one established by Kemper in 1801. Despite this apparent schism, Kemper installed Somerset’s first minister, Ludwell Gaines, on May 7, 1822. Never have I seen a more austere interior. Little decorates this simple yet acoustically brilliant building. It’s typical of the Presbyterian Churches of that era, Presbyterianism being a Calvinist-inspired religion that hated any sort of iconography associated with the Roman Catholic Church.

On the other side of the church is Myers Schoolhouse, a one-room affair that once served Delhi Township. Opening in 1891, its name was to honor township trustee Cornelius Myers. Being the village’s most recent acquisition, it’s still undergoing renovations, so we didn’t enter. Which is fine for me because been in countless one-room schoolhouses and can safely say when you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all. This particular one is, I must admit, the largest example I’ve seen, and it has a bell tower, something not all of them possessed. It also has a roof made of wooden tiles, making a small miracle that it never caught on fire and burned down. The school was used until 1926 when all of Delhi Township schools were consolidated.

Next, we visited the Dr. Henry Langdon’s office. The Heritage Village’s brochure calls its architectural design “Steamboat Gothic,” which is when a house is made to look like a river steamboat. It was a style popular in the nineteenth century in Ohio and Mississippi Valleys. Webster’s Dictionary says the term was coined in 1941, but the Oxford English Dictionary has its first use in 1962. I don’t think the house looks anything like a nineteenth century riverboat. It more closely resembles the style of Franklin Lloyd Wright despite predating his years as an active architect.

No matter who designed his office or what style it’s in, Doctor Langdon was a trained surgeon who’d served in the Union Army during the Civil War. Upon its conclusion, he started his practice on Cincinnati’s Eastwood Avenue. He became a physician during the time when the “theory” of the four humors—bodily fluids that consisted of blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm—was giving way to germ theory. The idea of humors was invented by ancient Greek philosophers. It was believed illness was caused when the humors were out of alignment. The cure was to restore this balance, and one of the best ways to do so was blood letting, which was most commonly done either by cutting open a vein or using leeches.

Dr. Langdon embraced both the humor and germ theories (although I hesitate consider this humor business a theory because that give’s a sheen of scientific respectability). Whether he would’ve completely abandoned the idea of humors along with most of his contemporaries is unknown nearer the end of the nineteenth century is unknown. He died at the age of thirty-seven.

Buildings into which we didn’t go included Benedict Cottage, the Fetter General Store and Schram Print Shop, and the Chester Park Train Station. This last was once a stop on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (now part of the CSX) that stood on Cincinnati’s Spring Groove Avenue. Built in 1875, it was constructed to accommodate crowds going to the Chester Park Racetrack, which later became an amusement park that closed sometime between 1932 and 1935.

After our tour, we ate at a local restaurant, the Blue Goose (in which you can view a truly awful mural that has to be seen to be believed), then we retired to our hotel. We returned to the park about twenty minutes before the Spirts by Starlight Ghost Tour started only to find Heritage Village’s gates closed, leaving us with no idea how to get in. We did see cars parked inside the village, so clearly there was a way. Fortunately one of the tour guides went looking for us and told us to take a service road to get inside. It turns out I’d received an email earlier that day explaining all this, but I hadn’t looked at it that day.

Dr. Langdon embraced both the humor and germ theories (although I hesitate consider this humor business a theory because that give’s a sheen of scientific respectability). Whether he would’ve completely abandoned the idea of humors along with most of his contemporaries is unknown nearer the end of the nineteenth century is unknown. He died at the age of thirty-seven.

Buildings into which we didn’t go included Benedict Cottage, the Fetter General Store and Schram Print Shop, and the Chester Park Train Station. This last was once a stop on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (now part of the CSX) that stood on Cincinnati’s Spring Groove Avenue. Built in 1875, it was constructed to accommodate crowds going to the Chester Park Racetrack, which later became an amusement park that closed sometime between 1932 and 1935.

After our tour, we ate at a local restaurant, the Blue Goose (in which you can view a truly awful mural that has to be seen to be believed), then we retired to our hotel. We returned to the park about twenty minutes before the Spirts by Starlight Ghost Tour started only to find Heritage Village’s gates closed, leaving us with no idea how to get in. We did see cars parked inside the village, so clearly there was a way. Fortunately one of the tour guides went looking for us and told us to take a service road to get inside. It turns out I’d received an email earlier that day explaining all this, but I hadn’t looked at it that day.

We assembled in the Hayner House in the same room that had the canal exhibit. It turned out we’d be hunting for ghosts rather than walking around and listening to ghost stories. One of our guides, Violet Shindler, insisted that we weren’t “hunting” ghosts but rather seeking them out. She also said that when the buildings were relocated to village, the ghosts tied to them came along.

Our guides produced a variety of equipment to find said ghosts. I was given a motion detector that failed to detect anything and which I accidentally left behind, though it was later recovered. My brother was handed a device labeled “The Ghost Meter” that measures magnetic field strength. Violet had on her phone a ghost box app that monitored a variety of radio channels and other signals because, she claimed, ghosts sometimes use these to communicate. If any of us thought we heard a legitimate message, we were welcome to speak to it. I asked the ghost box for the next day’s winning lottery numbers and was met with silence.

I had little desire to seek out ghosts and never during the night did I or my travel companions see one. Nor could my brother find one with the ghost meter. But there was a silver lining to this venture, which is why I included some of the details about it here. We were given free reign to look where we wanted and go into any room in the buildings we entered. Such unfettered access is catnip for me. The downside is that save for the last place we visited, we needed flashlights to see, lessening opportunities for the taking of decent photos.

One of the places we went in was the Samuel and Jane Vorhes House. Likely built between 1820 and 1840, it stood on Cornell Road in Blue Ash and was the family’s house on its 123 acre farm. Samuel and Jane had thirteen children, a frequent occurrence in this era not only for lack of birth control, but also because children were made into unpaid farmhands who were effectively indentured servants with no rights until they came of age.

During the day the house is used to demonstrate spinning wheels and looms. Nineteenth century farm families such as the Vorhes needed these tools and skills because they made all their clothes from scratch. The house had two rooms on the ground floor and two on the upper, leaving little room for its many inhabitants. The family therefore used the side porch as an extra space for washing, storage, entertaining visitors, or whatever else was needed.

During the guided tour we were informed that the fire marshal forbade the public from climbing the steep steps in both rooms because they are tight and winding. During the ghost tour we were allowed to ascend these and see the treasures upstairs. Here the museum stores its vast collection of nineteenth century artifacts on shelves including a collection of lanterns once used by railroad workers.

Our guides produced a variety of equipment to find said ghosts. I was given a motion detector that failed to detect anything and which I accidentally left behind, though it was later recovered. My brother was handed a device labeled “The Ghost Meter” that measures magnetic field strength. Violet had on her phone a ghost box app that monitored a variety of radio channels and other signals because, she claimed, ghosts sometimes use these to communicate. If any of us thought we heard a legitimate message, we were welcome to speak to it. I asked the ghost box for the next day’s winning lottery numbers and was met with silence.

I had little desire to seek out ghosts and never during the night did I or my travel companions see one. Nor could my brother find one with the ghost meter. But there was a silver lining to this venture, which is why I included some of the details about it here. We were given free reign to look where we wanted and go into any room in the buildings we entered. Such unfettered access is catnip for me. The downside is that save for the last place we visited, we needed flashlights to see, lessening opportunities for the taking of decent photos.

One of the places we went in was the Samuel and Jane Vorhes House. Likely built between 1820 and 1840, it stood on Cornell Road in Blue Ash and was the family’s house on its 123 acre farm. Samuel and Jane had thirteen children, a frequent occurrence in this era not only for lack of birth control, but also because children were made into unpaid farmhands who were effectively indentured servants with no rights until they came of age.

During the day the house is used to demonstrate spinning wheels and looms. Nineteenth century farm families such as the Vorhes needed these tools and skills because they made all their clothes from scratch. The house had two rooms on the ground floor and two on the upper, leaving little room for its many inhabitants. The family therefore used the side porch as an extra space for washing, storage, entertaining visitors, or whatever else was needed.

During the guided tour we were informed that the fire marshal forbade the public from climbing the steep steps in both rooms because they are tight and winding. During the ghost tour we were allowed to ascend these and see the treasures upstairs. Here the museum stores its vast collection of nineteenth century artifacts on shelves including a collection of lanterns once used by railroad workers.

The staff of Heritage Village considers the Elk Lick House the gem of their museum. The house is a sort of TARDIS in that it appears much smaller outside than within. This building once stood on the Little Miami River in Clermont County’s Elk Lick Valley. It was rescued before the valley was flooded by a dam built Army Corps of Engineers that created the East Fork Lake in 1978. Built in 1818, it began as a two-room cottage that over the years was built onto to create to the current house.

Thomas Morris bought the house in 1835. He became a staunch abolitionist after his mother refused to accept an inheritance of four slaves, although she notably didn’t free them, either. After being thrown into debtor’s prison because of a business failure, he became a lawyer and, later, law maker, using the latter position while serving in Ohio’s house of representatives and senate to work towards abolishing debtor’s prisons. (Congress outlawed them federally in 1833.) He also called for the direct election of U.S. senators and pushed through reforms in Ohio’s jury system.

Morris was staunch Democrat until being ejected from the party in January 1840 for his opposition to slavery. Undaunted, he joined the Liberty party and ran as the vice-president on its 1844 ticket with James G. Birney as the presidential candidate. The two won 2.3 percent of the national vote. On December 7 of that same year, Morris suffered an “apoplexy”—probably a heart attack—as entered the house through its front door. Before dying he uttered, “Oh Lord, have mercy on me!” His wife, Rachel, and his son-in-law continued to live in the house but ultimately lost it to foreclosure in 1852. Another widow, Mary Smith, bought it and she, too, lost it foreclosure in 1876. The house is decorated in the way she’d likely have had it in the 1870s. It was moved to Heritage Village in 1971.🕜

Thomas Morris bought the house in 1835. He became a staunch abolitionist after his mother refused to accept an inheritance of four slaves, although she notably didn’t free them, either. After being thrown into debtor’s prison because of a business failure, he became a lawyer and, later, law maker, using the latter position while serving in Ohio’s house of representatives and senate to work towards abolishing debtor’s prisons. (Congress outlawed them federally in 1833.) He also called for the direct election of U.S. senators and pushed through reforms in Ohio’s jury system.

Morris was staunch Democrat until being ejected from the party in January 1840 for his opposition to slavery. Undaunted, he joined the Liberty party and ran as the vice-president on its 1844 ticket with James G. Birney as the presidential candidate. The two won 2.3 percent of the national vote. On December 7 of that same year, Morris suffered an “apoplexy”—probably a heart attack—as entered the house through its front door. Before dying he uttered, “Oh Lord, have mercy on me!” His wife, Rachel, and his son-in-law continued to live in the house but ultimately lost it to foreclosure in 1852. Another widow, Mary Smith, bought it and she, too, lost it foreclosure in 1876. The house is decorated in the way she’d likely have had it in the 1870s. It was moved to Heritage Village in 1971.🕜

Boat on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress