INVENTION OF THE DRY CELL ALKALINE BATTERY

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

Luigi Galvani

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

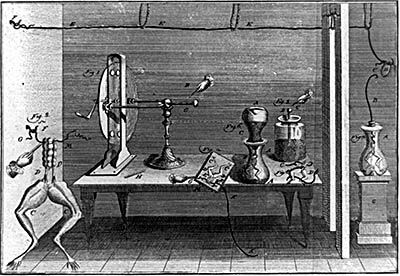

Frog legs made to twitch when jolted with electricity.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

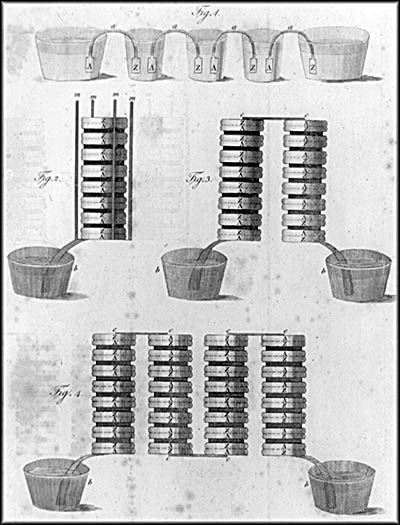

Diagram of Volta's Battery from 1800.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

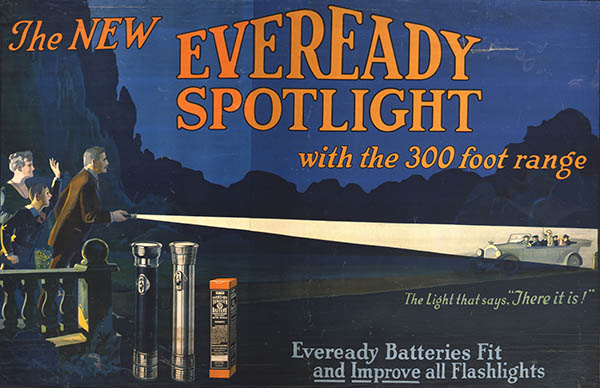

Eveready Ad

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The alkaline battery can trace is origin back to a twitching frog leg seen in 1786 in Bologna, Italy. This occurred when Luigi Galvani, a professor of anatomy, connected a brass wire to a frog’s leg and touched it with a steel scalpel. Astounded at this reaction, he knew he’d discovered something important, and theorized it was caused by some sort of electrical fluid within the frog’s leg (it wasn’t). He published this idea in his 1791 paper De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentaries (Commentary on the Effect of Electricity on Muscular Motion).

One scholar who read it was Alessandro Volta, the professor of experimental physics at the University of Pavia. Intrigued, he decided to examine this phenomenon further. He doubted the twitching had been caused by any sort of fluid, instead hypothesizing that the leg served as a conductor between the two different metals. To test this idea, he constructed what became know as a “voltaic pile,” a device consisting of a piece of brine-soaked cardboard sandwiched between copper and zinc discs stacked on top of one another. When he connected the copper at the top with the zinc at the bottom via a conductor, he found it produced electricity, although he wasn’t sure why. What he’d done was produce a chemical reaction and thus the prototype that led to the modern battery. The cardboard served as its electrolyte, the catalyst which caused the chemical reaction that makes power.

One scholar who read it was Alessandro Volta, the professor of experimental physics at the University of Pavia. Intrigued, he decided to examine this phenomenon further. He doubted the twitching had been caused by any sort of fluid, instead hypothesizing that the leg served as a conductor between the two different metals. To test this idea, he constructed what became know as a “voltaic pile,” a device consisting of a piece of brine-soaked cardboard sandwiched between copper and zinc discs stacked on top of one another. When he connected the copper at the top with the zinc at the bottom via a conductor, he found it produced electricity, although he wasn’t sure why. What he’d done was produce a chemical reaction and thus the prototype that led to the modern battery. The cardboard served as its electrolyte, the catalyst which caused the chemical reaction that makes power.

Volta’s battery was useful for scientists in a laboratory, but it wasn’t good for anything outside that setting. The first low cost battery sold to the mass market didn’t appeared until 1866 when Frenchman George Leclanché introduced one with ammonia chloride (sal ammoniac) as its electrolyte. Put into a glass jar, millions were made to power things like doorbells, telegraphs and telephones. Better still, when one of these went dead, you just poured out the used sal ammoniac and put new in. On the downside, it ran down quickly, although most of the charge returned after it rested for a bit.

Useful as it was, Leclanché’s battery wasn’t practical for a lot of applications. You wouldn’t, for example, want to power a flashlight with it. German chemist Carl Gassner addressed this by patenting the world’s first dry cell battery in 1888, so called because it contains no liquid. This battery’s electrolyte consisted of plaster of Paris, a bit of zinc chloride, and ammonium chloride sealed in a zinc container. It could be tipped any which way without leaking. Thus was born the zinc-carbon battery.

One American company that began making dry cell batteries and battery powered consumer goods such as flashlights was the American Ever Ready Company. In 1913 it was acquired by the National Carbon Company, a subsidiary of the Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation, later just Union Carbide. Before National Carbon bought Eveready, it marketed its dry cell batteries under the name Columbia. After the purchase of Every Ready, Union Carbon rebranded its batteries as Eveready. The battery part of the company later became part of Union Carbide Battery Products Division.

Useful as it was, Leclanché’s battery wasn’t practical for a lot of applications. You wouldn’t, for example, want to power a flashlight with it. German chemist Carl Gassner addressed this by patenting the world’s first dry cell battery in 1888, so called because it contains no liquid. This battery’s electrolyte consisted of plaster of Paris, a bit of zinc chloride, and ammonium chloride sealed in a zinc container. It could be tipped any which way without leaking. Thus was born the zinc-carbon battery.

One American company that began making dry cell batteries and battery powered consumer goods such as flashlights was the American Ever Ready Company. In 1913 it was acquired by the National Carbon Company, a subsidiary of the Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation, later just Union Carbide. Before National Carbon bought Eveready, it marketed its dry cell batteries under the name Columbia. After the purchase of Every Ready, Union Carbon rebranded its batteries as Eveready. The battery part of the company later became part of Union Carbide Battery Products Division.

In the 1950s, a whole lot of products needed dry cell batteries such as flashlights, transistor radios, hearing aids, and a number of toys including robots, cars and walkie-talkies. There was only one problem. Existing zinc-carbon dry cell batteries, the descendants of Gassner’s design, didn’t last very long, a fact that hurt Eveready’s sales. It needed to find a way to extend the life of its batteries, so the decision was made to put someone in charge of figuring out how to do this. The company recruited one of its Canadian employees in Toronto, Lewis Frederick Urry, to head the project. He was an engineer working for Union Carbide’s subsidiary Canadian National Carbon. In 1955, the 28-year-old Urry transferred to National Carbon’s research facility in Parma, Ohio, to start the new project.

Born on January 29, 1927, in Pontypool, Canada, Urry’s father ran a garage in Beaverton that was the first to sell a Model T in that region. The garage sparked Urry’s interest in all things mechanical. He served in the Royal Canadian Army from 1946 to 1949, later achieving the rank of captain in its Reserve. In 1950, he earned a Bachelors of Science degree in chemical engineering at the University of Toronto. A few months later he went to work for Canadian National Carbon. After his transfer to Parma, he met and married Beverly Ann Carlock, prompting him to become a U.S. citizen.

Born on January 29, 1927, in Pontypool, Canada, Urry’s father ran a garage in Beaverton that was the first to sell a Model T in that region. The garage sparked Urry’s interest in all things mechanical. He served in the Royal Canadian Army from 1946 to 1949, later achieving the rank of captain in its Reserve. In 1950, he earned a Bachelors of Science degree in chemical engineering at the University of Toronto. A few months later he went to work for Canadian National Carbon. After his transfer to Parma, he met and married Beverly Ann Carlock, prompting him to become a U.S. citizen.

Finding that the life of a zinc-carbon battery couldn’t be extended, Urry decided to create something entirely new. He turned to using an alkaline as part of the electrolyte and found mixing it with manganese dioxide and solid zinc worked best. The trouble was he couldn’t get a sufficient amount of power. This he solved by using powdered zinc. Better still, the new battery could hold most of its charge even after a year in storage. Although it was Urry’s idea, his is not the only name on the patent issued on October 9, 1957. Karl Kordesch and Paul A. Marsal received equal credit.

Although he improved upon it, Urry didn’t invent the concept of the alkaline battery. Swiss engineer Ernst Waldemar Jungner had produced a nickel-iron alkaline battery in 1899. In 1901 Thomas Edison—or more likely someone in his employ—came up with his own version that was supposed to be sold to carmakers because at that time electric-powered vehicles still competed with ones using other power plants. The trouble was the battery didn’t work well and by the time it was perfected, nearly all auto manufacturers had switched to the internal-combustion engine.

Having accomplished his task, Urry needed to prove the alkaline battery’s viability. He went to a toy store, bought two battery-powered cars, and brought them to the research department’s cafeteria. In front of a few bosses, he put a traditional D-sized zinc-carbon battery in one car and his new alkaline version in the other. The zinc-carbon-powered car barely made it to the other side of the cafeteria. The alkaline-powered one kept going for so long that onlookers got bored and left.

Although he improved upon it, Urry didn’t invent the concept of the alkaline battery. Swiss engineer Ernst Waldemar Jungner had produced a nickel-iron alkaline battery in 1899. In 1901 Thomas Edison—or more likely someone in his employ—came up with his own version that was supposed to be sold to carmakers because at that time electric-powered vehicles still competed with ones using other power plants. The trouble was the battery didn’t work well and by the time it was perfected, nearly all auto manufacturers had switched to the internal-combustion engine.

Having accomplished his task, Urry needed to prove the alkaline battery’s viability. He went to a toy store, bought two battery-powered cars, and brought them to the research department’s cafeteria. In front of a few bosses, he put a traditional D-sized zinc-carbon battery in one car and his new alkaline version in the other. The zinc-carbon-powered car barely made it to the other side of the cafeteria. The alkaline-powered one kept going for so long that onlookers got bored and left.

So what did Union Carbide do with this new wonder battery? Not much. In 1959 it did begin production of a new battery labeled “Eveready Alkaline Energizer—the Long Life Power Cell,” which was made at Eveready’s Asheboro, North Carolina, factory. There it had a habit of smoking and sometimes exploding, so over the next six months Bob Scarr, Hal Hirt, Walk Rauske, and Jerry Winger solved the issue. Despite this early adoption, Eveready focused most of its energy on marketing its traditional zinc-carbon batteries, allowing Duracell to become the best-selling alkaline battery by the 1970s.

In 1980, Eveready introduced the Energizer alkaline battery. In the era of the Walkman and other portable devices, there was plenty of room for two big producers of alkaline batteries, allowing Energizer to catch up with Duracell in terms of sales. In the 1980s, an epidemic of hostile takeovers by corporate raiders erupted on Wall Street. To inoculate itself against this possibility, Union Carbide sold its profitable battery division to the Ralston Purina Company, the pet food maker. This benefited Union Carbine by making it less profitable and thus not worth a corporate raider’s effort.

Purina paid a massive $1.4 billion for it, creating so much debt that it, too, became unattractive for a hostile takeover. Purina spun the old Battery Productions Division into the Eveready Battery Company. In 1989 it launched the first of its Energizer bunny ads. Initially they did little to improve sales, but by 1992 the campaign had increased them by seven percent. In 1999, Purina rebranded Eveready as Energizer. In April 2000, shares of Energizer were placed on the stock market.

During his years with the company, Urry also invented a rechargeable nickel-cadmium battery, a magnesium one for military walkie-talkies, and a lithium one for cameras. He retired from Energizer in 2004, only to die a few months later on October 17, 2004. He was 77.🕜

In 1980, Eveready introduced the Energizer alkaline battery. In the era of the Walkman and other portable devices, there was plenty of room for two big producers of alkaline batteries, allowing Energizer to catch up with Duracell in terms of sales. In the 1980s, an epidemic of hostile takeovers by corporate raiders erupted on Wall Street. To inoculate itself against this possibility, Union Carbide sold its profitable battery division to the Ralston Purina Company, the pet food maker. This benefited Union Carbine by making it less profitable and thus not worth a corporate raider’s effort.

Purina paid a massive $1.4 billion for it, creating so much debt that it, too, became unattractive for a hostile takeover. Purina spun the old Battery Productions Division into the Eveready Battery Company. In 1989 it launched the first of its Energizer bunny ads. Initially they did little to improve sales, but by 1992 the campaign had increased them by seven percent. In 1999, Purina rebranded Eveready as Energizer. In April 2000, shares of Energizer were placed on the stock market.

During his years with the company, Urry also invented a rechargeable nickel-cadmium battery, a magnesium one for military walkie-talkies, and a lithium one for cameras. He retired from Energizer in 2004, only to die a few months later on October 17, 2004. He was 77.🕜

George Leclanché

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons