INVENTION OF THE CASH REGISTER

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

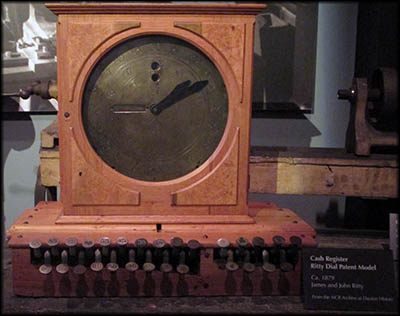

Ritty's Cash Register

Carillon Historic Park

Carillon Historic Park

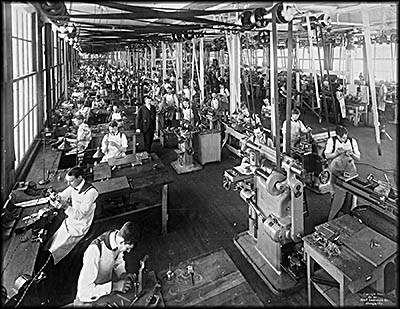

NCR's Tool Room in Dayton

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

NCR Cash Register Collection

Carillon Historic Park

Carillon Historic Park

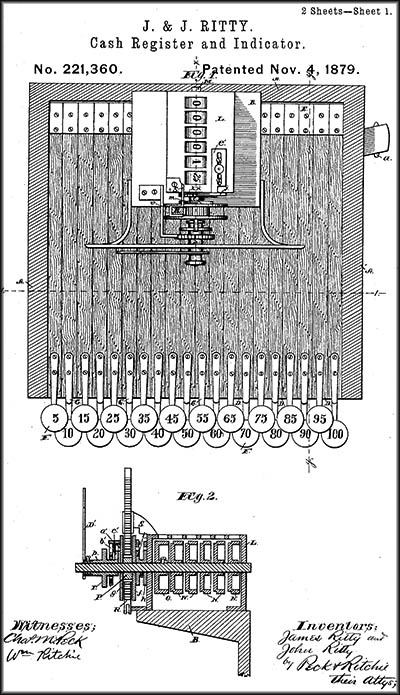

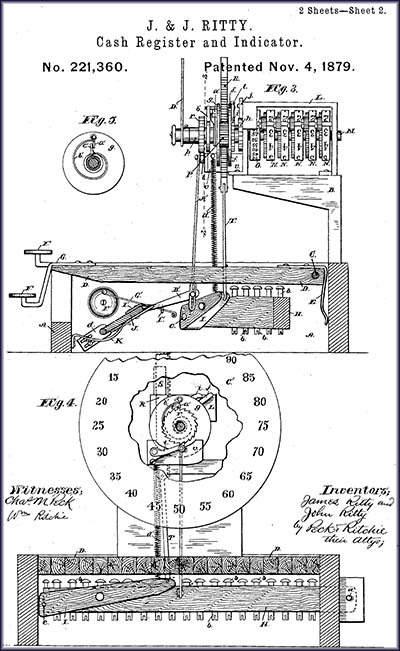

Original cash register patent taken out by James and John Ritty.

James “Jake” Ritty had a problem. In 1871 he’d taken over a Dayton saloon, but he found it hard to keep the place profitable because his employees kept pilfering his earnings and giving free drinks to their friends. Born in Cincinnati on October 29, 1836, Ritty moved to Dayton at the age of four. Reaching adulthood, he never planned to run a saloon. After graduating from high school, he attended medical school which he later quit to join the Union Army to fight in the Civil War. During this conflict, he reached the rank of captain, and returned to Dayton afterwards.

The losses at his saloon caused him so much stress, he decided to take a vacation to Europe in 1878 to avoid a mental breakdown. While sailing across the Atlantic on a steamer (another story says he was on a steamboat on a European river), he became friendly with chief engineer, who gave him a tour of the engine room. There Ritty saw an automated device using a series of gears to log the number of the vessel’s propeller revolutions. Maybe, he thought, he could use this to keep track of his sales at the saloon? Excited, he returned home early. His brother, John, was a mechanic, so he asked him to build a prototype. They brothers jointly filed for a patent that was issued on November 4, 1879.

Their invention, called Ritty’s Incorruptible Cashier, looked more like a clock than the modern cash register. It didn’t even have a cash drawer. Although some sources say a bell wasn’t added until later versions, the patent description mentions the existence of one on the machine. Its purpose was to alert the store owner that a sale had been made. To use the machine, a person pressed the appropriate cents keys that engaged discs within its chassis. A large dial on the front kept track of the day’s sales.

The losses at his saloon caused him so much stress, he decided to take a vacation to Europe in 1878 to avoid a mental breakdown. While sailing across the Atlantic on a steamer (another story says he was on a steamboat on a European river), he became friendly with chief engineer, who gave him a tour of the engine room. There Ritty saw an automated device using a series of gears to log the number of the vessel’s propeller revolutions. Maybe, he thought, he could use this to keep track of his sales at the saloon? Excited, he returned home early. His brother, John, was a mechanic, so he asked him to build a prototype. They brothers jointly filed for a patent that was issued on November 4, 1879.

Their invention, called Ritty’s Incorruptible Cashier, looked more like a clock than the modern cash register. It didn’t even have a cash drawer. Although some sources say a bell wasn’t added until later versions, the patent description mentions the existence of one on the machine. Its purpose was to alert the store owner that a sale had been made. To use the machine, a person pressed the appropriate cents keys that engaged discs within its chassis. A large dial on the front kept track of the day’s sales.

John Patterson

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Ritty began building his new cash registers on Dayton’s East 1st Street. Few wanted his new invention, so he sold out to Jacob H. Eckert of Cincinnati for $1,000. Eckert’s brother-in-law, a machinist named John Birch, added a cash drawer. To raise capital, Eckert formed the National Manufacturing Company and sold stock. Some of the shares were bought by brothers John and Francis “Frank” Patterson. Their interest came from personal experience. In 1882 James H. Patterson had purchased two cash registers for $50 each to see if it would help with the finances of the general store he and Frank ran that sold goods to miners in Coalton, Ohio. Business was good but profits weren’t. Employee theft caused the store to lose money. The cash registers reversed this in short order.

By 1884, National Manufacturing was failing. Demand for cash registers just hadn’t materialized. Convinced the cash register had a bright future despite what reality indicated, Patterson offered to buy out National Manufacturer’s president and biggest shareholder, George Phillips, for $6,500. The next day Patterson got cold feet and asked Phillips to annul the contract for $100. Additional offers of $500 and $2,000 failed to convince Phillips to reverse his decision, so Patterson told him he’d make the business a success and Phillips would regret it. On November 22, 1884, Patterson took over the company despite knowing nothing about manufacturing. He put Frank in charge of that part of the business.

By 1884, National Manufacturing was failing. Demand for cash registers just hadn’t materialized. Convinced the cash register had a bright future despite what reality indicated, Patterson offered to buy out National Manufacturer’s president and biggest shareholder, George Phillips, for $6,500. The next day Patterson got cold feet and asked Phillips to annul the contract for $100. Additional offers of $500 and $2,000 failed to convince Phillips to reverse his decision, so Patterson told him he’d make the business a success and Phillips would regret it. On November 22, 1884, Patterson took over the company despite knowing nothing about manufacturing. He put Frank in charge of that part of the business.

Patterson was born in Dayton on December 13, 1844. Although he graduated from the prestigious Dartmouth College in 1867, for many years none of his business ventures succeeded. This one would be different. In order to boost sales, he decided to create demand that didn’t exist. The was an entirely new concept in the history of advertising and marketing. He didn’t patent the idea, but that didn’t matter because no one wanted to steal it anyway. Most businessmen thought it was crazy.

To drum up demand, Patterson mailed sales materials to 5,000 saloon owners for eighteen days straight. The mailers worked so well, he kept sending them and expanded the target customers to drug and grocery store owners. Dishonest employees who knew the cash register would catch them out made sure anything with “National Cash Register” on it never made it to their bosses. Catching on to this, Patterson removed any indication of who was sending the mailers. Dishonest clerks retaliated by intercepting any mail postmarked from Dayton, so Patterson had his adverts mailed from other cities.

He assembled a team of salesmen and gave them exclusive territories. They earned no salary, just commissions. Any registers sold in a given territory went into the pocket of the person who controlled it, even if another NCR salesman made the sale. NCR salesmen were to directed to sell by showing the prospective purchaser (P.P.) how it would increase profits by keeping thieving employees from stealing their money.

To drum up demand, Patterson mailed sales materials to 5,000 saloon owners for eighteen days straight. The mailers worked so well, he kept sending them and expanded the target customers to drug and grocery store owners. Dishonest employees who knew the cash register would catch them out made sure anything with “National Cash Register” on it never made it to their bosses. Catching on to this, Patterson removed any indication of who was sending the mailers. Dishonest clerks retaliated by intercepting any mail postmarked from Dayton, so Patterson had his adverts mailed from other cities.

He assembled a team of salesmen and gave them exclusive territories. They earned no salary, just commissions. Any registers sold in a given territory went into the pocket of the person who controlled it, even if another NCR salesman made the sale. NCR salesmen were to directed to sell by showing the prospective purchaser (P.P.) how it would increase profits by keeping thieving employees from stealing their money.

NCR salesmen often found it difficult to see the owner of a business because employees would physically prevent them from entering the premises. Patterson’s brother-in-law, Joseph H. Crane, was a successful wallpaper salesman and it was he who suggested a remedy this issue: NCR salesmen should meet potential customers outside their place of business so they couldn’t get distracted. Hotels were the perfect place for this.

Sometimes when a cash register was introduced, clerks did everything they could to make it appear faulty. One buyer in Chicago who purchased sixteen detail adders—a more sophisticated version of the standard cash register—contacted Patterson to say he’d be returning them because they were defective. Patterson went to Chicago to investigate personally because he suspected the clerks weren’t using his machines properly. He hired two Pinkerton detectives to look into it, and they learned that the clerks were purposely putting the wrong amounts in. For many years afterward detectives were employed to make sure clerks used NCR cash registers correctly.

Patterson was no salesman, so when someone on his salesforce did especially well, he’d ask him what his secret was. One of his most successful ones said he made friends with the proprietor and clerks before bringing up the cash register. Patterson immediately told his other salesmen to do the same. He collected all this wisdom, put it into a book named the N.C.R. Primer, and made it required reading for his salesforce. The first version came out in June 1887. The idea for the Primer was inspired by Patterson’s brother-in-law, Crane. After coming to work for Patterson as an NCR salesman, he found it difficult to remember everything about the machine he now sold. So he wrote down what he needed to say and memorized it.

Sometimes when a cash register was introduced, clerks did everything they could to make it appear faulty. One buyer in Chicago who purchased sixteen detail adders—a more sophisticated version of the standard cash register—contacted Patterson to say he’d be returning them because they were defective. Patterson went to Chicago to investigate personally because he suspected the clerks weren’t using his machines properly. He hired two Pinkerton detectives to look into it, and they learned that the clerks were purposely putting the wrong amounts in. For many years afterward detectives were employed to make sure clerks used NCR cash registers correctly.

Patterson was no salesman, so when someone on his salesforce did especially well, he’d ask him what his secret was. One of his most successful ones said he made friends with the proprietor and clerks before bringing up the cash register. Patterson immediately told his other salesmen to do the same. He collected all this wisdom, put it into a book named the N.C.R. Primer, and made it required reading for his salesforce. The first version came out in June 1887. The idea for the Primer was inspired by Patterson’s brother-in-law, Crane. After coming to work for Patterson as an NCR salesman, he found it difficult to remember everything about the machine he now sold. So he wrote down what he needed to say and memorized it.

The combination of well-trained salesforce and direct mail advertising worked. It made Patterson a millionaire, and an eccentric one at that. When Stanley C. Allyn decided to leave home in Wisconsin to go work for NCR upon graduating from college in 1913, his father warned, “You’ll never been able to work for Patterson … The man’s a lunatic.” This was not hyperbole. Patterson married for the first time at the age of 44. When his wife, Katharine Beck, died six years later, he was left with two children he couldn’t cope with, so he sent them off to his sister and barely participated in their lives. His legendary hypochondria prompted him to have a personal physician on hand at NCR. He became obsessed with food fads and often foisted them upon his employees, such as the hot water diet. He also banned salt and pepper from the NCR lunchroom and insisted baked potatoes be on the menu nearly all the time.

Allyn decided working for Patterson in Dayton was still preferrable to Wisconsin because it allowed him to escape his puritanical mother. He had to work Monday through Friday from 6:30 in the morning to 5:15 in the afternoon, and till noon on Saturdays. Although employees weren’t forced, it was advisable for one’s career to do ten minutes of calisthenics each day. Patterson sent a flurry of memos and gave lectures about how employees ought how to live their lives. Tobacco and demon rum, for example, were discouraged.

While Ritty never profited from his invention, he hardly died destitute. In his later years, he invested in Dayton’s Pony House on South Jefferson Street. This was both a hotel and where the city’s sporting fraternity gathered. He retired from this venture fourteen years before his death from heart failure on March 29, 1918. Ritty became good friends with the Patterson brothers and sometimes attended conferences and meetings at NCR.🕜

Allyn decided working for Patterson in Dayton was still preferrable to Wisconsin because it allowed him to escape his puritanical mother. He had to work Monday through Friday from 6:30 in the morning to 5:15 in the afternoon, and till noon on Saturdays. Although employees weren’t forced, it was advisable for one’s career to do ten minutes of calisthenics each day. Patterson sent a flurry of memos and gave lectures about how employees ought how to live their lives. Tobacco and demon rum, for example, were discouraged.

While Ritty never profited from his invention, he hardly died destitute. In his later years, he invested in Dayton’s Pony House on South Jefferson Street. This was both a hotel and where the city’s sporting fraternity gathered. He retired from this venture fourteen years before his death from heart failure on March 29, 1918. Ritty became good friends with the Patterson brothers and sometimes attended conferences and meetings at NCR.🕜