Johnston Farm and Indian Agency

Johnston Family House

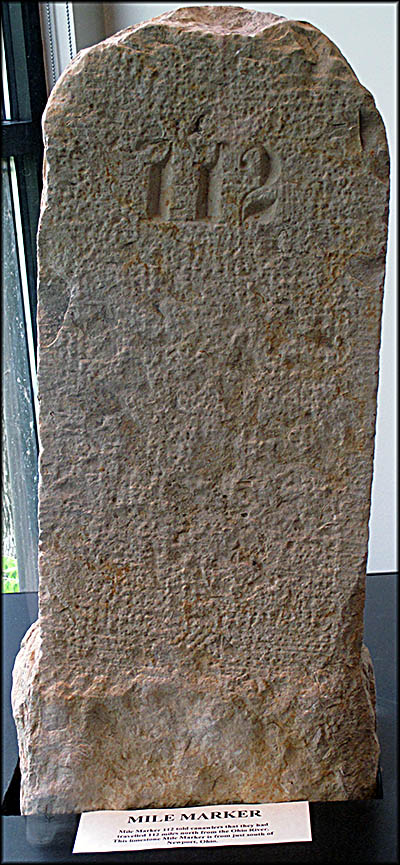

Canal Mile Marker

Images of the canal and canal boat.

I’ve been wanting to visit the Johnston Farm and Indian Agency for quite a few years but never got around to it because of its short season. It’s a farm once owned by John Johnston and is only open to the general public in June, July and August. Being run by the chronically underfunded Ohio History Connection, I was surprised how much work was recently done to the Johnston house. It had been restored to its original Federal style after its interior was incorrectly given a Victorian look in the 1960s. There is also a small museum on the grounds that was having its exterior remodeled.

Upon arrival, I was delighted to learn that the modest entry fee I paid to get in included a ride on the nearby working section of the Miami and Erie Canal. The first ride of the day was set to begin shortly after my traveling companion and I got there, so down to the canal we went. Along its side floated the General Harrison of Piqua, which was certified by the American Canal Society (who knew it existed?) in 2009. I wrote about the Ohio and Erie Canal in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio, so I was excited to have my first ride in a canal boat. Except it wasn’t. My mother, who had come with me on this trip, informed me I’d ridden in one before when I was quite young. But if you can’t remember it, does it really count?

In the earliest day of America, boats were pulled by beasts of burden. In our case, mules provided the power. As we cruised at a speedy two miles per hour, our guide gave us some of the history of Ohio’s canal system in general and the Miami and Erie Canal in particular. Started in 1825, the Miami and Erie Canal was the brainchild of businessmen in Cincinnati. They predicted a canal connecting their town to Lake Erie would help grow its economic development. When Cincinnati businessman Ethan Allen Brown became Ohio’s governor in 1818, he got the state legislature to make this idea a reality. With money tight, in 1825 the legislature was only able to fund a section of the proposed canal from Cincinnati to Dayton, although plans were laid to continue it all the way to Lake Erie. This first section was completed in 1829, and it benefited Dayton so much that it tried to block the canal’s extension farther northward. Affected communities through which the canal was planned to go fought that, and in the end it was none other than John Johnston who led the campaign to resume the canal’s construction. Work restarted in 1833 and was completed in 1845. The canal spanned 248.8 miles and rose to an elevation of 512 feet above Lake Erie.

All of Ohio’s canals had the same width and depth, measurements borrowed from New York’s Erie Canal. The entirety of the Miami and Erie Canal was dug by hand using picks, axes, shovels, and some black powder—an amazing accomplishment. Although local farmers did some of the labor as a means to earn extra income, their numbers weren’t nearly enough to do the work, so German and Irish immigrants were brought in. Irish and Germans didn’t get along, so they had to be kept separated. The backbreaking labor these immigrants did paid little and involved working from sun up to sun down. Outbreaks of diseases such as cholera and malaria at times devastated this workforce. Those workers who died were buried under the towpath, meaning any time you walk on it, you’re stepping over graves. One outbreak of disease in 1827 got so bad, Ohio was forced to use convict labor to keep the work going. Another epidemic in 1829 prompted many of the workers to skedaddle.

In the earliest day of America, boats were pulled by beasts of burden. In our case, mules provided the power. As we cruised at a speedy two miles per hour, our guide gave us some of the history of Ohio’s canal system in general and the Miami and Erie Canal in particular. Started in 1825, the Miami and Erie Canal was the brainchild of businessmen in Cincinnati. They predicted a canal connecting their town to Lake Erie would help grow its economic development. When Cincinnati businessman Ethan Allen Brown became Ohio’s governor in 1818, he got the state legislature to make this idea a reality. With money tight, in 1825 the legislature was only able to fund a section of the proposed canal from Cincinnati to Dayton, although plans were laid to continue it all the way to Lake Erie. This first section was completed in 1829, and it benefited Dayton so much that it tried to block the canal’s extension farther northward. Affected communities through which the canal was planned to go fought that, and in the end it was none other than John Johnston who led the campaign to resume the canal’s construction. Work restarted in 1833 and was completed in 1845. The canal spanned 248.8 miles and rose to an elevation of 512 feet above Lake Erie.

All of Ohio’s canals had the same width and depth, measurements borrowed from New York’s Erie Canal. The entirety of the Miami and Erie Canal was dug by hand using picks, axes, shovels, and some black powder—an amazing accomplishment. Although local farmers did some of the labor as a means to earn extra income, their numbers weren’t nearly enough to do the work, so German and Irish immigrants were brought in. Irish and Germans didn’t get along, so they had to be kept separated. The backbreaking labor these immigrants did paid little and involved working from sun up to sun down. Outbreaks of diseases such as cholera and malaria at times devastated this workforce. Those workers who died were buried under the towpath, meaning any time you walk on it, you’re stepping over graves. One outbreak of disease in 1827 got so bad, Ohio was forced to use convict labor to keep the work going. Another epidemic in 1829 prompted many of the workers to skedaddle.

Once built, operating and maintaining the canal was its own challenge. Lock operators were on call twenty-four hours a day. Someone had to take care of the livestock that towed canalboats, and others had to walk the beasts of burden down the towpath. Traffic tended to back up at locks, so the small towns that grew up around them became rowdy places because crews would go drinking in them while waiting for their boat to pass through.

By the time the Miami and Erie Canal was completed in 1845, it was already obsolete because of the railroads. The first one to operate in the United States was the Baltimore and Ohio, which began running in 1827. Although trains are for more efficient than canals, for decades Ohio’s canals were profitable. They transformed the state into an agricultural powerhouse. But wear and tear on them caused parts to shut down. The great flood of 1913 forced the last of Ohio’s operating canals to close permanently.

That the Miami and Erie Canal went through Johnston’s farm was no accident. He was, after all, one of the commissioners appointed to oversee it in 1825. Even had he not been involved, the Great Miami River that flowed through his land was too good a source of water to ignore. Although he is a not a well known historical figure today, in his day he was a powerful man in Ohio. He was good friends with William Henry Harrison, who was elected president in 1840.

By the time the Miami and Erie Canal was completed in 1845, it was already obsolete because of the railroads. The first one to operate in the United States was the Baltimore and Ohio, which began running in 1827. Although trains are for more efficient than canals, for decades Ohio’s canals were profitable. They transformed the state into an agricultural powerhouse. But wear and tear on them caused parts to shut down. The great flood of 1913 forced the last of Ohio’s operating canals to close permanently.

That the Miami and Erie Canal went through Johnston’s farm was no accident. He was, after all, one of the commissioners appointed to oversee it in 1825. Even had he not been involved, the Great Miami River that flowed through his land was too good a source of water to ignore. Although he is a not a well known historical figure today, in his day he was a powerful man in Ohio. He was good friends with William Henry Harrison, who was elected president in 1840.

The Johnston House with a view of the courtyard.

Johnston was born in Ireland on March 25, 1775. Although descended from French Huguenots, he was an Episcopalian. He came to America at the age of ten or eleven in 1786 and settled with his family in Philadelphia. As a young man, he traveled to the Northwest Territory, and from 1792 to 1795, took charge of supplying General Anthony Wayne’s army in Ohio to deal with tensions and fighting with the native population. In 1795, Johnston briefly traveled with Daniel Boone. He returned to Philadelphia in 1799 where for about a year he boarded with a family of Quakers. In 1782, he eloped with Rachel Robinson, a young Quaker woman.

The newlyweds headed to Fort Wayne, Indiana, where Johnston became the factor for the newly established Indian agency there. A factor was in charge of the commercial relations between Native Americans and the U.S. government. There was also an Indian agent who dealt with political relations. General Wayne finally subdued Ohio’s native people at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, then forced them to sign the Treaty of Greene Ville (or Greenville) in 1795. Afterward, Ohio’s Native Americans wanted to settle down to become farmers, so in his capacity as factor, Johnson began selling them agricultural implements.

In 1804, he found the perfect place to build a house and farm, so he had a land agent purchase it when it became available. He planned to become a “gentleman farmer.” In addition to running his farm, he worked for the War Department off and on for years, and from 1809 to 1811 served as both the factor and Indian agent at Fort Wayne.

He had a two-story log cabin constructed on his land into which he moved his growing family in 1811. Here they stayed until the brick farm house that stands there today was completed in August 1815. These years weren’t without trouble. In 1812, the U.S. went to war with Britain, a conflict that soon drew in the region’s Native Americans. Johnston secured pledges of neutrality from some of them, hundreds of whom lived on his farm during the war.

The newlyweds headed to Fort Wayne, Indiana, where Johnston became the factor for the newly established Indian agency there. A factor was in charge of the commercial relations between Native Americans and the U.S. government. There was also an Indian agent who dealt with political relations. General Wayne finally subdued Ohio’s native people at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, then forced them to sign the Treaty of Greene Ville (or Greenville) in 1795. Afterward, Ohio’s Native Americans wanted to settle down to become farmers, so in his capacity as factor, Johnson began selling them agricultural implements.

In 1804, he found the perfect place to build a house and farm, so he had a land agent purchase it when it became available. He planned to become a “gentleman farmer.” In addition to running his farm, he worked for the War Department off and on for years, and from 1809 to 1811 served as both the factor and Indian agent at Fort Wayne.

He had a two-story log cabin constructed on his land into which he moved his growing family in 1811. Here they stayed until the brick farm house that stands there today was completed in August 1815. These years weren’t without trouble. In 1812, the U.S. went to war with Britain, a conflict that soon drew in the region’s Native Americans. Johnston secured pledges of neutrality from some of them, hundreds of whom lived on his farm during the war.

On March 5, 1812, Johnston became the Indian Agent for the Shawnees and Wapakoneta. He served as the Indian agent for all of Ohio from 1816 to 1829. Being a Whig, he was fired when Andrew Jackson became president. Jackson hated Native Americans with such passion he exiled nearly all of them west of the Mississippi, and this included Ohio’s population. In 1842, negotiations for the removal of last of the tribe to depart the state, the Wyandots, were led by Johnston.

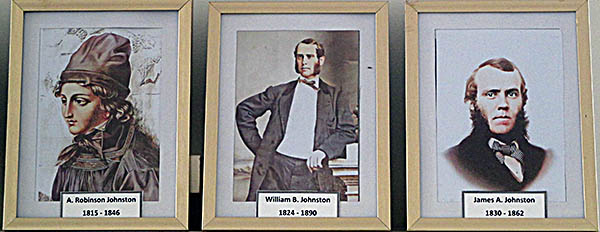

Portraits of some of John Johnston's children.

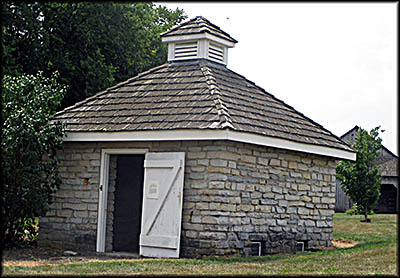

Throughout his long life—he lived to the ripe old age of eighty-five, expiring on February, 18, 1861—Johnston experienced periods of great middle class prosperity as well as lean times. In his spare time, he helped found Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio. His house was built in two sections, the room needed for the fourteen of his fifteen children who survived to adulthood. His barn, built in 1808, still stands today, as does his cider house (built in October 1829) and the springhouse (built in 1810–1811). The powerful spring this last structure stands upon provides all the water for the section of the Miami and Erie Canal on the property. In the springhouse’s upper story you’ll find spinning wheels and a giant loom, although in Johnston’s day it probably just housed servants.

In the kitchen there is a fireplace discovered during the house’s recent restoration. Here Johnston’s wife, Rachel, did all the cooking herself. She also refused to have a stove, and even turned her nose down at the fact that one of her daughter’s had one.

After visiting the house, my mother and I headed to the museum, which is roughly half way between the house and canal. Although it contains information about Johnston and the Miami and Erie Canal, the most informative section is where it discusses Ohio’s historic native people. This begins with the trade of furs. The Iroquois Confederacy, located mainly in what is now upstate New York State, Ontario and Quebec, did well with this, but the mid-seventeenth century, the Confederacy had exhausted its territory's supply of desirable furry animals. This prompted the Iroquois to invade what is now the State of Ohio where a plentiful supply of furry animals roamed, forcing the Petuns, Wyandots, Sisquehannocks and Eries to move west and breaking up the alliance of Shawnees, Wyandots and Eries. The resulting conflict between the Iroquois and those already living in the region became known as the Beaver Wars. This conflict in 1701 when the Iroquois, French and British signed the Treaty of Grand Paix (Great Peace), which allowed those tribes pushed out the region to return.

In the kitchen there is a fireplace discovered during the house’s recent restoration. Here Johnston’s wife, Rachel, did all the cooking herself. She also refused to have a stove, and even turned her nose down at the fact that one of her daughter’s had one.

After visiting the house, my mother and I headed to the museum, which is roughly half way between the house and canal. Although it contains information about Johnston and the Miami and Erie Canal, the most informative section is where it discusses Ohio’s historic native people. This begins with the trade of furs. The Iroquois Confederacy, located mainly in what is now upstate New York State, Ontario and Quebec, did well with this, but the mid-seventeenth century, the Confederacy had exhausted its territory's supply of desirable furry animals. This prompted the Iroquois to invade what is now the State of Ohio where a plentiful supply of furry animals roamed, forcing the Petuns, Wyandots, Sisquehannocks and Eries to move west and breaking up the alliance of Shawnees, Wyandots and Eries. The resulting conflict between the Iroquois and those already living in the region became known as the Beaver Wars. This conflict in 1701 when the Iroquois, French and British signed the Treaty of Grand Paix (Great Peace), which allowed those tribes pushed out the region to return.

The Miami, who called themselves Myaamiaki and lived in the Detroit area, began migrating south in 1708, settling along the Maumee River and as far west as modern Fort Wayne. Between 1747 and 1752, a group of them established the village of Pickawillany near modern day Piqua, Ohio. Led by the Miami chief Memeksia (called “La Demoiselle” by the French and “Old Britain” by the English), it became a trading post for the British. The trouble was the French considered this their territory and took offense to British traders encroaching into their sphere of influence.

The French also feared that Memeksia was plotting a revolt, so they sent Charles Langlade to deal with the problem. The son of a Frenchman and Native American woman, Langlade led a force of about 250 Chippewas, Ottawas, and French-Canadians in a surprise attack on Pickawillany on June 21, 1752. Most the settlement’s warriors were off hunting, leaving behind woman, children and British traders. A short fight ensued during which several died, but the defenders were no match for the attacking force and quickly surrendered. The British traders here were made prisoners and brought to Fort Detroit. Pickawillany was destroyed. This attack was a prelude to the French and Indian War that would start two years later.

The French also feared that Memeksia was plotting a revolt, so they sent Charles Langlade to deal with the problem. The son of a Frenchman and Native American woman, Langlade led a force of about 250 Chippewas, Ottawas, and French-Canadians in a surprise attack on Pickawillany on June 21, 1752. Most the settlement’s warriors were off hunting, leaving behind woman, children and British traders. A short fight ensued during which several died, but the defenders were no match for the attacking force and quickly surrendered. The British traders here were made prisoners and brought to Fort Detroit. Pickawillany was destroyed. This attack was a prelude to the French and Indian War that would start two years later.

Between 1730 and 1750, the Lenapes moved into Ohio. They were called the Delaware by the British because they originally lived along the Delaware River—a name given to it by English settlers. The Lenapes got along well with the Shawnees, whose eastern and western factions moved into Ohio in the 1730s and 1740s, merging into one nation by 1750.

The Wyandots, who the English called the Hurons, came south from Detroit and settled around Sandusky Bay in the 1730s. From here they spread out, their southernmost settlement being Conchake about where Coshocton is today. The Ottawas, close allies to the Wyandots despite having a different language, also came south from the Detroit area. The Mingo settled along the Ohio River. This group was made up of members of the Senecas, Mohawks and Cayugas, all formally part of the Iroquois Confederacy.

The Wyandots, who the English called the Hurons, came south from Detroit and settled around Sandusky Bay in the 1730s. From here they spread out, their southernmost settlement being Conchake about where Coshocton is today. The Ottawas, close allies to the Wyandots despite having a different language, also came south from the Detroit area. The Mingo settled along the Ohio River. This group was made up of members of the Senecas, Mohawks and Cayugas, all formally part of the Iroquois Confederacy.

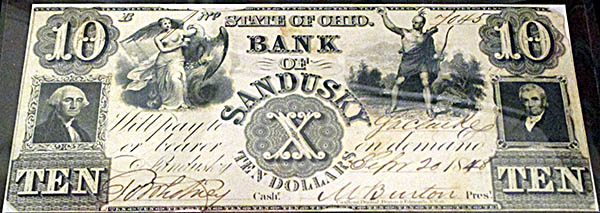

This bill printed for the Bank of Sandusky has a drawing of a Native American that perpetuated stereotypes.

Over the years I’ve visited recreated Native American settlements in Ohio and it drives me crazy that many have teepees. The Native Americans who settled in Ohio in the eighteenth century never lived in teepees or anything resembling them. For a quick overnight shelter, they used a lean-to. The closest thing they had to a teepee was the dome-shaped wigwam. The Lenape brought to Ohio the long house, a structure that was typically twenty feet wide and 100 feet long in which several families lived. Some native people even built log cabins.

While the museum does an excellent job at outlining the history of Ohio’s native people from about 1750 to 1840, it does have some missteps. For one, it lumps all of Ohio’s tribes into one group known as the “Woodland people,” as if they were a monolithic group whose differences were minor. Worse, one sign had this sweeping generalization about them: “There was almost no distinction between myth and actuality. The Woodland people interpreted themselves and their world through dreams. They marked their seasonal ceremonies.” This isn’t very useful because nearly every culture on the earth has these characteristics. Europeans in that era burned witches and depended on fortune tellers, divination, and all sorts of “magic” that was no more grounded in science than anything Native Americans believed. Europeans were keen readers of the Bible in which Joseph interpreted the dreams of Pharoah in the Book of Genesis. And Europeans had their own seasonal ceremonies such as Christmas, Easter, Summer Solstice, and Halloween.

Despite this criticism, I can’t praise this site enough. The guides were interesting and well-informed, and the historic buildings—all originals—give the visitor a good idea of what living on a farm run by a middle class family in the first half of nineteenth century was like. But be warned. The farm is 250 acres, meaning there is a lot of walking. Comfortable shoes are recommended.🕜

While the museum does an excellent job at outlining the history of Ohio’s native people from about 1750 to 1840, it does have some missteps. For one, it lumps all of Ohio’s tribes into one group known as the “Woodland people,” as if they were a monolithic group whose differences were minor. Worse, one sign had this sweeping generalization about them: “There was almost no distinction between myth and actuality. The Woodland people interpreted themselves and their world through dreams. They marked their seasonal ceremonies.” This isn’t very useful because nearly every culture on the earth has these characteristics. Europeans in that era burned witches and depended on fortune tellers, divination, and all sorts of “magic” that was no more grounded in science than anything Native Americans believed. Europeans were keen readers of the Bible in which Joseph interpreted the dreams of Pharoah in the Book of Genesis. And Europeans had their own seasonal ceremonies such as Christmas, Easter, Summer Solstice, and Halloween.

Despite this criticism, I can’t praise this site enough. The guides were interesting and well-informed, and the historic buildings—all originals—give the visitor a good idea of what living on a farm run by a middle class family in the first half of nineteenth century was like. But be warned. The farm is 250 acres, meaning there is a lot of walking. Comfortable shoes are recommended.🕜

John Johnston

Ohio Memory

Ohio Memory

Inside the Johnston House

Johnston House's Dining Room

Boy's Bedroom in the Johnston House

Johnston Barn

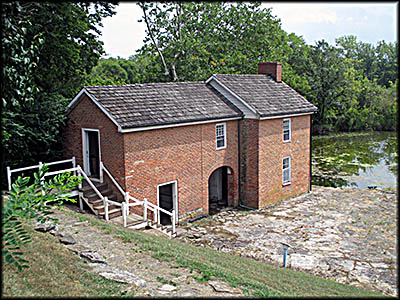

Cider House

Spring House

Inside the Spring House

General Anthony Wayne

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Inside the Museum