THE LAST GAMBIT

THE LAST GAMBIT

Copyright © 2012 by Mark Strecker.

Duncan Farrar Kenner

Tennessee Portrait Project

Tennessee Portrait Project

The Jefferson Davis Mansion, Richmond, Virginia

This is where Benjamin and Davis proposed the secret mission to Kenner.

Library of Congress

This is where Benjamin and Davis proposed the secret mission to Kenner.

Library of Congress

Duncan Farrar Kenner had an epiphany shortly after escaping the Union soldiers who had invaded and confiscated his sugarcane plantation near New Orleans. It occurred to him that slavery in the South had met its end and the Confederacy could do nothing to save it. He believed the South should emancipate all of its slaves so as to gain official recognition as well as financial help from European powers, especially France and England, who had long ago outlawed slavery on moral grounds.

Judah P. Benjamin, Secretary of State for the Confederacy

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

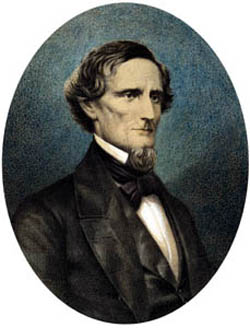

Jefferson Davis

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Emperor Napoleon III

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

John Sildell

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

James P. Mason

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

A dour fellow who lacked any hair, Kenner had amassed a vast fortune generated by real estate speculation and his plantations. Born on February 11, 1813, in New Orleans, his family sent him to Miami University in Ohio, then on a two-year tour of Europe. Upon his return to New Orleans, he studied law, working for and befriending John Slidell. A few years later he left law to run his plantation in Ascension Parish with his brother George. There he pursued his hobbies of gambling (thinking nothing of losing $20,000 in one night), and raising thoroughbred horses while his brother spent much of his free time wooing Charlotte Jones, his slave lover, with whom he fathered seven children. When George sold his interest in the plantation, he freed Charlotte and four of their children.

Duncan had trained one of those not freed to raise thoroughbred horses. Charlotte offered to buy him for $2,000, but the heartless Kenner refused; his nephew’s skills at horse rearing made him far too valuable to sell for such a paltry sum. He wanted $3,400. This amount would have wiped out Charlotte’s entire savings, so she countered with an offer of $2,500. Kenner agreed to take this, but only on the condition that his nephew stay in bondage for three more years, earning wages to make up the difference in price.

During the Civil War, Kenner served as a member of the Confederate House of Representatives, the last incumbency in his political career. Always the gambler, he joined whatever party would serve his interests best. Originally a Democrat, he ran for his first office as a Whig. When that party imploded, he switched to the anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant Know-Nothing Party. And when that collapsed, he returned to the Democratic Party.

After the flight from his plantation, he proposed his idea of freeing slaves to gain European favor to Jefferson Davis, but the Confederate president wanted nothing to do with it and asked him not to put this forward in the Confederate House. Two years later, as Grant closed in on Richmond and it became obvious the Confederacy had to do something radical or it would soon fall, Davis’ secretary of state, Judah P. Benjamin, remembered Kenner’s idea. Based on it, he formulated a plan. Davis should send a diplomatic mission to England and France asking for economic and military support against the North in exchange for vast quantities of cotton. To erase any moral objections either foreign government might have, the Confederacy would offer to emancipate all its slaves. To gain the time the it would need for an envoy to make the proposal and, if successful, for foreign aid to reach the besieged South, Benjamin recommended arming slaves to bolster the Confederate Army. For this service they would earn their freedom.

Davis resisted the first idea, believing he lacked the authority to free a single slave to gain foreign favor. When Benjamin pointed out that as commander-in-chief of the South’s armed forces, he could order it as a military necessity, Davis concurred, but with the caveat that only gradual emancipation would do. As for the second idea (making slaves soldiers and offering them their freedom as a reward), Davis had suggested this very possibility a month earlier in a congressional message. He decided not to ask the Confederate Congress to authorize it unless Robert E. Lee himself made the request. Davis knew that without Lee’s advocacy, the Confederate Congress would never go along with it. When Lee did so, Davis asked for and got legislation passed that allowed for the recruitment of slaves as soldiers. It passed in mid-March 1865, although it did not necessarily free slaves who gave their military service.

Now Benjamin and Davis faced a different problem: to whom could they entrust the mission? The two Confederate diplomats currently in Britain and France, John Slidell and James M. Mason, would not do. Both men vehemently supported slavery. Slidell had once involved himself with an illegal private venture to conquer Cuba with the idea of expanding American slavery there, while Mason had helped to pen the notorious Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Mason in any case had no ability to act as a diplomat. Statesman John Bigelow offered this opinion of him in an article written for the March 1891 issue of The Century Magazine: “The average school-girl of sixteen was about as well-qualified as Mason to cope with the bankers of London and Paris, the only foreign powers with which he seems to have had any intercourse or negotiations that amounted to anything.”

Davis and Benjamin decided to ask Kenner to become their envoy. They figured no one would object to this choice since Kenner owned more slaves than any one of his fellow legislators in the Confederate Congress, and thus had more to lose than anyone else if the gambit succeeded. When Benjamin asked Kenner, he initially declined, only agreeing after the Confederate secretary of state talked him into it. To ensure Slidell and Mason went along with the plan, Davis made Kenner an envoy extraordinaire and minister plenipotentiary, giving him complete authority over the other Confederate diplomats in Europe. In addition to the emancipation issue, Kenner had a secondary mission: he would establish a Franco-Confederate bank to help ease the South’s financial crisis, selling bales of cotton at fifty cents a pound to raise its initial capital.

Duncan had trained one of those not freed to raise thoroughbred horses. Charlotte offered to buy him for $2,000, but the heartless Kenner refused; his nephew’s skills at horse rearing made him far too valuable to sell for such a paltry sum. He wanted $3,400. This amount would have wiped out Charlotte’s entire savings, so she countered with an offer of $2,500. Kenner agreed to take this, but only on the condition that his nephew stay in bondage for three more years, earning wages to make up the difference in price.

During the Civil War, Kenner served as a member of the Confederate House of Representatives, the last incumbency in his political career. Always the gambler, he joined whatever party would serve his interests best. Originally a Democrat, he ran for his first office as a Whig. When that party imploded, he switched to the anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant Know-Nothing Party. And when that collapsed, he returned to the Democratic Party.

After the flight from his plantation, he proposed his idea of freeing slaves to gain European favor to Jefferson Davis, but the Confederate president wanted nothing to do with it and asked him not to put this forward in the Confederate House. Two years later, as Grant closed in on Richmond and it became obvious the Confederacy had to do something radical or it would soon fall, Davis’ secretary of state, Judah P. Benjamin, remembered Kenner’s idea. Based on it, he formulated a plan. Davis should send a diplomatic mission to England and France asking for economic and military support against the North in exchange for vast quantities of cotton. To erase any moral objections either foreign government might have, the Confederacy would offer to emancipate all its slaves. To gain the time the it would need for an envoy to make the proposal and, if successful, for foreign aid to reach the besieged South, Benjamin recommended arming slaves to bolster the Confederate Army. For this service they would earn their freedom.

Davis resisted the first idea, believing he lacked the authority to free a single slave to gain foreign favor. When Benjamin pointed out that as commander-in-chief of the South’s armed forces, he could order it as a military necessity, Davis concurred, but with the caveat that only gradual emancipation would do. As for the second idea (making slaves soldiers and offering them their freedom as a reward), Davis had suggested this very possibility a month earlier in a congressional message. He decided not to ask the Confederate Congress to authorize it unless Robert E. Lee himself made the request. Davis knew that without Lee’s advocacy, the Confederate Congress would never go along with it. When Lee did so, Davis asked for and got legislation passed that allowed for the recruitment of slaves as soldiers. It passed in mid-March 1865, although it did not necessarily free slaves who gave their military service.

Now Benjamin and Davis faced a different problem: to whom could they entrust the mission? The two Confederate diplomats currently in Britain and France, John Slidell and James M. Mason, would not do. Both men vehemently supported slavery. Slidell had once involved himself with an illegal private venture to conquer Cuba with the idea of expanding American slavery there, while Mason had helped to pen the notorious Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Mason in any case had no ability to act as a diplomat. Statesman John Bigelow offered this opinion of him in an article written for the March 1891 issue of The Century Magazine: “The average school-girl of sixteen was about as well-qualified as Mason to cope with the bankers of London and Paris, the only foreign powers with which he seems to have had any intercourse or negotiations that amounted to anything.”

Davis and Benjamin decided to ask Kenner to become their envoy. They figured no one would object to this choice since Kenner owned more slaves than any one of his fellow legislators in the Confederate Congress, and thus had more to lose than anyone else if the gambit succeeded. When Benjamin asked Kenner, he initially declined, only agreeing after the Confederate secretary of state talked him into it. To ensure Slidell and Mason went along with the plan, Davis made Kenner an envoy extraordinaire and minister plenipotentiary, giving him complete authority over the other Confederate diplomats in Europe. In addition to the emancipation issue, Kenner had a secondary mission: he would establish a Franco-Confederate bank to help ease the South’s financial crisis, selling bales of cotton at fifty cents a pound to raise its initial capital.

Kenner wished to bring with him a document containing detailed instructions including the terms of any negotiations he would make. Benjamin refused. If the Union ever discovered it, this would doom the mission. For that matter, if it even gained a hint of this plan, Kenner would probably find it impossible to run its naval blockade and get to Europe. As a compromise, Benjamin gave Kenner a one page document that bestowed upon him power over Slidell and Mason as well as the authority to negotiate with foreign governments on behalf of the Confederate government. Kenner received an additional document containing details about the conditions for the sale of Southern cotton.

Around January 12, 1865, Kenner headed southeast to the last open Southern port at Wilmington, North Carolina. From here he planned to catch a blockade runner to Cuba and from there take a ship to Europe. A Union naval force intent on taking the Confederate-held Fort Fisher at Wilmington arrived first. Kenner stayed until the fortress surrendered in mid-January. Its commander, General Bragg, suggested he head to Charleston, South Carolina, and from there try to make his way to Europe. Figuring this would take too much time and likely result in failure, he retreated to Richmond.

Here he conceived of a risky plan. Rather than shipping out on a blockade runner, he would sneak north to New York City, and from there take a steamer to England. Although Davis and Benjamin did not like this plan, they agreed. He departed on the night of January 18, 1865, accompanied by two Confederate Secret Service officers, Howell and Merrick. He planned to catch a train to Baltimore out of Washington, D.C., and from there take another north to New York City. His two companions had no notion of his identity; they only knew him as a Confederate spy named A.B. Kinglake, supposedly destined for Canada.

Realizing that every big gambler in the country would recognize him, he disguised himself. He donned spectacles, grew out his beard, and likely wore a brown wig to cover his bald pate. The small group stalled at the Potomac, which abnormally foul weather had caused to partially freeze. Attempting to cross it could result in getting trapped by the ice, at which point a patrolling Union gunboat would find them an easy target. They waited three days before making their first attempt, and this failed. The next endeavor succeeded, although the weather had not improved.

The three made their way to a plantation house on the outskirts of Washington, D.C., owned by a family of Southern sympathizers. How Kenner and his companions got there remains debatable as two contradicting accounts exist. At this point either one of Kenner’s Secret Service companions procured horses, or the three men trudged through high snow drifts on foot until they reached their goal. The family living there drove the Kenner party to a nearby village in which Kenner spent $80 in gold for an old carriage and a few horses. At or around this moment he sent Merrick home.

He and his remaining companion headed to still another house of Southern sympathizers. Here Howell instructed Kenner to turn over all his money and papers to a young lady living within. Kenner reluctantly did so. The next morning Howell, who had quartered elsewhere, explained the reason for this. The young woman had placed all of Kenner’s articles upon her person as a means of keeping them safe. If Union officials came and searched the house and its occupants—something that occurred here from time to time—they would never intimately examine a young lady. She gave Kenner his possessions back.

He and Howell next headed to the Surratt house (from which members of this family had become involved with a plot to kidnap and then assassinate President Lincoln), only to find the Surratts had moved away. Kenner and Howell had no choice but to stay overnight in the woods. The next day they caught a train to Baltimore. On board they sat far apart, one planning to deny knowing the other if captured. The two rode in a non-smoking car since mainly rural folk used it, reducing the chances of anyone recognizing Kenner. In Baltimore, Kenner had an hour wait until boarding a train for Philadelphia. He passed the time shopping, buying and dressing in garb that made him look like a Pennsylvanian farmer. At this point Howell left for home, believing his cohort now planned to head straight for Canada.

Kenner arrived in New York City without incident. He took a room at the Metropolitan Hotel, an establishment he did not like because he feared the black waiters working there might recognize him (demonstrating his notoriety as a slave master). When he learned that Henry Stuart Foote, a former senator from Mississippi who had fled north at the outbreak of the war, lived in the hotel, he retreated to his room to avoid being recognized. He wrote a vague note to D.M. Hildreth, an old friend and the co-owner of the New York Hotel. He stated he had something to give Hildreth, but he could only do so in person. Would Hildreth please come see him? He signed the note as “A.B. Kinglake,” telling Hildreth that while he might not recognize the name, he would know the person.

Around January 12, 1865, Kenner headed southeast to the last open Southern port at Wilmington, North Carolina. From here he planned to catch a blockade runner to Cuba and from there take a ship to Europe. A Union naval force intent on taking the Confederate-held Fort Fisher at Wilmington arrived first. Kenner stayed until the fortress surrendered in mid-January. Its commander, General Bragg, suggested he head to Charleston, South Carolina, and from there try to make his way to Europe. Figuring this would take too much time and likely result in failure, he retreated to Richmond.

Here he conceived of a risky plan. Rather than shipping out on a blockade runner, he would sneak north to New York City, and from there take a steamer to England. Although Davis and Benjamin did not like this plan, they agreed. He departed on the night of January 18, 1865, accompanied by two Confederate Secret Service officers, Howell and Merrick. He planned to catch a train to Baltimore out of Washington, D.C., and from there take another north to New York City. His two companions had no notion of his identity; they only knew him as a Confederate spy named A.B. Kinglake, supposedly destined for Canada.

Realizing that every big gambler in the country would recognize him, he disguised himself. He donned spectacles, grew out his beard, and likely wore a brown wig to cover his bald pate. The small group stalled at the Potomac, which abnormally foul weather had caused to partially freeze. Attempting to cross it could result in getting trapped by the ice, at which point a patrolling Union gunboat would find them an easy target. They waited three days before making their first attempt, and this failed. The next endeavor succeeded, although the weather had not improved.

The three made their way to a plantation house on the outskirts of Washington, D.C., owned by a family of Southern sympathizers. How Kenner and his companions got there remains debatable as two contradicting accounts exist. At this point either one of Kenner’s Secret Service companions procured horses, or the three men trudged through high snow drifts on foot until they reached their goal. The family living there drove the Kenner party to a nearby village in which Kenner spent $80 in gold for an old carriage and a few horses. At or around this moment he sent Merrick home.

He and his remaining companion headed to still another house of Southern sympathizers. Here Howell instructed Kenner to turn over all his money and papers to a young lady living within. Kenner reluctantly did so. The next morning Howell, who had quartered elsewhere, explained the reason for this. The young woman had placed all of Kenner’s articles upon her person as a means of keeping them safe. If Union officials came and searched the house and its occupants—something that occurred here from time to time—they would never intimately examine a young lady. She gave Kenner his possessions back.

He and Howell next headed to the Surratt house (from which members of this family had become involved with a plot to kidnap and then assassinate President Lincoln), only to find the Surratts had moved away. Kenner and Howell had no choice but to stay overnight in the woods. The next day they caught a train to Baltimore. On board they sat far apart, one planning to deny knowing the other if captured. The two rode in a non-smoking car since mainly rural folk used it, reducing the chances of anyone recognizing Kenner. In Baltimore, Kenner had an hour wait until boarding a train for Philadelphia. He passed the time shopping, buying and dressing in garb that made him look like a Pennsylvanian farmer. At this point Howell left for home, believing his cohort now planned to head straight for Canada.

Kenner arrived in New York City without incident. He took a room at the Metropolitan Hotel, an establishment he did not like because he feared the black waiters working there might recognize him (demonstrating his notoriety as a slave master). When he learned that Henry Stuart Foote, a former senator from Mississippi who had fled north at the outbreak of the war, lived in the hotel, he retreated to his room to avoid being recognized. He wrote a vague note to D.M. Hildreth, an old friend and the co-owner of the New York Hotel. He stated he had something to give Hildreth, but he could only do so in person. Would Hildreth please come see him? He signed the note as “A.B. Kinglake,” telling Hildreth that while he might not recognize the name, he would know the person.

When Hildreth arrived and saw from whom the mysterious note had come, he exclaimed, “Great God Kenner, where are you from? How did you get here and where are you going? Don’t you know your life is in danger?” Kenner said he put his fate in Hildreth’s hands. Hildreth asked Kenner what he wanted. He needed a room at the New York Hotel, and a ticket on a steamer to take him to England. Kenner told him he had business interests to attend there. Hildreth obtained a ticket using Kenner’s nom de guerre, A.B. Kinglake, for a cabin aboard the America, a steamer of the Bremen line bound for Southampton that would sail on February 11, 1865. Hildreth procured an old steam trunk covered with a variety foreign stamps from abroad to give Kenner the look of one who frequently traveled overseas.

When Kenner reached the America’s gangplank on the day of her departure, he found Federals guarding it. One took an unnatural interest in him. Thinking quickly, he bought a newspaper and casually read it. He sat by some other waiting passengers and spoke with them in French. The guard lost interest. He boarded the ship without further incident.

When he saw Union officials sailing as well, he decided it best to keep to himself. He quietly suffered insults upon the Confederacy made by pro-Union Americans. Years later he claimed that shortly after disembarking, he confronted these defamers of the Southern cause in a local restaurant. There he warned, “I am a confederate [sic] and have had to listen to your abuse during the voyage over, but I want you to understand that if I hear another word of it I will cut your throats.” Considering the need for secrecy and the fact that making death threats would hardly help his diplomatic mission, it seems likely that his recollection of this altercation came not from memory but wishful thinking.

He made his way to London to find Slidell and Mason, the latter of whom had gone to France. He and Slidell headed to Paris to see him. At their first meeting, which included an American banker named William Wilson Corcoran, Kenner gave his compatriots their instructions. Mason balked at the proposed plan, but upon realizing the extent of the powers given to him by Davis and Benjamin, he submitted to Kenner’s authority.

Slidell arranged for Kenner to meet with France’s minister of foreign affairs, who refused to commit to anything. He said that France would only aid the Confederate government if Britain agreed to do so as well. A few weeks later Slidell met with France’s iron-fisted monarch, Emperor Louis Napoleon, who took the same position as his foreign minister: only if Britain committed would he. He claimed the emancipation of slaves in the South did not nor had it ever influenced his policy on the matter. The French posture convinced Kenner of the futility of setting up an American-Franco bank in the country, which he did not pursue.

He and Mason returned to England on March 13. There Mason requested an interview with Lord Henry John Palmerston, the British prime minister. He received one the next day. At this meeting the last hope for the Confederacy’s survival died. Palmerston bluntly stated that Britain’s failure to recognize the Confederacy never had a thing to do with slavery, and it would not change. One of Mason’s friends in the British government, the Earl of Donoughmore, later claimed that the Confederacy’s embracement of slavery had indeed prevented the British government from officially recognizing it, or of breaking the Union’s blockade.

Emperor Napoleon chose not to support the South because he feared war with the United States. While he reckoned France could match America militarily, he had concerns that the French people would not support such a conflict. He further worried his European enemies might use it as an excuse for aggression against his country.

The British had their own reasons for avoiding a war with the United States, and this, too, did not involve concern over America’s military might—British observers generally did not have a high opinion of either the Union or Confederate armies. Before the American Civil War erupted, the price of cotton had plummeted because of overproduction. The war caused a cotton drought, forcing its price up and thus significantly raising the value of British-produced textiles. Profit more than anything else, then, had prompted the British government to avoid recognition of the Confederacy, although other factors such the morality of supporting a slave state (as stated by the Earl of Donoughmore) as well as Britain’s dependence on American Northern wheat certainly contributed to this decision.🕜

When Kenner reached the America’s gangplank on the day of her departure, he found Federals guarding it. One took an unnatural interest in him. Thinking quickly, he bought a newspaper and casually read it. He sat by some other waiting passengers and spoke with them in French. The guard lost interest. He boarded the ship without further incident.

When he saw Union officials sailing as well, he decided it best to keep to himself. He quietly suffered insults upon the Confederacy made by pro-Union Americans. Years later he claimed that shortly after disembarking, he confronted these defamers of the Southern cause in a local restaurant. There he warned, “I am a confederate [sic] and have had to listen to your abuse during the voyage over, but I want you to understand that if I hear another word of it I will cut your throats.” Considering the need for secrecy and the fact that making death threats would hardly help his diplomatic mission, it seems likely that his recollection of this altercation came not from memory but wishful thinking.

He made his way to London to find Slidell and Mason, the latter of whom had gone to France. He and Slidell headed to Paris to see him. At their first meeting, which included an American banker named William Wilson Corcoran, Kenner gave his compatriots their instructions. Mason balked at the proposed plan, but upon realizing the extent of the powers given to him by Davis and Benjamin, he submitted to Kenner’s authority.

Slidell arranged for Kenner to meet with France’s minister of foreign affairs, who refused to commit to anything. He said that France would only aid the Confederate government if Britain agreed to do so as well. A few weeks later Slidell met with France’s iron-fisted monarch, Emperor Louis Napoleon, who took the same position as his foreign minister: only if Britain committed would he. He claimed the emancipation of slaves in the South did not nor had it ever influenced his policy on the matter. The French posture convinced Kenner of the futility of setting up an American-Franco bank in the country, which he did not pursue.

He and Mason returned to England on March 13. There Mason requested an interview with Lord Henry John Palmerston, the British prime minister. He received one the next day. At this meeting the last hope for the Confederacy’s survival died. Palmerston bluntly stated that Britain’s failure to recognize the Confederacy never had a thing to do with slavery, and it would not change. One of Mason’s friends in the British government, the Earl of Donoughmore, later claimed that the Confederacy’s embracement of slavery had indeed prevented the British government from officially recognizing it, or of breaking the Union’s blockade.

Emperor Napoleon chose not to support the South because he feared war with the United States. While he reckoned France could match America militarily, he had concerns that the French people would not support such a conflict. He further worried his European enemies might use it as an excuse for aggression against his country.

The British had their own reasons for avoiding a war with the United States, and this, too, did not involve concern over America’s military might—British observers generally did not have a high opinion of either the Union or Confederate armies. Before the American Civil War erupted, the price of cotton had plummeted because of overproduction. The war caused a cotton drought, forcing its price up and thus significantly raising the value of British-produced textiles. Profit more than anything else, then, had prompted the British government to avoid recognition of the Confederacy, although other factors such the morality of supporting a slave state (as stated by the Earl of Donoughmore) as well as Britain’s dependence on American Northern wheat certainly contributed to this decision.🕜