Northern Ohio Railway Museum

The Northern Ohio Railway Museum is heaven for trolley enthusiasts. There is only one problem for the trolley (a name interchangeable with streetcar) layman such as myself. Lovers of trolleys tend to be more interested in the technical details of these artifacts of mass movement rather than how they how they affected and shaped of the lives of those who used them. This is the focus the Northern Ohio Railway Museum takes, as exemplified by one of its information signs:

Fortunately the museum’s extensive number of information signs written for enthusiasts of the cars themselves were supplemented by my excellent tour guide, Mark Adamic, who graciously and enthusiastically answered all the questions I asked. I thought, for example, that the only streetcars still in use in America were in San Francisco, but I was told this is not the case. Off the top of his head, he named a dozen or so American cities from coast to coast where streetcars can be found as well as a few that were planning on introducing them. According to railwaypreservation.com, there are, as of January 2020, thirty-one U.S. cities with running streetcar systems, seven under construction, and an impressive sixty either planned or proposed.

The first streetcar ever put into service appeared in Richmond, Virginia, in 1888. Built by Frank J. Sprague, it ran over a twelve mile stretch of track and proved that an electric trolley system could and did work, sparking a boom in the creation of streetcar systems. Sprague graduated from the Naval Academy in Annapolis, and after leaving the navy, invented a non-spark electric motor that could be used on an industrial scale. For a brief time he worked for Thomas Edison, but like many of the gifted people who worked for that man, the relationship quickly soured. After parting ways, Sprague founded his own company to produce an electric motor bearing his name. His greatest contribution to the electric railroad was the invention of the multi-unit system of train control that could either be a master or slave to a control in another car. He introduced this on Chicago’s elevated railroad.

Competition with steam railroads often resulting in fare wars and other conflicts. In 1906, California’s Northern Electric Railway and the steam-powered Western Pacific were building competing roads towards Sacramento with the two sharing tracks near Pleasant Grove in Sutter County plus a bridge that crossed the American River. In June 1906 Western Pacific decided to assert its land usage rights by taking possession of the Bee Farm in Marysville along the Yuba River. Knowing it had a dubious claim, the company sent its workers put down the tracks on the sly.

At one o’clock in the morning on January 13, 1907, a work crew of about 100 Northern Electric men rushed onto the Bee Farm from all directions. The single watchman put there by Western Pacific could do nothing. The Northern Electric crew ripped up Western Electric’s tracks and began replacing them with its own. The watchman, when released, went into Marysville to inform his employers what had happened. A company attorney immediately began the process of procuring a restraining order.

The first streetcar ever put into service appeared in Richmond, Virginia, in 1888. Built by Frank J. Sprague, it ran over a twelve mile stretch of track and proved that an electric trolley system could and did work, sparking a boom in the creation of streetcar systems. Sprague graduated from the Naval Academy in Annapolis, and after leaving the navy, invented a non-spark electric motor that could be used on an industrial scale. For a brief time he worked for Thomas Edison, but like many of the gifted people who worked for that man, the relationship quickly soured. After parting ways, Sprague founded his own company to produce an electric motor bearing his name. His greatest contribution to the electric railroad was the invention of the multi-unit system of train control that could either be a master or slave to a control in another car. He introduced this on Chicago’s elevated railroad.

Competition with steam railroads often resulting in fare wars and other conflicts. In 1906, California’s Northern Electric Railway and the steam-powered Western Pacific were building competing roads towards Sacramento with the two sharing tracks near Pleasant Grove in Sutter County plus a bridge that crossed the American River. In June 1906 Western Pacific decided to assert its land usage rights by taking possession of the Bee Farm in Marysville along the Yuba River. Knowing it had a dubious claim, the company sent its workers put down the tracks on the sly.

At one o’clock in the morning on January 13, 1907, a work crew of about 100 Northern Electric men rushed onto the Bee Farm from all directions. The single watchman put there by Western Pacific could do nothing. The Northern Electric crew ripped up Western Electric’s tracks and began replacing them with its own. The watchman, when released, went into Marysville to inform his employers what had happened. A company attorney immediately began the process of procuring a restraining order.

As an advocate of mass transit, I would like nothing more than to see a return to an electric-based rail system to reduce the use of automobiles. I happen to live smack in the middle of what was once the largest interurban electric rail systems in the United States, the Lake Shore Electric Railway Company (LSE). Not that you would know it. Virtually none of its infrastructure exists today. Were it resurrected, I would happily use it instead of my car for trips to Toledo or Cleveland, its terminal points.

My first encounter with the LSE was during a childhood adventure. Behind my friends’ property down the street were two sets of railroad tracks, one of the south side of Bellevue Reservoir Number One, the other to its north. A couple times my friends and I walked down both sets of tracks to find a “pyramid.” In my child’s mind I thought they had been built by some lost civilization. It wasn’t until years later that I realized it is likely they were pillars for a long gone trolley bridge that probably belonged to the LSE.

After its demise, my grandmother eventually had to learn to drive, but she wasn’t very good at it. Near the end of her driving career, she was notorious for crashing into cars in parking lots, then taking off without reporting the accident. Admitting this now will result in no legal jeopardy. My grandmother passed away in 2005 and any criminal charges or liability are long past the statue of limitations. There is a more detailed account of the LSE’s history in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Medina County.

I’ve never ridden in a trolley, and although museum offers this opportunity, I declined to do so during my visit because all it did was travel back and forth a few hundred yards on a straight track. In years to come this will change. The museum plans to expand the track to encircle its grounds, offering a somewhat more robust ride. According to the museum’s January–February 2019 newsletter the Northern Light, this expansion is expensive and technically difficult. The museum had to, for example, purchase a costly isolation transformer to reduce the power going to the DC rectifier, which converts the incoming AC current to DC that streetcars run on.🕜

My first encounter with the LSE was during a childhood adventure. Behind my friends’ property down the street were two sets of railroad tracks, one of the south side of Bellevue Reservoir Number One, the other to its north. A couple times my friends and I walked down both sets of tracks to find a “pyramid.” In my child’s mind I thought they had been built by some lost civilization. It wasn’t until years later that I realized it is likely they were pillars for a long gone trolley bridge that probably belonged to the LSE.

After its demise, my grandmother eventually had to learn to drive, but she wasn’t very good at it. Near the end of her driving career, she was notorious for crashing into cars in parking lots, then taking off without reporting the accident. Admitting this now will result in no legal jeopardy. My grandmother passed away in 2005 and any criminal charges or liability are long past the statue of limitations. There is a more detailed account of the LSE’s history in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Medina County.

I’ve never ridden in a trolley, and although museum offers this opportunity, I declined to do so during my visit because all it did was travel back and forth a few hundred yards on a straight track. In years to come this will change. The museum plans to expand the track to encircle its grounds, offering a somewhat more robust ride. According to the museum’s January–February 2019 newsletter the Northern Light, this expansion is expensive and technically difficult. The museum had to, for example, purchase a costly isolation transformer to reduce the power going to the DC rectifier, which converts the incoming AC current to DC that streetcars run on.🕜

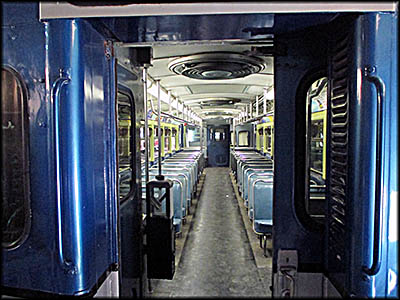

Lake Shore Electric coach 151 belonged to a group of innovative cars. This group had multi-unit equipment that allowed one motorman to control the operation of all cars in a train. This technology made 151 and her sisters the first LSE cars that could run in multi-car trains. This multi-unit technology is used today on the Rapid Transit. On Saturday, May 14, 1938, car 151 was the last wooden interurban to leave Cleveland. After abandonment of the line, the car body was used as a workshop in Norwalk, Ohio[,] until the mid-1990’s. Then it went to the Grand Rapids Electric Railway Museum before coming here.