Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum

Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum

USS Laffey

Laffey’s Command Center (Radar and Sonar)

Laffey’s Bridge

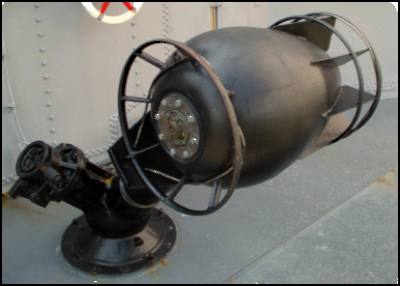

This is a Mark 9 depth charge on the Laffey. It doesn’t look much like the cannisters you see in the movies.

USS Yorktown

As much as I love nautical history and have made it a point to tour any and all marine vessels that I come across, I’d never managed to step foot on an aircraft carrier. Nor, for that matter, had I ever been on a destroyer. And so at Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum I was finally able to visit both plus far more than I’d ever expected. In addition to the destroyer USS Laffey, the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown, and the diesel-powered submarine USS Clamagore, there is also the Medal of Honor Museum on the Yorktown’s hanger deck and the Vietnam Experience near the museum’s entrance.

Touring this museum is not for the faint of heart. If you want to see everything, plan on taking six to eight hours. I went everywhere I could and even by skipping most of the various videos scattered about, it still took me about six hours. If you have any health problems, especially those affected by climbing up and down ladders and stairs, or you have a fear of enclosed places, this is not the museum for you. Also, if you don’t like heat, go during the fall or winter. It was in the upper 90s the day I went with a heat index of 105 degrees, and the majority of what you tour is not air conditioned.

Touring this museum is not for the faint of heart. If you want to see everything, plan on taking six to eight hours. I went everywhere I could and even by skipping most of the various videos scattered about, it still took me about six hours. If you have any health problems, especially those affected by climbing up and down ladders and stairs, or you have a fear of enclosed places, this is not the museum for you. Also, if you don’t like heat, go during the fall or winter. It was in the upper 90s the day I went with a heat index of 105 degrees, and the majority of what you tour is not air conditioned.

My three traveling companions and I started our tour on the Laffey, which was commissioned on February 8, 1944, in honor of the previous destroyer that bore that name that had sunk on November 13, 1942, during the Battle of Guadalcanal. The name Laffey was in honor of Seaman Bartlett Laffey, who earned the Medal of Honor during the Civil War. After her shakedown cruise, the replacement Laffey escorted a shipping convoy to England, then stuck around to support the D-Day invasion. In July she headed back to the mainland United States where she was given a brief overhaul.

From there she sailed to the Pacific, arriving at Pearl Harbor on September 18, 1944, at which she received a dazzle paint scheme designed to make it harder for submarines to get an accurate range on her. (An aside: I’ve never seen a World War II movie with ships using this form of camouflage, and if anyone knows of one, please let me know.) On April 16, 1945, while serving on radar picket duty off Okinawa, the Laffey showed her stuff. A massive twenty-two Japanese bombers and kamikazes attacked her that day, and of those, three bombs and five kamikazes hit her, killing thirty-two and wounding seventy-one crewmen. Despite the damage, she stayed afloat and became known as “the ship that would not die.” Repaired, she returned to active service until being put into reserve in 1947. Brought back for the Korean War, she stayed in active service until her final decommission in 1975.

From there she sailed to the Pacific, arriving at Pearl Harbor on September 18, 1944, at which she received a dazzle paint scheme designed to make it harder for submarines to get an accurate range on her. (An aside: I’ve never seen a World War II movie with ships using this form of camouflage, and if anyone knows of one, please let me know.) On April 16, 1945, while serving on radar picket duty off Okinawa, the Laffey showed her stuff. A massive twenty-two Japanese bombers and kamikazes attacked her that day, and of those, three bombs and five kamikazes hit her, killing thirty-two and wounding seventy-one crewmen. Despite the damage, she stayed afloat and became known as “the ship that would not die.” Repaired, she returned to active service until being put into reserve in 1947. Brought back for the Korean War, she stayed in active service until her final decommission in 1975.

The Laffey had two rotating 5-inch duel turret guns—one fore and one aft—that fired 38 caliber rounds. It was into the aft gun that my traveling companions entered right after boarding. Within we experienced an interactive simulation of the aforementioned kamikaze attack that included video, crew voices, sound effects, and shaking to give us an idea of what Okinawa was like. Sadly, the turret was hit during that battle and several members of the gun’s crew died.

What made this anti-aircraft gun particularly effective was something no other nation at the time had: computer-assisted aiming. This came from the Mark I built by the Ford Instrument Company. When installed in 1944, this analog computer cost $75,000. It resided in control room below deck that had three stations, one for elevation, one for bearing, and one for range. It was with the assistance of this machine that the Laffey shot down almost half the aircraft that attacked her at Okinawa.

With most of the destroyer open to the public, it doesn’t take long to appreciate just how dexterous the crew had to be to negotiate the ship’s cramped ladders, especially during a rough sea or while under attack. One information sign noted that before the Laffey’s class of destroyer—the Allen Sumner—was introduced, sailors on American destroyers going fore to aft could not get from one end to the other without having to go outside at some point, which, during rough seas, sometimes resulted in men being washed overboard while going to their duty stations.

What made this anti-aircraft gun particularly effective was something no other nation at the time had: computer-assisted aiming. This came from the Mark I built by the Ford Instrument Company. When installed in 1944, this analog computer cost $75,000. It resided in control room below deck that had three stations, one for elevation, one for bearing, and one for range. It was with the assistance of this machine that the Laffey shot down almost half the aircraft that attacked her at Okinawa.

With most of the destroyer open to the public, it doesn’t take long to appreciate just how dexterous the crew had to be to negotiate the ship’s cramped ladders, especially during a rough sea or while under attack. One information sign noted that before the Laffey’s class of destroyer—the Allen Sumner—was introduced, sailors on American destroyers going fore to aft could not get from one end to the other without having to go outside at some point, which, during rough seas, sometimes resulted in men being washed overboard while going to their duty stations.

On both the Laffey and Yorktown, there are a number of interactive computer interfaces. One in the Laffey’s engine room contains videos, and one in the Yorktown tells you how the engine system worked. There are a couple places where a simulated person shows up a screen. On the Yorktown, for example, there is a seaman working in the engine room. On the Laffey there an is one in the radar/sonar control room one that asks you to sit down or otherwise stay in place while a tense Cold War scenario with the potential to start World War III plays out.

The Yorktown’s entrance took us into her hanger, which has been modified to accommodate a visitor’s help desk, a snack bar, a movie theater, and the Medal of Honor Museum (more on that later). Also on the hanger deck is a replica of the Apollo 8 capsule into which you can enter to get a taste of that crew’s experience. Because a nearby information sign gave details about the tragic fire of Apollo 1 that killed Virgil "Gus" Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee on January 27, 1967, I thought this exhibit was a simulation of that fire! I was so horrified by such a ghoulish thing I berated one of my traveling companions for standing in line to get into it. (In the end he gave up waiting because the line was too long.)

During the bombing of Pearl Harbor no American aircraft carriers were lost because they were out to sea. While this kept the U.S. Navy from being completely crippled in the Pacific, things did not go all that well for this arm of the U.S. military in the first six months after Pearl Harbor. But thanks to an intelligence coup, the Navy laid a successfully trap for the Japanese at Midway Island. On the battle’s opening day, June 4, 1942, the American aircraft carrier Yorktown was hit by two torpedoes and sank. In her honor, an Essex-class aircraft carrier then under construction, the Bon Homme Richard, was renamed Yorktown. During her launch, she started sliding down the slip prematurely as if eager to get on with her mission. Eleanor Roosevelt smacked her with a champagne bottle, but it bounced off. She caught it and tried again, this time with success.

The Yorktown’s first captain, Joseph “Jocko” Clark, was a hard taskmaster, as this quotation from an information sign demonstrates: “If you can’t run, walk. If you can’t walk, crawl. But get the job done. If you can’t get the job done, get off my ship!” (I suspect his language was a bit more salty than this; it is no myth that seamen like to swear profusely.) The strong-willed Captain Clark was one of the most effective commanders in the Pacific because he was aggressive and did not hesitate to make split second decisions. It was men like him who won the naval war in the Pacific.

The Yorktown’s entrance took us into her hanger, which has been modified to accommodate a visitor’s help desk, a snack bar, a movie theater, and the Medal of Honor Museum (more on that later). Also on the hanger deck is a replica of the Apollo 8 capsule into which you can enter to get a taste of that crew’s experience. Because a nearby information sign gave details about the tragic fire of Apollo 1 that killed Virgil "Gus" Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee on January 27, 1967, I thought this exhibit was a simulation of that fire! I was so horrified by such a ghoulish thing I berated one of my traveling companions for standing in line to get into it. (In the end he gave up waiting because the line was too long.)

During the bombing of Pearl Harbor no American aircraft carriers were lost because they were out to sea. While this kept the U.S. Navy from being completely crippled in the Pacific, things did not go all that well for this arm of the U.S. military in the first six months after Pearl Harbor. But thanks to an intelligence coup, the Navy laid a successfully trap for the Japanese at Midway Island. On the battle’s opening day, June 4, 1942, the American aircraft carrier Yorktown was hit by two torpedoes and sank. In her honor, an Essex-class aircraft carrier then under construction, the Bon Homme Richard, was renamed Yorktown. During her launch, she started sliding down the slip prematurely as if eager to get on with her mission. Eleanor Roosevelt smacked her with a champagne bottle, but it bounced off. She caught it and tried again, this time with success.

The Yorktown’s first captain, Joseph “Jocko” Clark, was a hard taskmaster, as this quotation from an information sign demonstrates: “If you can’t run, walk. If you can’t walk, crawl. But get the job done. If you can’t get the job done, get off my ship!” (I suspect his language was a bit more salty than this; it is no myth that seamen like to swear profusely.) The strong-willed Captain Clark was one of the most effective commanders in the Pacific because he was aggressive and did not hesitate to make split second decisions. It was men like him who won the naval war in the Pacific.

The Yorktown had a crew of over 3,500, and feeding, housing, laundering for so many was something that needed to be done on an industrial scale. The galley, for example, operated twenty-four hours a day, seven days of week. Meals were served four times a day, and while at sea, soup was always available. The galley’s companion, the bakery a lot of food as well. Take chocolate chip cookies: a recipe for 10,000 of these tasty treats required, among other ingredients, 112 pounds of chocolate chips. 500 eggs, 100 pounds of white sugar, 75 pounds of brown sugar, and 12 pounds of butter.

Back on the hanger deck, I went into the blessedly air conditioned Medal of Honor Museum. Introduced in 1861, according to the museum’s information sign, it is awarded “by the President, in the name of Congress, to a person who, while a member of the Armed Forces, distinguishes himself or herself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his or her life above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in action against an enemy of the United States.” There are more criteria, but that gives the gist of what one needs to do to earn one.

The medal’s youngest recipient ever was William Johnson, who earned it at the age of eleven for being the only drummer to return from the Seven Days Battles (part of General George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign) with his instrument still in hand. All the other drummers had tossed theirs during a retreat. It was President Abraham Lincoln who recommended Johnson receive the Medal of Honor for his bravery.

Some who have earned one of these have had naval vessels named after them. One such person was Major General Smedley D. Butler of the Marines Corp. He won the medal twice, but here is an interesting twist. He thought little of this and other medals and ribbons, so when he received a Medal of Honor for his part in an attack on Vera Cruz in 1914, he returned it, saying he didn’t feel he’d done anything to deserve it. The Navy gave it back and ordered him to wear it.

Back on the hanger deck, I went into the blessedly air conditioned Medal of Honor Museum. Introduced in 1861, according to the museum’s information sign, it is awarded “by the President, in the name of Congress, to a person who, while a member of the Armed Forces, distinguishes himself or herself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his or her life above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in action against an enemy of the United States.” There are more criteria, but that gives the gist of what one needs to do to earn one.

The medal’s youngest recipient ever was William Johnson, who earned it at the age of eleven for being the only drummer to return from the Seven Days Battles (part of General George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign) with his instrument still in hand. All the other drummers had tossed theirs during a retreat. It was President Abraham Lincoln who recommended Johnson receive the Medal of Honor for his bravery.

Some who have earned one of these have had naval vessels named after them. One such person was Major General Smedley D. Butler of the Marines Corp. He won the medal twice, but here is an interesting twist. He thought little of this and other medals and ribbons, so when he received a Medal of Honor for his part in an attack on Vera Cruz in 1914, he returned it, saying he didn’t feel he’d done anything to deserve it. The Navy gave it back and ordered him to wear it.

After finishing the tour of the Yorktown, two of my traveling companion retired to picnic tables. My remaining traveling companion and I headed to the Clamagore, a diesel-electric submarine commissioned on June 28, 1945. She is not in good shape. Some of her deck plating has been stripped off and rust is decaying her hull. Although I didn’t know it at the time, it turns out Patriots Point intends to sink her off shore as an artificial reef. However, the USS Clamagore SS-343 Restoration and Maintenance Association has sued to prevent this, and considering the speed of U.S. courts in civil matters such as this, it might be years before it is resolved.

Put into service too late to fight in World War II, the Clamagore became a Cold War asset for the United States. Just four years after being launched, she was refitted with a faster propulsion system, the GUPPY II (Greater Underwater Propulsion Power). In May 1962 she was updated once more to the GUPPY III system. During its installation, she was cut in two and, according to an information sign, “a 15 foot, 55 ton section containing a modern SONAR room … was added.” When decommissioned in 1975, she was one of the last diesel-electric subs in service. She arrived at Patriots Point in 1981 and is the only GUPPY III submarine still in tact in the United States. In 1989 she was made an historic landmark, although this does not seem to deter Patriots Point from making her into a reef.

By the time I got to the Vietnam Experience, I had exhausted my supply of traveling companions, so into this I went alone. It is set up to look like an army base in South Vietnam and is accompanied by a number of loud sound effects, including gunfire, in an effort to reproduce this experience. A sign at the entrance warns those sensitive to loud sounds not to enter, but fails to tell military combat veterans not to go in if they are prone to flashbacks or PTSD.

From the entrance it appears quite small. I headed to the closest building in sight, a structure made of corrugated metal shaped like a cylinder cut in half. Inside it is partly designed to look like part of a block in what I presume is Saigon, but whoever made this did a poor job of it. This building nonetheless contains a treasure trove of artifacts and information signs. An example of the former is a Vespa scooter, which was made by the Italian company Piaggo. During their rule of Indochina, the French brought many of these, so by the time the Americans arrived, they were everywhere.

Put into service too late to fight in World War II, the Clamagore became a Cold War asset for the United States. Just four years after being launched, she was refitted with a faster propulsion system, the GUPPY II (Greater Underwater Propulsion Power). In May 1962 she was updated once more to the GUPPY III system. During its installation, she was cut in two and, according to an information sign, “a 15 foot, 55 ton section containing a modern SONAR room … was added.” When decommissioned in 1975, she was one of the last diesel-electric subs in service. She arrived at Patriots Point in 1981 and is the only GUPPY III submarine still in tact in the United States. In 1989 she was made an historic landmark, although this does not seem to deter Patriots Point from making her into a reef.

By the time I got to the Vietnam Experience, I had exhausted my supply of traveling companions, so into this I went alone. It is set up to look like an army base in South Vietnam and is accompanied by a number of loud sound effects, including gunfire, in an effort to reproduce this experience. A sign at the entrance warns those sensitive to loud sounds not to enter, but fails to tell military combat veterans not to go in if they are prone to flashbacks or PTSD.

From the entrance it appears quite small. I headed to the closest building in sight, a structure made of corrugated metal shaped like a cylinder cut in half. Inside it is partly designed to look like part of a block in what I presume is Saigon, but whoever made this did a poor job of it. This building nonetheless contains a treasure trove of artifacts and information signs. An example of the former is a Vespa scooter, which was made by the Italian company Piaggo. During their rule of Indochina, the French brought many of these, so by the time the Americans arrived, they were everywhere.

It was when I exited this building through the far door that I realized just how large an area the Vietnam Experience covered. Here I saw more buildings than I’d initially guessed were there as well as helicopters and other equipment of war. And just when I thought I was done, I went through a tunnel that took me into another good sized area in which there was another building, a helicopter, a tank, and a destroyed flipped over jeep.

An information sign told me this was a replica of Khe Sanh, an American base “in the northwest mountains of South Vietnam … [that was] just south of the border of North Vietnam and west of the border with Laos. This key piece of terrain controlled access to roads, trails, and rivers in the area.” In the fall of 1967 the North Vietnam Army (NVA) started massing nearby, bringing in an estimated 22,000 to 28,000 men. The NVA attacked the base on January 21, 1968—the Tet Offensive would began just days later on the 31st—but the Marines manning this base kept them at bay. Ariel support arrived and dropped an estimated 100,000 tons of ordnance on the NVA. Although the NVA failed to take the base, over the next few months the Americans dismantled and abandoned it for fear the NVA would attack again.

I thought I’d just rush through the Vietnam Experience because it had been a long visit already, but, save for the cheesy street scene, it was so well done and informative that I took my time. Never before had I stepped foot in a replica Vietnam base, so that in and of itself was a new experience. Unless you have a compelling reason not to, I suggest you make it a point to tour this. It might not be a bad idea to do so before visiting the ships because at this point you’ll not have worn yourself out climbing a mass of ladders and stairs.🕜

An information sign told me this was a replica of Khe Sanh, an American base “in the northwest mountains of South Vietnam … [that was] just south of the border of North Vietnam and west of the border with Laos. This key piece of terrain controlled access to roads, trails, and rivers in the area.” In the fall of 1967 the North Vietnam Army (NVA) started massing nearby, bringing in an estimated 22,000 to 28,000 men. The NVA attacked the base on January 21, 1968—the Tet Offensive would began just days later on the 31st—but the Marines manning this base kept them at bay. Ariel support arrived and dropped an estimated 100,000 tons of ordnance on the NVA. Although the NVA failed to take the base, over the next few months the Americans dismantled and abandoned it for fear the NVA would attack again.

I thought I’d just rush through the Vietnam Experience because it had been a long visit already, but, save for the cheesy street scene, it was so well done and informative that I took my time. Never before had I stepped foot in a replica Vietnam base, so that in and of itself was a new experience. Unless you have a compelling reason not to, I suggest you make it a point to tour this. It might not be a bad idea to do so before visiting the ships because at this point you’ll not have worn yourself out climbing a mass of ladders and stairs.🕜

On the Yorktown’s Flight Deck

Officers’ Briefing Room on the Yorktown

Yorktown’s Galley

Yorktown’s Hanger

Hellcat in the Yorktown’s Hanger

USS Clamagore

Inside the Clamagore

The Vietnam Experience