SOUVENIR HUNTING

Copyright © 2014 by Mark Strecker.

AN AMERICAN TRADITION

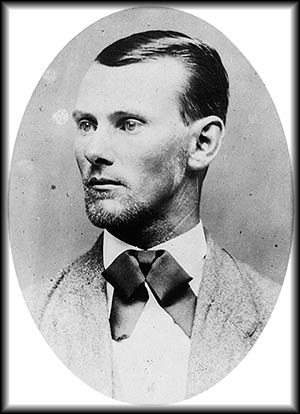

Jesse James

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

House of Jesse James

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Landau Carriage

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

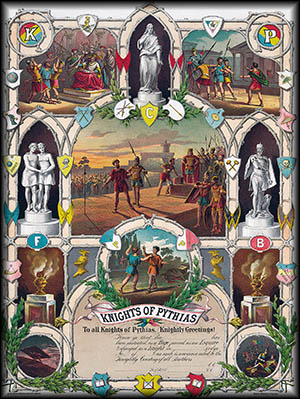

Knights of Pythias

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

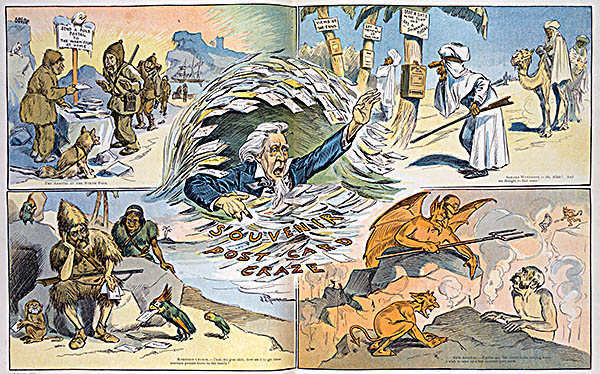

This cartoon pokes fun at the American obsession with souvenir postcards.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Visit any tourist destination in America and you will inevitably come across a gift shop selling souvenirs, most often in the form of mugs, t-shirts, and cheap toys that will amuse your children for ten minutes and break in twelve. The desire to acquire keepsakes from places visited or events attended has often motivated Americans to travel vast distances to acquire them, especially when it involved the infamous.

Those who made acquisitions such as these often marked them with notes or wrote directly on them so future generations would know their provenance. Thomas Jefferson did this when he sent the portable desk upon which he wrote the Declaration of Independence to his niece as a wedding present. With it he included a note explaining its significance, adding he felt this piece of Revolutionary history might in the future serve as a relic of the United States akin to the sort kept for saints.

Souvenir hunters haven’t always filled out their collections in the most ethical of ways. Plymouth Rock, which had no protection from the public until 1859, has lost about one-third of its original size thanks to visitors chipping off pieces they took home as mementos, a practice encouraged by the fact a hammer set on site for those who forgot their own. At large public gathering guests often wandered off with the tableware. At a January 1908 assembly of prominent citizens hosted by a Knights of Pythias lodge in Abingdom, Illinois, thirty-three of the eighty-four borrowed souvenir spoons used for the occasion disappeared.

Appropriating objects found at a place or event of significance remained a habit of Americans well into the twentieth century. In the summer of 1922 Maurice Barres of the Chamber of Deputies of the French Academy asked American veterans of the recent Great War who had made off with pieces from the Cathedral of Nôtre Dame de Reims to please return them. This church, in which many events of significance in French history occurred, first suffered damage from German shelling on September 4, 1914. On September 19 of that same year, another attack started a fire that destroyed the entire structure, melting its roof and bells—about 400 tons of lead and metal. It would take thirteen years and a lot of American money to rebuild it.

Souvenir hunters haven’t always filled out their collections in the most ethical of ways. Plymouth Rock, which had no protection from the public until 1859, has lost about one-third of its original size thanks to visitors chipping off pieces they took home as mementos, a practice encouraged by the fact a hammer set on site for those who forgot their own. At large public gathering guests often wandered off with the tableware. At a January 1908 assembly of prominent citizens hosted by a Knights of Pythias lodge in Abingdom, Illinois, thirty-three of the eighty-four borrowed souvenir spoons used for the occasion disappeared.

Appropriating objects found at a place or event of significance remained a habit of Americans well into the twentieth century. In the summer of 1922 Maurice Barres of the Chamber of Deputies of the French Academy asked American veterans of the recent Great War who had made off with pieces from the Cathedral of Nôtre Dame de Reims to please return them. This church, in which many events of significance in French history occurred, first suffered damage from German shelling on September 4, 1914. On September 19 of that same year, another attack started a fire that destroyed the entire structure, melting its roof and bells—about 400 tons of lead and metal. It would take thirteen years and a lot of American money to rebuild it.

Take the assassination of Jesse James by Bob Ford on April 3, 1882. Ford shot James in the back as the latter stood upon a chair dusting a picture. Not long after, James’ widow decided to auction off most of the contents of her St. Joseph, Missouri, home in an effort to raise money on which she and her two children could live. People traveled from as far away as New York City to bid these items, and about one thousand attended. The auctioneer stood on a kitchen table outside a window through which the few people in the house handed him articles for sale.

These included a cane-bottom chair (sold for $2.50), a wash boiler (sold for twenty-five cents), Jesses’ black and tan dog (sold for $15), and the straw mattress upon which Jesse slept (sold for $2). The feather duster he held in hand when killed sold for $4, and the chair upon which he stood during this tragic moment for $3.25. A silver-plated revolver given to James a few days before he embarked on the Blue Cut Train Robbery sold at the auction for almost $17. If this came up for bid today, it would likely sell for a great deal more in comparative value to what the original purchaser paid. The last gun known to belong to James sold in 2009 for $230,000. The James sale proved a success. It earned $149.60 (about $3,500 in today’s money) for items normally auctioned off at about $50.

These included a cane-bottom chair (sold for $2.50), a wash boiler (sold for twenty-five cents), Jesses’ black and tan dog (sold for $15), and the straw mattress upon which Jesse slept (sold for $2). The feather duster he held in hand when killed sold for $4, and the chair upon which he stood during this tragic moment for $3.25. A silver-plated revolver given to James a few days before he embarked on the Blue Cut Train Robbery sold at the auction for almost $17. If this came up for bid today, it would likely sell for a great deal more in comparative value to what the original purchaser paid. The last gun known to belong to James sold in 2009 for $230,000. The James sale proved a success. It earned $149.60 (about $3,500 in today’s money) for items normally auctioned off at about $50.

Johnstown: Stone bridge where the debris piled up and where about eighty-eight people burned.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Conemaugh River Dam after its collapse.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Johnstown

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Mount Vernon

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Petty theft such as we have so far seen hardly compared to the ghoulish delight Americans took in snapping up souvenirs in the face of a terrible tragedy, something President Theodore Roosevelt learned firsthand on September 3, 1902. As he and his companions made their way in a horse-drawn Landau carriage from Pittsfield to Lenox, Massachusetts, a trolley hit it, causing the Landau to tip over and spill its passengers onto the ground. Of these, William Craig, Roosevelt’s secret service guard, landed in front of the trolley and suffered a horrible death under its wheels. All others survived; the president came away with nothing more than a few cuts and bruises.

He quickly got back to his feet to see what aid he could give to his companions, taking a moment to bawl out the trolley’s motorman for running his machine so fast. As word of the wreck traveled across the area, souvenir hunters swooped in and started to rip off pieces of the president’s carriage as keepsakes. It took the summoning of the police to stop them from effectively making off with the entire vehicle.

Possibly the most ghoulish incident of this type occurred in the aftermath of a terrible disaster in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The city, at the time containing about 10,000 people, set in a valley of approximately 30,000 people through which flowed the Conemaugh River. Upriver stood the poorly constructed earthen South Fork Dam, a structure that had created and held back Lake Conemaugh, the popular vacation spot where well-known industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon stayed.

A flood caused by a massive twenty-four hour downpour caused the dam to burst on May 31, 1889. For the next thirty-seven to forty-five minutes the lake drained into the valley with a force equal to about that of the Niagara River as it reaches its famous falls. This wall of water swept away all before, leaving nothing but mud behind. A mass of trees, buildings, pieces the dam itself, and even locomotives rode the flood, its destructive force only increasing each time it crashed against bridges and viaducts because it added them to its take.

The flood gathered into a temporary lake along the far side of the valley, then flowed back into it once more, much of the debris coming with it. A stone train bridge in Johnstown that had survived the initial pass of flood water ensnared much of this flotsam, creating a mountain of wreckage higher than the structure itself and trapping perhaps eighty still-living people within. Then it caught fire—possibly helped along by a leaking oil taker train car—and burned nearly all those ensnared within to death. The flood and subsequent fire killed at least 2,200 people. Within a few days authorities declared martial law, placing the adjunct general of Pennsylvania’s national guard, General Daniel Hartman Hastings, in charge.

Soon thousands of outsiders arrived to help, but with them came looters and gawkers, the latter intent on seeing the damage for themselves. The Pennsylvania Railroad, which had a major presence in the valley and had suffered quite a bit of damage from the flood, found its trains overwhelmed by disaster tourists trying to ride into the valley. It appealed to General Hastings to use his men to clear them out of their stations, especially those at Florence and Bolivar. The competing Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) charged tourists $2.35 for a four hour trip into the valley, helpfully reminding them to bring their own lunches because they would have difficulty acquiring food.

These unwanted visitors showed the ugly face of humankind: they sang as they walked through the devastated streets, cracked inappropriate jokes, and climbed over coffins filled with the dead, showing no reverence whatsoever. On Sunday, June 23, they came in the hundreds dressed for vacation, picnic baskets in hand, wandering about without regard for those doing work, taking pictures, asking inane questions, and eating their lunches in abandoned houses.

Many sightseers bought souvenirs from unscrupulous entrepreneurs who had set up booths to sell piece of debris, including broken china, piano keys, buttons, and pieces of shingles. Other visitors pilfered whatever came to hand as they toured. These morbid mementos included the bones of a dead child, a shoe and bandana taken off a corpse not yet buried, and other victims’ photos scattered into the open by the flood. One man even took the sheet covering the corpse of a boy for his keepsake. Local officials soon convinced the B&O to discontinue bringing tourists in, but it took the news of an outbreak of typhoid fever in the area to finally stem the tide of the souvenir hunters.

Although it wouldn’t have helped in the case of President Roosevelt’s wreck or the Johnstown disaster, public attractions started selling their own souvenirs to offer an alternative to petty larceny, and this more than anything else ended the less savory side of collecting souvenirs. President Washington’s Mount Vernon probably qualifies as the first place to do so. Even before it officially opened to tourists after the president’s death, visitors took pieces of the house as souvenirs. In its earliest days the houses’ official caretakers, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union (MVLA), only sold items from its greenhouse, giving third-party vendors the opportunity to sell canes and other items made from wood grown on the estate. Sharing none of their profits with the estate, the MVLA decided to sell its own souvenirs.🕜

He quickly got back to his feet to see what aid he could give to his companions, taking a moment to bawl out the trolley’s motorman for running his machine so fast. As word of the wreck traveled across the area, souvenir hunters swooped in and started to rip off pieces of the president’s carriage as keepsakes. It took the summoning of the police to stop them from effectively making off with the entire vehicle.

Possibly the most ghoulish incident of this type occurred in the aftermath of a terrible disaster in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The city, at the time containing about 10,000 people, set in a valley of approximately 30,000 people through which flowed the Conemaugh River. Upriver stood the poorly constructed earthen South Fork Dam, a structure that had created and held back Lake Conemaugh, the popular vacation spot where well-known industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon stayed.

A flood caused by a massive twenty-four hour downpour caused the dam to burst on May 31, 1889. For the next thirty-seven to forty-five minutes the lake drained into the valley with a force equal to about that of the Niagara River as it reaches its famous falls. This wall of water swept away all before, leaving nothing but mud behind. A mass of trees, buildings, pieces the dam itself, and even locomotives rode the flood, its destructive force only increasing each time it crashed against bridges and viaducts because it added them to its take.

The flood gathered into a temporary lake along the far side of the valley, then flowed back into it once more, much of the debris coming with it. A stone train bridge in Johnstown that had survived the initial pass of flood water ensnared much of this flotsam, creating a mountain of wreckage higher than the structure itself and trapping perhaps eighty still-living people within. Then it caught fire—possibly helped along by a leaking oil taker train car—and burned nearly all those ensnared within to death. The flood and subsequent fire killed at least 2,200 people. Within a few days authorities declared martial law, placing the adjunct general of Pennsylvania’s national guard, General Daniel Hartman Hastings, in charge.

Soon thousands of outsiders arrived to help, but with them came looters and gawkers, the latter intent on seeing the damage for themselves. The Pennsylvania Railroad, which had a major presence in the valley and had suffered quite a bit of damage from the flood, found its trains overwhelmed by disaster tourists trying to ride into the valley. It appealed to General Hastings to use his men to clear them out of their stations, especially those at Florence and Bolivar. The competing Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) charged tourists $2.35 for a four hour trip into the valley, helpfully reminding them to bring their own lunches because they would have difficulty acquiring food.

These unwanted visitors showed the ugly face of humankind: they sang as they walked through the devastated streets, cracked inappropriate jokes, and climbed over coffins filled with the dead, showing no reverence whatsoever. On Sunday, June 23, they came in the hundreds dressed for vacation, picnic baskets in hand, wandering about without regard for those doing work, taking pictures, asking inane questions, and eating their lunches in abandoned houses.

Many sightseers bought souvenirs from unscrupulous entrepreneurs who had set up booths to sell piece of debris, including broken china, piano keys, buttons, and pieces of shingles. Other visitors pilfered whatever came to hand as they toured. These morbid mementos included the bones of a dead child, a shoe and bandana taken off a corpse not yet buried, and other victims’ photos scattered into the open by the flood. One man even took the sheet covering the corpse of a boy for his keepsake. Local officials soon convinced the B&O to discontinue bringing tourists in, but it took the news of an outbreak of typhoid fever in the area to finally stem the tide of the souvenir hunters.

Although it wouldn’t have helped in the case of President Roosevelt’s wreck or the Johnstown disaster, public attractions started selling their own souvenirs to offer an alternative to petty larceny, and this more than anything else ended the less savory side of collecting souvenirs. President Washington’s Mount Vernon probably qualifies as the first place to do so. Even before it officially opened to tourists after the president’s death, visitors took pieces of the house as souvenirs. In its earliest days the houses’ official caretakers, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union (MVLA), only sold items from its greenhouse, giving third-party vendors the opportunity to sell canes and other items made from wood grown on the estate. Sharing none of their profits with the estate, the MVLA decided to sell its own souvenirs.🕜