SunWatch Indian Village / Archeological Park

Museum Entrance

It takes a moment to wrap one’s head around the fact that Ohio’s first inhabitants hunted now long extinct animals such as mastodons, mammoths and giant sloths (leftover bones of which from someone’s meal can be seen at the Firelands Historical Society Museum in Norwalk, Ohio). These earliest people, who archeologists call the not especially creative name Paleo-Indians, also ate natural fruits, nuts and plants, making them hunter-gatherers. As the climate warmed, these Paleo-Indians, who thrived from about 8000 to 1000 b.c., also traded with people from far away places to get items such as marine shells and copper. Sometimes we think of people in what was effectively the stone age as unsophisticated, but just because they had limited technology didn’t mean they lacked the same brainpower and capacity to develop a complex civilization.

The SunWatch Indian Village/Archeological Park from which I gathered the above information wasn’t specific about whether the Paleo-Indians were replaced by those of the next era, the Early Woodland or Adena people, or if their civilization simply evolved into a new phase of sophistication. The Early Woodland People left no written records, so we have no idea what they called themselves. Certainly it wasn’t the Adena. This was the name of a nineteenth century estate owned by Thomas Worthington in Chillicothe on which remnants of this people were found. The Woodland People also traded from places afar and interned their dead in burial mounds. Their era stretches from about 1000 b.c. to 50 c.e. They may have constructed Serpent Mound in Peebles, Ohio.

The SunWatch Indian Village/Archeological Park from which I gathered the above information wasn’t specific about whether the Paleo-Indians were replaced by those of the next era, the Early Woodland or Adena people, or if their civilization simply evolved into a new phase of sophistication. The Early Woodland People left no written records, so we have no idea what they called themselves. Certainly it wasn’t the Adena. This was the name of a nineteenth century estate owned by Thomas Worthington in Chillicothe on which remnants of this people were found. The Woodland People also traded from places afar and interned their dead in burial mounds. Their era stretches from about 1000 b.c. to 50 c.e. They may have constructed Serpent Mound in Peebles, Ohio.

The next humans to live in the area, the Middle Woodland people, did so from 50 to 450 c.e. and were known for building elaborate mounds. These people are called the Hopewell, who are named after Mordecai Hopewell, the man on whose land their mounds were excavated by Warren K. Moorehead. A museum information sign about them says, “Their settlements were not villages, but rather small hamlets.” Good to know except it doesn’t explain the difference between these two kinds of settlements, so I will. Hamlets have less than 100 people and rarely if ever have a central public building such as a church. Villages have central public buildings and usually a population between 100 and 1,000. Hopewell hamlets often had a mound in the center.

The next era of human habitation in Ohio is the Late Woodland period. It lasted from 450 to 1000 c.e. People of this time upgraded to villages, abandoned mound building, and started using bows and arrows. Well settled, they farmed and may have erected walls or dug ditches around their villages for defense. Corn was a staple of their diet, and their propensity for trade was far less than their predecessors.

The next era of human habitation in Ohio is the Late Woodland period. It lasted from 450 to 1000 c.e. People of this time upgraded to villages, abandoned mound building, and started using bows and arrows. Well settled, they farmed and may have erected walls or dug ditches around their villages for defense. Corn was a staple of their diet, and their propensity for trade was far less than their predecessors.

The next humans to live in the area, the Middle Woodland people, did so from 50 to 450 c.e. and were known for building elaborate mounds. These people are called the Hopewell, who are named after Mordecai Hopewell, the man on whose land their mounds were excavated by Warren K. Moorehead. A museum information sign about them says, “Their settlements were not villages, but rather small hamlets.” Good to know except it doesn’t explain the difference between these two kinds of settlements, so I will. Hamlets have less than 100 people and rarely if ever have a central public building such as a church. Villages have central public buildings and usually a population between 100 and 1,000. Hopewell hamlets often had a mound in the center.

The next era of human habitation in Ohio is the Late Woodland period. It lasted from 450 to 1000 c.e. People of this time upgraded to villages, abandoned mound building, and started using bows and arrows. Well settled, they farmed and may have erected walls or dug ditches around their villages for defense. Corn was a staple of their diet, and their propensity for trade was far less than their predecessors.

The next era of human habitation in Ohio is the Late Woodland period. It lasted from 450 to 1000 c.e. People of this time upgraded to villages, abandoned mound building, and started using bows and arrows. Well settled, they farmed and may have erected walls or dug ditches around their villages for defense. Corn was a staple of their diet, and their propensity for trade was far less than their predecessors.

In 1804 the land on which it resides was bought by Peter Rechner and made into a field he used to grow corn. Plowing often unearthed Native American artifacts, making it a popular stop for relic hunters. The City of Dayton bought the property in the mid-twentieth century, and in 1964 amateur archeologist John Allman began excavations of the area so that by 1967 he determined the Fort Ancient people had inhabited it. In 1970 the city of Dayton decided to build an incinerator on the land where SunWatch Indian Village now stands. The city gave the Dayton Society of Natural History permission do some archeological digs with the proviso it could kick them off the land with a mere three days’ notice. Many interesting things were found, so archeologist J. Heilman started a campaign to keep the incinerator from being built here. After the land was put on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975, the incinerator project was banned from here for good. Money from philanthropist Virginia Kettering of Dayton led to the construction of the Heilman-Kettering Interpretive Center, which opened on July 29, 1988, and is the building you enter to get to the village.

About sixty percent of the site was excavated by 1989 and from this work archeologists learned much about the village and its inhabitants. They found nineteen structures and many trash and storage sites. Also here were stockades and something that might have been sweat lodges. Their main crop was corn, which made up about half their diet. They also grew squash, sunflowers and beans. Although the corn, or maize, the SunWatch people ate was far more nutritious than the generically altered stuff we consume today, it wasn’t necessarily a good idea to eat as much of it as they did. It created health problems such as tooth decay, spina bifida (a defect to the spinal bones that can damage the spinal cord), and stunted growth.

Unhelpfully, someone determined their average lifespan was thirty-five to forty-five years old, one of the most useless statistics ever inflicted upon laypeople by scholars. All this number tells you is that the mortality rate was much higher than today, especially for infants and young children. When an excessive number of the young die, it brings down the average age considerably and gives the false impression that people over forty-five were so rare that those from this era were lucky to have seen an elderly person in their lifetimes. As the English are fond of saying, this is utter tosh. If you got into a time machine and visited the village at its height, you’d find people of all ages and see some who had managed to get into their eighties and even nineties.

About sixty percent of the site was excavated by 1989 and from this work archeologists learned much about the village and its inhabitants. They found nineteen structures and many trash and storage sites. Also here were stockades and something that might have been sweat lodges. Their main crop was corn, which made up about half their diet. They also grew squash, sunflowers and beans. Although the corn, or maize, the SunWatch people ate was far more nutritious than the generically altered stuff we consume today, it wasn’t necessarily a good idea to eat as much of it as they did. It created health problems such as tooth decay, spina bifida (a defect to the spinal bones that can damage the spinal cord), and stunted growth.

Unhelpfully, someone determined their average lifespan was thirty-five to forty-five years old, one of the most useless statistics ever inflicted upon laypeople by scholars. All this number tells you is that the mortality rate was much higher than today, especially for infants and young children. When an excessive number of the young die, it brings down the average age considerably and gives the false impression that people over forty-five were so rare that those from this era were lucky to have seen an elderly person in their lifetimes. As the English are fond of saying, this is utter tosh. If you got into a time machine and visited the village at its height, you’d find people of all ages and see some who had managed to get into their eighties and even nineties.

The final prehistoric era in Ohio lasted from 1000 to 1750 c.e. and is the Late Prehistoric Period. During this time in the area that is now northern Kentucky and southern Ohio, a culture related to those in Mississippi called Fort Ancient flourished. This name derives from a place near Cincinnati called Fort Ancient that is made up of earthen walls but probably wasn’t used as a fort. No matter. The name has stuck. One subgroup of the Fort Ancient people were those who created what is now known as SunWatch Indian Village in Dayton. They lived here from about 1150 to 1450 c.e., though whether continuously or intermittently isn’t known.

The SunWatch museum’s information sign titled “What is Fort Ancient Culture?” has this to say about them: the “Fort Ancient culture is defined by large villages, maize agriculture, and achieved social status. The Fort Ancient people did not build large mounds like the Adena and Hopewell but constructed small burial mounds near their villages. Evidence suggests that they built Serpent Mound.” Observant readers probably have noticed the last sentence in the quote contradicts the preceding one. Serpent Mound isn’t especially tall or wide, but it is long, making it indisputably large. Also, you may recall I mentioned Serpent Mound might have been made by the Adena. No one is sure who built it, but the Adena and Fort Ancient people are the most likely candidates. And since the Fort Ancient people didn’t build large mounds, it seems most likely the Adena people should receive the credit.

The SunWatch museum’s information sign titled “What is Fort Ancient Culture?” has this to say about them: the “Fort Ancient culture is defined by large villages, maize agriculture, and achieved social status. The Fort Ancient people did not build large mounds like the Adena and Hopewell but constructed small burial mounds near their villages. Evidence suggests that they built Serpent Mound.” Observant readers probably have noticed the last sentence in the quote contradicts the preceding one. Serpent Mound isn’t especially tall or wide, but it is long, making it indisputably large. Also, you may recall I mentioned Serpent Mound might have been made by the Adena. No one is sure who built it, but the Adena and Fort Ancient people are the most likely candidates. And since the Fort Ancient people didn’t build large mounds, it seems most likely the Adena people should receive the credit.

As you wander around the path in the village, you’ll notice a series of poles that appear to have no purpose. It’s these that gave the village its name. They were likely used like as a sundial and for astronomical observations to tell villagers exactly when to start the Spring planting as well as perform import ceremonies. The center of the village was kept relatively clear in a roughly 200 feet diameter, suggesting it was used for ceremonies, general gatherings, and maybe even for play.

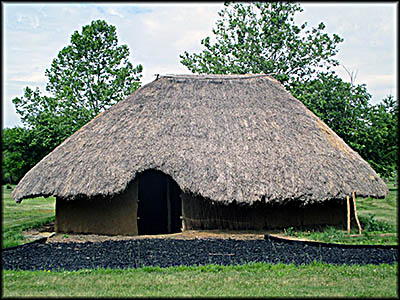

The museum’s reproduction houses are made of wooden frames covered with dried grass overlaid with mud. They are dark, hot, and would’ve have been filled with smoke and crammed with an extended family. Those in SunWatch Village who died were buried in a grave covered by a limestone slab, a sort of gravestone that was horizontal instead of vertical in relationship to the ground beneath it. Sometimes personal effects were buried with the departed. After its abandonment, SunWatch village was buried by the elements. Possibly it was deserted because local resources had been depleted, or maybe a cooling climate prompted its inhabitants to leave. The Fort Ancient people are probably the forebearers of historic Native American tribes such as the Cherokee and Shawnee.🕜

The museum’s reproduction houses are made of wooden frames covered with dried grass overlaid with mud. They are dark, hot, and would’ve have been filled with smoke and crammed with an extended family. Those in SunWatch Village who died were buried in a grave covered by a limestone slab, a sort of gravestone that was horizontal instead of vertical in relationship to the ground beneath it. Sometimes personal effects were buried with the departed. After its abandonment, SunWatch village was buried by the elements. Possibly it was deserted because local resources had been depleted, or maybe a cooling climate prompted its inhabitants to leave. The Fort Ancient people are probably the forebearers of historic Native American tribes such as the Cherokee and Shawnee.🕜