Exhibit A

Exhibit B

Exhibit C

Exhibit D

Exhibit E

Ladies and Gentlemen, welcome to the Charleston Museum, the oldest museum in all of North America. Look up and you see hanging from the ceiling an Atlantic right whale (Exhibit A) that swam into Charleston Harbor on January 7, 1880. The good citizens of this fine city enthusiastically greeted it with between fifty and sixty rowboats, four steam tugs, and many other water-going vessels, then killed and harvested it for its valuable blubber and oil. But shed no tears. The then-curator of this very museum, Gabriel Manigault, gathered up its bones, assembled them to a size of just under thirty-six feet, then put them on display. As you gaze at this wonder, move your eyes to the back of the building and hanging from the ceiling you will see a beautiful electric chandelier (Exhibit B) from the now-closed Fort Sumpter Hotel. Chandelier enthusiasts will undoubtedly want to know that it has a total of 4,365 prisms.

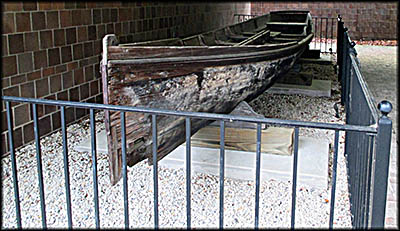

Before you came through our doors, you might have noticed we have on display a steam engine (Exhibit C) dating from the 1850s. Made by the Charleston business Cameron, McDermid and Mustard (the last not having killed Professor Plum despite ugly rumors to the contrary), it was used to thresh and mill rice at Fairlawn Planation. Beside this we have Bessie (Exhibit D), a plantation barge carved from a single log used by the White Oak Planation along the North Santee River.

Before you came through our doors, you might have noticed we have on display a steam engine (Exhibit C) dating from the 1850s. Made by the Charleston business Cameron, McDermid and Mustard (the last not having killed Professor Plum despite ugly rumors to the contrary), it was used to thresh and mill rice at Fairlawn Planation. Beside this we have Bessie (Exhibit D), a plantation barge carved from a single log used by the White Oak Planation along the North Santee River.

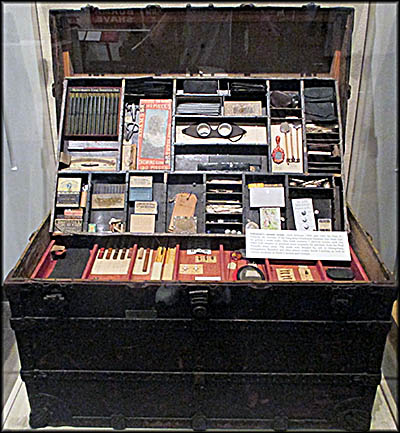

Here is a favorite of mine. This salesman’s trunk (Exhibit I) was used by Paul E. Trouche, Sr., from 1890 to 1901 to promote his retail store. He moved it by rail and went as far afield as Beaufort, Orangeberg, and Georgetown in South Carolina, then beyond the state borders into Georgia and North Carolina. Some of the items you see within are a hand mirror, fountain pens, chewing gum, cigarettes, change purse, clothes pins, dice, marbles, and swan bill hooks and eyes for sewing. We will briefly return to the subject of sewing later in our tour.

Now let’s take a look at the origins of the Holy City, so called because Charleston has so many churches. Its beginnings weren’t so hallowed. Imagine one day you’re minding your own business and strangers with pale skin arrive. At first they just want to trade, but then they start to build houses and take over your land. They bring with them diseases that decimate your population. The original inhabitants of the Carolina coastlands were forced to move inland. Wars broke out. Eventually the power of the pale skins was too much and slowly but surely the native people disappeared from sight.

So why did these pale skins (the English) come? King Charles II granted eight men, known collectively as the Lords Proprietors, a vast swath of North American land as a reward for their service to him. The English didn’t know what awaited them here, but no matter. The Lords Proprietors, being all aristocrats, thought it an excellent idea to set up a feudal system in their new colony, Carolina, based on land grants to colonists. Most of the Proprietors never set foot in the place. An exception was Lord Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who established a 12,000 acre planation called St. Giles Kusso (abandoned in 1685). Back home, Cooper get into trouble for opposing Charles II’s brother, James, from becoming king. Charged with treason, he spent time in the Tower of London. After the charges were dropped, he moved to the Netherlands where he died in exile. It’s from him that the two rivers surrounding Charleston received their names.

The Lords Proprietors were never good managers, their feudal system didn’t work, and by 1719 Carolina Colony came under royal rule. It split into two parts, North and South, ten years later. The original Charles Town was abandoned and relocated on the peninsula between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. It originally had walls for protection, although being a sea port with a natural harbor, that didn’t always help.

Now let’s take a look at the origins of the Holy City, so called because Charleston has so many churches. Its beginnings weren’t so hallowed. Imagine one day you’re minding your own business and strangers with pale skin arrive. At first they just want to trade, but then they start to build houses and take over your land. They bring with them diseases that decimate your population. The original inhabitants of the Carolina coastlands were forced to move inland. Wars broke out. Eventually the power of the pale skins was too much and slowly but surely the native people disappeared from sight.

So why did these pale skins (the English) come? King Charles II granted eight men, known collectively as the Lords Proprietors, a vast swath of North American land as a reward for their service to him. The English didn’t know what awaited them here, but no matter. The Lords Proprietors, being all aristocrats, thought it an excellent idea to set up a feudal system in their new colony, Carolina, based on land grants to colonists. Most of the Proprietors never set foot in the place. An exception was Lord Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who established a 12,000 acre planation called St. Giles Kusso (abandoned in 1685). Back home, Cooper get into trouble for opposing Charles II’s brother, James, from becoming king. Charged with treason, he spent time in the Tower of London. After the charges were dropped, he moved to the Netherlands where he died in exile. It’s from him that the two rivers surrounding Charleston received their names.

The Lords Proprietors were never good managers, their feudal system didn’t work, and by 1719 Carolina Colony came under royal rule. It split into two parts, North and South, ten years later. The original Charles Town was abandoned and relocated on the peninsula between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. It originally had walls for protection, although being a sea port with a natural harbor, that didn’t always help.

Pirates became a problem. Driven from the Caribbean by the Royal Navy, many took to hiding among the coasts of North and South Carolina, which is filled with barrier islands. In June 1718 four pirate ships began a blockade of Charleston harbor. Their captain was none other then Edward Teach, better know to history as Blackbeard. He captured several prominent citizens of Charleston, raided up to nine ships, and refused to leave and release his prisoners until receiving a chest of medicine that was possibly used to treat sexually transmitted diseases.

Exhibit F

Once given what he demanded, off he went, only to be tracked down and killed by a force sent out by Virginia’s governor, Alexander Spotswood. South Carolina’s governor, Robert Johnson, sent his own man, Colonel William Rhett, to hunt pirates. He didn’t find Blackbeard but did catch a former subordinate, Stede Bonnet, whose ship and crew had been present at the blockade of Charleston.

Charleston Harbor was a major port for the importation of British goods. Many American items flowed out, but this was mostly natural resources such as deer skins, livestock, lumber, and cash crops. Colonists were forbidden from trading with anyone but Britain or other colonies, so much smuggling of Spanish and French items into the colony occurred. The Crown also forbade its American colonies from producing most finished goods, instead forcing colonists to buy British-made ones. With clothes being one of the commodities not produced en masse in the colonies, it meant that in the eighteenth century sewing was valuable skill. Here we have a sewing case made between 1790 and 1820 (Exhibit J).

Charleston Harbor was a major port for the importation of British goods. Many American items flowed out, but this was mostly natural resources such as deer skins, livestock, lumber, and cash crops. Colonists were forbidden from trading with anyone but Britain or other colonies, so much smuggling of Spanish and French items into the colony occurred. The Crown also forbade its American colonies from producing most finished goods, instead forcing colonists to buy British-made ones. With clothes being one of the commodities not produced en masse in the colonies, it meant that in the eighteenth century sewing was valuable skill. Here we have a sewing case made between 1790 and 1820 (Exhibit J).

When they first established the colony of Carolina, the Lords Proprietors wanted colonists to grow tropical crops, but colder than expected winters ended that idea. So other crops were needed. In the 1740s, Elizabeth Lucas Pickney developed a strain of indigo that British textile firms used for the color blue. This was only profitable so long as it was subsided by the British government, which stopped that after the Revolution.

Although we Charlestonians are proud of our city and heritage, it would be remiss of this museum to not cover the more unsavory parts of our past, especially since so many whites benefited from the work of enslaved Blacks. In the first year of Carolina Colony, slaves were imported from the West Indies. By 1708 the colony’s enslaved population outnumbered whites. Charleston itself became a major gateway of slave importation. Between 1700 and 1775, forty percent of those brought to America arrived via our city.

While the majority of slaves were put to work on plantations, Charleston itself relied on its own enslaved population for domestic labor. Slaves took the roles of paid servants such as butlers and nurses. Urban slaves often had freedom of movement in the city and some lived outside the city limits. According the one of the museum’s information signs, “free and enslaved black men dominated building trades as brick masons, carpenters, painters, and plasterers while others worked as tailors, butchers … mechanics, and ship carpenters. Women were generally employed as seamstresses, washerwomen, cooks, hucksters [probably peddlers in this context], and servants.” Free and enslaved Blacks were the city’s primary fishermen. Slaves were also adept at making bricks, most of which were produced in the colony rather than imported. Note that the ones here on display (Exhibit K) have the finger marks of their enslaved makers.

Although we Charlestonians are proud of our city and heritage, it would be remiss of this museum to not cover the more unsavory parts of our past, especially since so many whites benefited from the work of enslaved Blacks. In the first year of Carolina Colony, slaves were imported from the West Indies. By 1708 the colony’s enslaved population outnumbered whites. Charleston itself became a major gateway of slave importation. Between 1700 and 1775, forty percent of those brought to America arrived via our city.

While the majority of slaves were put to work on plantations, Charleston itself relied on its own enslaved population for domestic labor. Slaves took the roles of paid servants such as butlers and nurses. Urban slaves often had freedom of movement in the city and some lived outside the city limits. According the one of the museum’s information signs, “free and enslaved black men dominated building trades as brick masons, carpenters, painters, and plasterers while others worked as tailors, butchers … mechanics, and ship carpenters. Women were generally employed as seamstresses, washerwomen, cooks, hucksters [probably peddlers in this context], and servants.” Free and enslaved Blacks were the city’s primary fishermen. Slaves were also adept at making bricks, most of which were produced in the colony rather than imported. Note that the ones here on display (Exhibit K) have the finger marks of their enslaved makers.

Exhibit J

Exhibit K

Masters often hired out their urban slaves to others, and some slaves were allowed to hire themselves out as well. For a master to rent his slave, he or she had to purchase a slave badge (Exhibit L) from the city treasurer that included a registration number, the year of its issue, and the slave’s skills, such as carpenter or porter. No other place in the English colonies had these badges. Free Blacks were required to wear their own badges from 1783 to 1789 (Exhibit M).

This type of control was done mainly out of fear. Whites were well aware that not only did the colony’s enslaved population outnumber them, slaves didn’t especially like their condition of servitude and were prone to run away or, worse, rebel. Once such rebellion occurred along the Stono River south of Charleston. On the morning of September 9, 1739, twenty slaves originally from Angola were left unsupervised while digging a ditch. They surprised and killed a commissioner of highways, John Gibbs, then killed Robert Bathurst, owner of Hutchenson’s Store, and his employee. From the store they procured arms and marched south, killing more whites.

The escapees marched with banners that said, “Liberty!” They most likely desired to reach St. Augustine, Florida, then a Spanish colony where runaway slaves could gain their freedom. Along the way they gathered more followers, some not necessarily being willing participants. The insurrection grew to about 100 souls. Whites quickly organized a militia that easily defeated the rebels, killing or capturing many. Others who escaped were tracked down in the next few months. One managed to evade capture for three years. After this incident, the Negro Act of 1740 was passed to further restrict the movement of slaves. For over a century hereafter fear of slave uprisings only increased.

South Carolina’s Lowcountry depended heavily on slave labor for its many plantations. The Southern slave economy is usually associated with cotton, but the cash crop that made many Carolinian colonials rich was rice. Plantation owners who grew this food preferred to import slaves from specific regions of Africa: its Gold Coast, Congo-Angola region (where the Stono rebels were from), the Windward Coast, and Senegambia. This was because natives of these regions knew how to cultivate rice and were excellent boat and fishermen.

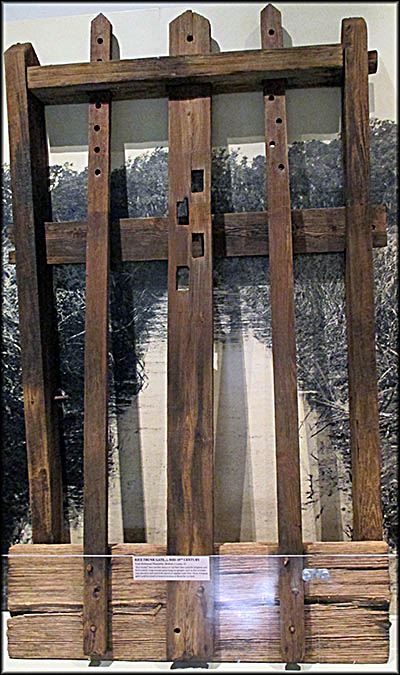

Rice plantations usually had an overseer under whom were trusted slaves known as drivers. It was they who were responsible for overseeing all aspects of the growing and harvesting of rice. Because rice plantations were far more labor intensive than, say, a cotton plantation, slaves were assigned tasks based on their skill set. To grow rice, it needs to be planted in dry land and be inundated in water as it grows. The seasonal rains were backwards to this need, so many ditches to move water were dug by groups with this specific task, usually strong men. Others did the sowing of the rice and were expected to cover half a acre a day. The flooding and draining of fields was controlled by a rice trunk gate (Exhibit N). Weeding was ever a challenge and a hard job. Once the rice was harvested, it was milled by hand using a mortar and pestle.

This type of control was done mainly out of fear. Whites were well aware that not only did the colony’s enslaved population outnumber them, slaves didn’t especially like their condition of servitude and were prone to run away or, worse, rebel. Once such rebellion occurred along the Stono River south of Charleston. On the morning of September 9, 1739, twenty slaves originally from Angola were left unsupervised while digging a ditch. They surprised and killed a commissioner of highways, John Gibbs, then killed Robert Bathurst, owner of Hutchenson’s Store, and his employee. From the store they procured arms and marched south, killing more whites.

The escapees marched with banners that said, “Liberty!” They most likely desired to reach St. Augustine, Florida, then a Spanish colony where runaway slaves could gain their freedom. Along the way they gathered more followers, some not necessarily being willing participants. The insurrection grew to about 100 souls. Whites quickly organized a militia that easily defeated the rebels, killing or capturing many. Others who escaped were tracked down in the next few months. One managed to evade capture for three years. After this incident, the Negro Act of 1740 was passed to further restrict the movement of slaves. For over a century hereafter fear of slave uprisings only increased.

South Carolina’s Lowcountry depended heavily on slave labor for its many plantations. The Southern slave economy is usually associated with cotton, but the cash crop that made many Carolinian colonials rich was rice. Plantation owners who grew this food preferred to import slaves from specific regions of Africa: its Gold Coast, Congo-Angola region (where the Stono rebels were from), the Windward Coast, and Senegambia. This was because natives of these regions knew how to cultivate rice and were excellent boat and fishermen.

Rice plantations usually had an overseer under whom were trusted slaves known as drivers. It was they who were responsible for overseeing all aspects of the growing and harvesting of rice. Because rice plantations were far more labor intensive than, say, a cotton plantation, slaves were assigned tasks based on their skill set. To grow rice, it needs to be planted in dry land and be inundated in water as it grows. The seasonal rains were backwards to this need, so many ditches to move water were dug by groups with this specific task, usually strong men. Others did the sowing of the rice and were expected to cover half a acre a day. The flooding and draining of fields was controlled by a rice trunk gate (Exhibit N). Weeding was ever a challenge and a hard job. Once the rice was harvested, it was milled by hand using a mortar and pestle.

Rice made Carolina Colony’s Lowcountry wealthier than anywhere else in the North America, with Carolinian planters being four to ten times richer other colonists. In the early days of colonial South Carolina, plantations grew red rice from the East Indies and Madagascar. Soon enough someone realized Asian white rice grew better, so that became the dominate type. In the 1770s a short grain variety of rice known as Carolina Gold was developed. Rice cultivation could only be done along South Carolina’s and Georgia’s tidal rivers, and only 550 planters grew this crop. By the nineteenth century funding the creation of a rice plantation was out of the reach of most. Rice planters had “old money.” They also owned the most slaves, without whom they would have had nothing.

During the Antebellum era, Georgia and South Carolina continued to grow ninety percent of the nation’s rice. At the dawn of the Civil War, there were 227 rice plantations covering 70,000 acres and producing almost 100 million pounds a year. The Civil War caused the decline of rice production in the region. Those plantations not outright destroyed or devastated during the war struggled to pay even low wages to its African American work force to grow this crop, especially during Reconstruction when former slaves had the power to demand higher pay. Rice production continued but a series extreme storms and hurricanes between 1893 and 1911 destroyed much of the necessary dike system, making further growing of this crop impossible without a massive investment in infrastructure. A museum information reported that “the last commercial rice crop in the state [was] grown in 1927.”

The wealthiest of planters became the equivalent of top tier South Carolinian aristocracy. To emulate their English brethren, they spent lavishly on imported luxury goods from Britain and Asia. Locally they bought from the best furniture makers, silversmiths, and so forth. Having one’s portrait painted was also a status symbol. They also liked to plant formal gardens because that’s what large English estates had.

Another affect the elite of South Carolina and Georgia adopted from the English aristocratic was a love of dueling. A perceived slight or outright insult could result in two men facing one another in a field, usually armed with dueling pistols such as you see here (Exhibit O). These were made in England by gunsmith William Jacot. Although dueling was officially outlawed in 1812, that didn’t stop Charleston residents Ludlow Cohen and Rich Aiken from fighting it out at Brampton Planation in Georgia on August 18, 1870. They had quarreled over a sailboat race and decided only a duel to the death would settle the matter. Borrowing pistols from A.G. Guerard, they fired and missed one another four times until Cohen killed Aiken with his fifth shot. No deaths by duel have since been reported in Georgia.

Editor’s Note: The author of this work is not really a Charlestonian and decided to write this travel log from the perspective of a homegrown tour guide in the museum because he felt this format would allow him to best highlight some of its exhibits and artifacts in a coherent way. Most visitors to this museum take a self-guided tour. Despite the fiction that this log was written by a resident of Charleston, everything in it is factual and based on the information provided by the museum’s information signs and artifacts.🕜

During the Antebellum era, Georgia and South Carolina continued to grow ninety percent of the nation’s rice. At the dawn of the Civil War, there were 227 rice plantations covering 70,000 acres and producing almost 100 million pounds a year. The Civil War caused the decline of rice production in the region. Those plantations not outright destroyed or devastated during the war struggled to pay even low wages to its African American work force to grow this crop, especially during Reconstruction when former slaves had the power to demand higher pay. Rice production continued but a series extreme storms and hurricanes between 1893 and 1911 destroyed much of the necessary dike system, making further growing of this crop impossible without a massive investment in infrastructure. A museum information reported that “the last commercial rice crop in the state [was] grown in 1927.”

The wealthiest of planters became the equivalent of top tier South Carolinian aristocracy. To emulate their English brethren, they spent lavishly on imported luxury goods from Britain and Asia. Locally they bought from the best furniture makers, silversmiths, and so forth. Having one’s portrait painted was also a status symbol. They also liked to plant formal gardens because that’s what large English estates had.

Another affect the elite of South Carolina and Georgia adopted from the English aristocratic was a love of dueling. A perceived slight or outright insult could result in two men facing one another in a field, usually armed with dueling pistols such as you see here (Exhibit O). These were made in England by gunsmith William Jacot. Although dueling was officially outlawed in 1812, that didn’t stop Charleston residents Ludlow Cohen and Rich Aiken from fighting it out at Brampton Planation in Georgia on August 18, 1870. They had quarreled over a sailboat race and decided only a duel to the death would settle the matter. Borrowing pistols from A.G. Guerard, they fired and missed one another four times until Cohen killed Aiken with his fifth shot. No deaths by duel have since been reported in Georgia.

Editor’s Note: The author of this work is not really a Charlestonian and decided to write this travel log from the perspective of a homegrown tour guide in the museum because he felt this format would allow him to best highlight some of its exhibits and artifacts in a coherent way. Most visitors to this museum take a self-guided tour. Despite the fiction that this log was written by a resident of Charleston, everything in it is factual and based on the information provided by the museum’s information signs and artifacts.🕜

Exhibit G

Exhibit H

Exhibit I

Exhibit L

Exhibit M

Exhibit N

Exhibit O

Bank Teller's Counter, c. 1895

Cotton Bale

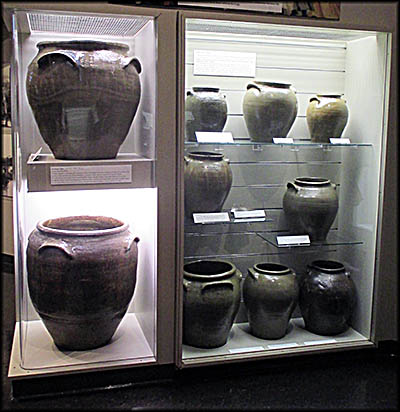

Storage Jars

George Washington's Christening Cup

Confederate Money

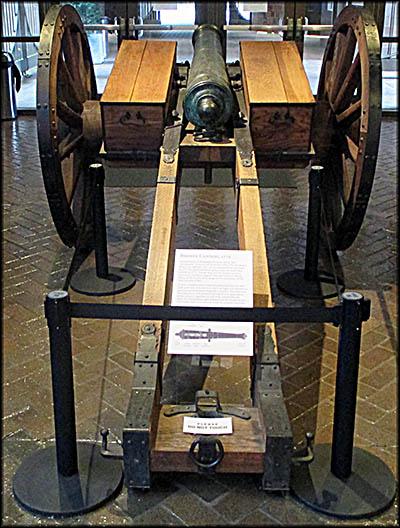

The bronze cannon (Exhibit E) pointed at one set of our doors offers no danger to visitors. James Byers made this in 1775 in Philadelphia. It was used during the War of Independence and for some years “guarded” Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston. The carriage upon which it now sets was constructed in 1976.

Look up again and notice the statue of Charity (Exhibit F), or at least what’s left of her. She once proudly stood in a cupola at the Charleston Orphan House. This structure was erected between 1792 and 1794 to house all the orphans left behind after their parents perished in a yellow fever epidemic. Charity was added to the orphanage during its 1853–1854 expansion. The orphanage building was demolished in 1952. Charity is the only survivor.

Let us move to the Bunting Natural History Gallery and gaze upon the skeleton of Thecachampsa carolinensis (Exhibit G), a type of crocodile that lived between twenty-six to twenty-eight million years ago. What you see here is a cast that is eighteen feet long, The original was even bigger. Let us move on to this excellent example of taxidermy, our polar bear (Exhibit H), which was killed by Henry J. Blackford near Kotzebue, Alaska.

Look up again and notice the statue of Charity (Exhibit F), or at least what’s left of her. She once proudly stood in a cupola at the Charleston Orphan House. This structure was erected between 1792 and 1794 to house all the orphans left behind after their parents perished in a yellow fever epidemic. Charity was added to the orphanage during its 1853–1854 expansion. The orphanage building was demolished in 1952. Charity is the only survivor.

Let us move to the Bunting Natural History Gallery and gaze upon the skeleton of Thecachampsa carolinensis (Exhibit G), a type of crocodile that lived between twenty-six to twenty-eight million years ago. What you see here is a cast that is eighteen feet long, The original was even bigger. Let us move on to this excellent example of taxidermy, our polar bear (Exhibit H), which was killed by Henry J. Blackford near Kotzebue, Alaska.

Inside the Natural History Portion of the Museum

Charleston Museum