EBENEZER ZANE

In early Fall 1769, Ebenezer Zane and his brothers Jonathan and Silas trekked west from their home at Redstone Fort (modern Brownsville, Pennsylvania) to the Ohio River looking for land to establish a new settlement. They found the perfect spot where Wheeling Creek pours into the Ohio River at which they along with several friends constructed dwellings. In the spring of 1770 Ebenezer’s wife and daughter arrived. Within a few years the settlement became Wheeling, then part of Virginia but now West Virginia.

EBENEZER ZANE: OHIO PIONEER BY PROXY

Copyright © 2021 by Mark Strecker.

Ebenezer Zane's Stone House Built about 1800

The Brown Collection of Photographs. Ohio County Public Library.

The Brown Collection of Photographs. Ohio County Public Library.

Bird's Eye View of Wheeling, WV, c. 1909

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Norborne Berkeley, Baron de Botetourt.

Statue at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA.

Library of Congress

Statue at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA.

Library of Congress

There was one small problem: Zane and his brothers were squatters with no right claim to this land. The Proclamation of 1763 issued by the Privy Council forbade British colonists from either moving into or speculating on lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. This vexed the two to five percent of Virginia’s elite for whom land speculation made up a considerable amount of their income. Thanks to the Proclamation, all their land claims were voided. Squatters like Zane made their blood boil because if ever they got their hands on the land that he and others had taken, it would be hard to remove them.

A glimmer of hope that the Proclamation might be rescinded came in 1768 when the British purchased land west of the Appalachians from the Iroquois via the Treaty at Fort Stanwix. One land speculator, Thomas Walker, was so certain that the Privy Council would reverse the Proclamation, he revived his land speculation venture, the Loyal Company, from which Thomas Jefferson asked to purchase 5,000 acres. The trouble was much of the land bought from the Iroquois was claimed by the Cherokees, Shawnees, Mingoes, and Delawares, and they were disinclined to give it up. The Privy Council knew if colonists flooded the region, an unwanted war with these Native American tribes would erupt.

On April 25, 1769, the fear of a possible coalition of Ohio Valley tribes banning together prompted Virginian governor Norborne Berkeley, the baron de Botetourt, to void the latest surveying efforts of the Loyal Company and similar operations. His Executive Council refused to recognize all land claims made from late 1768 to early 1769. Speculators affected by this included Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and George Washington.

Governor Botetourt died in October 1770. When his permanent replacement, John Murray, the Lord Dunmore, took office in late 1771, he issued land grants to a few veterans of the Seven Years’ War that Henry, Jefferson and other land speculators quickly bought up. Washington, fearing the grants wouldn’t be recognized by the British government, declined to buy any. His prediction proved to be true. In a letter dated April 6, 1774, colonial secretary William Legge, the earl of Dartmouth, wrote Lord Dunmore telling him veterans weren’t entitled to this land. Doubling down in Britain’s effort to keep colonists out of forbidden territory, Parliament granted Quebec all land west of the Ohio River.

With so much money at stake, Virginia’s land speculators weren’t going give up without a fight. Knowing the Privy Council refused to revoke the Proclamation for fear of Native American retaliation, they needed an excuse to launch a war against them so they could take the land for themselves. It was provided by Mingo chief John Logan’s 1774 raids against Virginians in retaliation for the murder of some of his family at the hand of an illegal white militia. Despite the fact the Shawnees and Mingoes had nothing to do with Logan’s actions, in October 1774 the Virginians attacked their towns.

A glimmer of hope that the Proclamation might be rescinded came in 1768 when the British purchased land west of the Appalachians from the Iroquois via the Treaty at Fort Stanwix. One land speculator, Thomas Walker, was so certain that the Privy Council would reverse the Proclamation, he revived his land speculation venture, the Loyal Company, from which Thomas Jefferson asked to purchase 5,000 acres. The trouble was much of the land bought from the Iroquois was claimed by the Cherokees, Shawnees, Mingoes, and Delawares, and they were disinclined to give it up. The Privy Council knew if colonists flooded the region, an unwanted war with these Native American tribes would erupt.

On April 25, 1769, the fear of a possible coalition of Ohio Valley tribes banning together prompted Virginian governor Norborne Berkeley, the baron de Botetourt, to void the latest surveying efforts of the Loyal Company and similar operations. His Executive Council refused to recognize all land claims made from late 1768 to early 1769. Speculators affected by this included Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and George Washington.

Governor Botetourt died in October 1770. When his permanent replacement, John Murray, the Lord Dunmore, took office in late 1771, he issued land grants to a few veterans of the Seven Years’ War that Henry, Jefferson and other land speculators quickly bought up. Washington, fearing the grants wouldn’t be recognized by the British government, declined to buy any. His prediction proved to be true. In a letter dated April 6, 1774, colonial secretary William Legge, the earl of Dartmouth, wrote Lord Dunmore telling him veterans weren’t entitled to this land. Doubling down in Britain’s effort to keep colonists out of forbidden territory, Parliament granted Quebec all land west of the Ohio River.

With so much money at stake, Virginia’s land speculators weren’t going give up without a fight. Knowing the Privy Council refused to revoke the Proclamation for fear of Native American retaliation, they needed an excuse to launch a war against them so they could take the land for themselves. It was provided by Mingo chief John Logan’s 1774 raids against Virginians in retaliation for the murder of some of his family at the hand of an illegal white militia. Despite the fact the Shawnees and Mingoes had nothing to do with Logan’s actions, in October 1774 the Virginians attacked their towns.

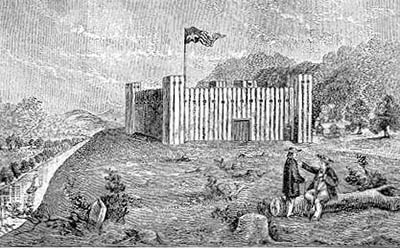

Fort Henry

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

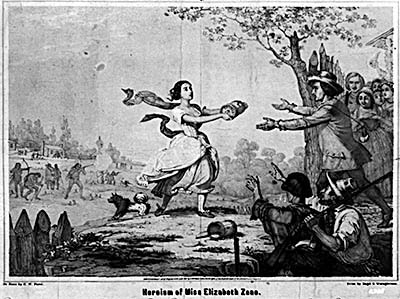

"Heroism of Miss Elizabeth Zane" (c. 1851)

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

John McIntire. Painted by James Pierce Barton.

Pioneer & Historical Society Collection

Pioneer & Historical Society Collection

General Anthony Wayne. 1878 print.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

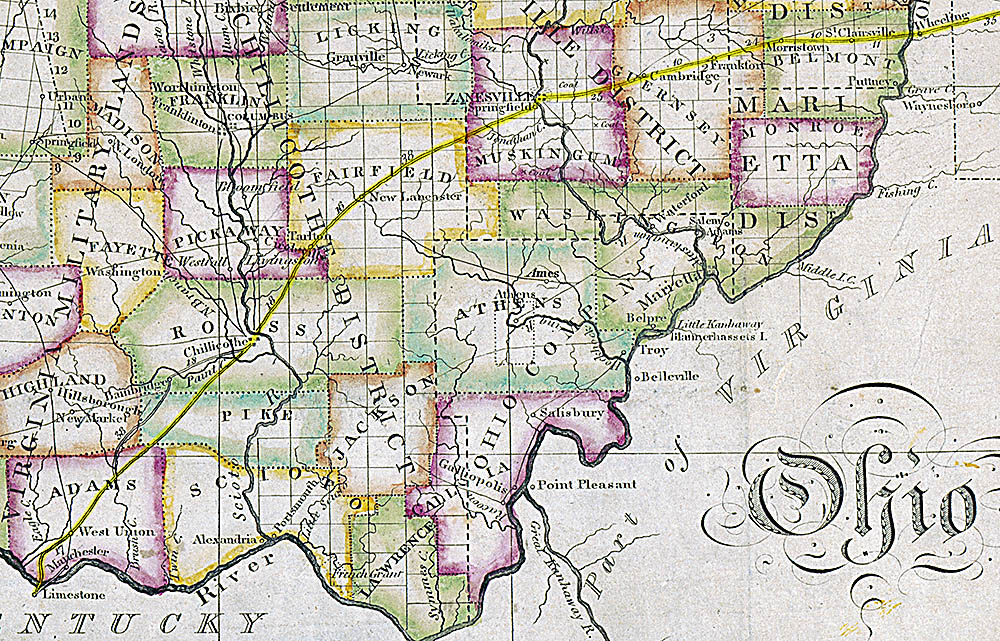

Zane's Trace. From A Map of the United States Exhibiting Post Roads & Distances...

by Abraham Barker and William Bradley. Published by Abraham Bradley, Jr., 1796?

Library of Congress

by Abraham Barker and William Bradley. Published by Abraham Bradley, Jr., 1796?

Library of Congress

Louis Phillipe

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

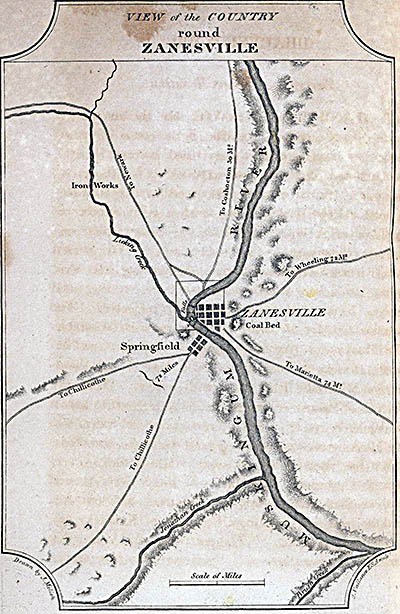

"View of the Country Round Zanesville" 1812.

Dave Rumsey Collection

Dave Rumsey Collection

Known as Lord Dunmore’s War, Ebenezer Zane joined the Virginian militia and was appointed a colonel. Despite the fact Wheeling was an illegal settlement, he was tasked with building Fort Fincastle there for its defense. By month’s end, Virginia’s overwhelming force of 2,000 men forced the Shawnee to give up all land east of the Ohio River. Unfortunately for Virginia’s land speculators, the Privy Council didn’t repeal the Proclamation in large part because parts of the colonies were in open rebellion against the Crown.

Zane was an enthusiastic supporter of independence from Britain, in part because such a break would likely result in giving him a legal claim to the land he had settled upon. He remained in charge of the militia at Fort Fincastle, which was renamed Fort Henry in honor of independent Virginia’s first homegrown governor, Patrick Henry. Yet Zane was no professional solider. His primary occupation was that of hunter. Born in Virginia on October 7, 1747, he was educated in public schools, giving him the ability to read and write, the latter resulting in some well-composed letters. A short but strong, dark-complexioned man, after the Revolution he became a land speculator, though he rarely made improvements to what he bought, instead waiting for the price to go up so he could sell.

He and his wife, Elizabeth McCulloch, married in 1768 and went on to have thirteen children. They lived in Wheeling for nearly all their married life. Elizabeth, born on October 30, 1748, was an energetic woman who ran a general store, inn, and ferry service. A devout Methodist, she was also a skilled nurse. Once she extracted seventeen bullets from a man named Mills who while fishing had been shot by Native Americans.

On August 31, 1777, British loyalist Simon Girty led a force of three or four hundred (sources vary) Shawnee, Wyandot, and Mingo warriors to the gates of Fort Henry. Girty demanded that it surrender and gave its occupants fifteen minutes to do so. Although the fort was commanded by Colonel David Shepherd, Zane gave its reply, telling Girty that everyone in the fort would rather die than give up their liberty. This despite the fact it was defended by twelve men and boys as well as an unspecified number of women. It had not a single cannon, just a tree trunk made to look like one. For twenty-three hours the attackers tried and failed to breach the fort’s tall walls. Incoming reinforcements caused their departure, during which they absconded with many of the Wheeling’s hogs and cattle.

Although Lord Cornwallis surrendered to General Washington on October 19, 1781, neither he nor anyone else present had any idea historians would consider this moment the end of the American Revolution. Fighting continued for just over a year. On September 11, 1782, the British and their Native American allies arrived at Fort Henry and demanded its surrender. This was refused. The attackers consisted of fifty British irregulars from Butler’s Rangers and between 250 and 350 Native Americans from a variety of tribes under the command of Captain Andrew Brandt.

Zane oversaw the militia tasked with defending the fort. He had been forewarned by spy John Lyn that the attack was coming, so he sent word to neighboring settlements, then ordered nearly everyone in town to repair to the fort. He remained in his house, which was about sixty yards from the fort and designed like a blockhouse complete with loopholes for rifles. Here military supplies were kept. Staying with Zane were Andrew Scott, George Greer, Molly Scott, Miss McColloch, a black man named Sam (he may have been a slave) and Zane’s wife, Elizabeth. Ebenezer put his younger brother, Colonel Silas, in charge of the fort proper. A boat from Pittsburgh heading to Louisville with cannonballs happened to be passing, so its captain and crew disembarked to help reinforce the fort.

The first attempt to breech its walls was made at midnight. Others followed. Neither battering rams aimed to breaking the gate down nor attempts to burn the fort and Zane’s house were successful. In the fort proper gunpowder was running low. Someone needed to dash to Zane’s house to get another keg. Ebenezer’s sister, Betty Zane, volunteered to do so because no man in the fort could be spared. Just twenty-three at the time, she had recently returned from school in Philadelphia.

Removing extra garments that might impede her, her dash from the fort to her brother’s house went smoothly because the Native Americans watching her thought a woman posed no threat. Inside, Zane had a keg of gunpowder ready but rather give it to her, he made a sack out of a tablecloth and poured the powder into that. On her return trip the attackers realized what she was about and fired at her, leaving nothing behind but a single bullet hole in the tablecloth. The fort used the extra gunpowder to fire its one cannon, repelling the besiegers until reinforcements came. Their arrived caused the attacking force to remove itself from the area.

Zane was an enthusiastic supporter of independence from Britain, in part because such a break would likely result in giving him a legal claim to the land he had settled upon. He remained in charge of the militia at Fort Fincastle, which was renamed Fort Henry in honor of independent Virginia’s first homegrown governor, Patrick Henry. Yet Zane was no professional solider. His primary occupation was that of hunter. Born in Virginia on October 7, 1747, he was educated in public schools, giving him the ability to read and write, the latter resulting in some well-composed letters. A short but strong, dark-complexioned man, after the Revolution he became a land speculator, though he rarely made improvements to what he bought, instead waiting for the price to go up so he could sell.

He and his wife, Elizabeth McCulloch, married in 1768 and went on to have thirteen children. They lived in Wheeling for nearly all their married life. Elizabeth, born on October 30, 1748, was an energetic woman who ran a general store, inn, and ferry service. A devout Methodist, she was also a skilled nurse. Once she extracted seventeen bullets from a man named Mills who while fishing had been shot by Native Americans.

On August 31, 1777, British loyalist Simon Girty led a force of three or four hundred (sources vary) Shawnee, Wyandot, and Mingo warriors to the gates of Fort Henry. Girty demanded that it surrender and gave its occupants fifteen minutes to do so. Although the fort was commanded by Colonel David Shepherd, Zane gave its reply, telling Girty that everyone in the fort would rather die than give up their liberty. This despite the fact it was defended by twelve men and boys as well as an unspecified number of women. It had not a single cannon, just a tree trunk made to look like one. For twenty-three hours the attackers tried and failed to breach the fort’s tall walls. Incoming reinforcements caused their departure, during which they absconded with many of the Wheeling’s hogs and cattle.

Although Lord Cornwallis surrendered to General Washington on October 19, 1781, neither he nor anyone else present had any idea historians would consider this moment the end of the American Revolution. Fighting continued for just over a year. On September 11, 1782, the British and their Native American allies arrived at Fort Henry and demanded its surrender. This was refused. The attackers consisted of fifty British irregulars from Butler’s Rangers and between 250 and 350 Native Americans from a variety of tribes under the command of Captain Andrew Brandt.

Zane oversaw the militia tasked with defending the fort. He had been forewarned by spy John Lyn that the attack was coming, so he sent word to neighboring settlements, then ordered nearly everyone in town to repair to the fort. He remained in his house, which was about sixty yards from the fort and designed like a blockhouse complete with loopholes for rifles. Here military supplies were kept. Staying with Zane were Andrew Scott, George Greer, Molly Scott, Miss McColloch, a black man named Sam (he may have been a slave) and Zane’s wife, Elizabeth. Ebenezer put his younger brother, Colonel Silas, in charge of the fort proper. A boat from Pittsburgh heading to Louisville with cannonballs happened to be passing, so its captain and crew disembarked to help reinforce the fort.

The first attempt to breech its walls was made at midnight. Others followed. Neither battering rams aimed to breaking the gate down nor attempts to burn the fort and Zane’s house were successful. In the fort proper gunpowder was running low. Someone needed to dash to Zane’s house to get another keg. Ebenezer’s sister, Betty Zane, volunteered to do so because no man in the fort could be spared. Just twenty-three at the time, she had recently returned from school in Philadelphia.

Removing extra garments that might impede her, her dash from the fort to her brother’s house went smoothly because the Native Americans watching her thought a woman posed no threat. Inside, Zane had a keg of gunpowder ready but rather give it to her, he made a sack out of a tablecloth and poured the powder into that. On her return trip the attackers realized what she was about and fired at her, leaving nothing behind but a single bullet hole in the tablecloth. The fort used the extra gunpowder to fire its one cannon, repelling the besiegers until reinforcements came. Their arrived caused the attacking force to remove itself from the area.

While it’s perfectly plausible and likely that that Elizabeth retrieved gunpowder from Zane’s house, many of the incident’s details are likely as fictious as those found in Betty Zane, the novel about the attack on the fort written by Betty’s great-grandnephew, Zane Grey. If she could carry a twenty-five keg of powder, then it made far more sense to leave it in that rather than put it into a tablecloth converted into a makeshift bag. It’s inevitable the powder would fall out between spaces where the cloth didn’t come together tightly. Also, a tablecloth made for a bigger target and a couple of shots through it would have really made it leak.

The attack on Fort Henry is often cited as the last battle of the American Revolution. It was not. The very last fight between the Patriots and Redcoats on American soil was the Battle of Dills Bluff in South Carolina on November 14, 1782. It was an unsuccessful American attack against the British to prompt them to depart.

With the war over, Ebenezer Zane gained a proper claim to the land he had squatted upon. In 1790 he, or more likely his wife, Elizabeth, established the first nursery in the Upper Ohio Valley where a new species of fruit, Zane’s Greening, was developed. This variety of apple was once popular in eastern Ohio, but if it’s still available, it likely uses another name. I was unable to find any reference to it past 1903.

In 1788 Zane became a member of the Virginia Federal Commission, the body that ultimately decided Virginia would ratify the U.S. Constitution. Around this time, and exact dates are hard to pin down, Zane’s daughter Sara fell in love with John McIntire. Sources vary as to their ages but one of the more reliable ones says she was fourteen and he twenty-nine when they met, and that she was fifteen when they married. Since she was born on February 22, 1773, this means her wedding was in 1787 or 1788. Her father and mother both objected to the nuptials, but there was no stopping them. On the day of the wedding, a sulking Ebenezer departed on a hunting trip while Elizabeth struck Sarah with her shoe.

John McIntire was born in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1759. Either of Scottish or Irish descent (and possibly a mix of both), one of his legs was shorter than the other. This coupled with little formal education limited his career options. He took up the trade of traveling shoemaker, this profession being what brought him to Wheeling. Here he worked for a merchant with whom he later became a partner. For a time he and Sarah moved to farm but a problematic deed forced them to return to Wheeling.

At this time the Zane family lived along the eastern border of what was then known as the Northwest Territory from which the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin were carved. It had been granted to the United States by the Treaty of Paris, which formally ended the American Revolution. Despite this concession, the British didn’t remove their military outposts from the territory and it was from these they encouraged Native Americans in the region to attack pioneers to discourage further settlement.

The British didn’t have to work very hard to accomplish this. Realizing an influx of settlers would displace them from their land, the Myaamia (Miami), Leni-Lenape (Delaware), Shawnee, Ottawa and Objibwa formed the Northwest Confederacy to stop this encroachment. President George Washington, ever the land speculator, was having none of this, so twice he sent ill-disciplined, barely trained and poorly equipped militias to deal with them. When these expeditions failed miserably, he sent Revolutionary War veteran General Anthony Wayne to deal with the Confederacy. This he did, handing it its defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers.

After this, Confederacy representatives made their way to Fort Greene Ville for treaty negotiations. One of those present was Isaac Zane, Ebenezer’s youngest brother whose path in life diverged greatly from the rest of his family. In 1762 at the age of nine, he and his eleven-year-old brother, Jonathan, were kidnapped by Wyandots. Two years later Jonathan was ransomed and returned to his family, but Wyandot chief Tarhee adopted Isaac as his own son. For the next nine years Isaac lived with the chief and his daughter, Myeerah, who was four when Isaac arrived. Her mother was a French-Canadian who had been captured by the Wyandots and decided to remain with them when freedom was offered.

The attack on Fort Henry is often cited as the last battle of the American Revolution. It was not. The very last fight between the Patriots and Redcoats on American soil was the Battle of Dills Bluff in South Carolina on November 14, 1782. It was an unsuccessful American attack against the British to prompt them to depart.

With the war over, Ebenezer Zane gained a proper claim to the land he had squatted upon. In 1790 he, or more likely his wife, Elizabeth, established the first nursery in the Upper Ohio Valley where a new species of fruit, Zane’s Greening, was developed. This variety of apple was once popular in eastern Ohio, but if it’s still available, it likely uses another name. I was unable to find any reference to it past 1903.

In 1788 Zane became a member of the Virginia Federal Commission, the body that ultimately decided Virginia would ratify the U.S. Constitution. Around this time, and exact dates are hard to pin down, Zane’s daughter Sara fell in love with John McIntire. Sources vary as to their ages but one of the more reliable ones says she was fourteen and he twenty-nine when they met, and that she was fifteen when they married. Since she was born on February 22, 1773, this means her wedding was in 1787 or 1788. Her father and mother both objected to the nuptials, but there was no stopping them. On the day of the wedding, a sulking Ebenezer departed on a hunting trip while Elizabeth struck Sarah with her shoe.

John McIntire was born in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1759. Either of Scottish or Irish descent (and possibly a mix of both), one of his legs was shorter than the other. This coupled with little formal education limited his career options. He took up the trade of traveling shoemaker, this profession being what brought him to Wheeling. Here he worked for a merchant with whom he later became a partner. For a time he and Sarah moved to farm but a problematic deed forced them to return to Wheeling.

At this time the Zane family lived along the eastern border of what was then known as the Northwest Territory from which the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin were carved. It had been granted to the United States by the Treaty of Paris, which formally ended the American Revolution. Despite this concession, the British didn’t remove their military outposts from the territory and it was from these they encouraged Native Americans in the region to attack pioneers to discourage further settlement.

The British didn’t have to work very hard to accomplish this. Realizing an influx of settlers would displace them from their land, the Myaamia (Miami), Leni-Lenape (Delaware), Shawnee, Ottawa and Objibwa formed the Northwest Confederacy to stop this encroachment. President George Washington, ever the land speculator, was having none of this, so twice he sent ill-disciplined, barely trained and poorly equipped militias to deal with them. When these expeditions failed miserably, he sent Revolutionary War veteran General Anthony Wayne to deal with the Confederacy. This he did, handing it its defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers.

After this, Confederacy representatives made their way to Fort Greene Ville for treaty negotiations. One of those present was Isaac Zane, Ebenezer’s youngest brother whose path in life diverged greatly from the rest of his family. In 1762 at the age of nine, he and his eleven-year-old brother, Jonathan, were kidnapped by Wyandots. Two years later Jonathan was ransomed and returned to his family, but Wyandot chief Tarhee adopted Isaac as his own son. For the next nine years Isaac lived with the chief and his daughter, Myeerah, who was four when Isaac arrived. Her mother was a French-Canadian who had been captured by the Wyandots and decided to remain with them when freedom was offered.

In 1772 Isaac returned to his childhood home only to find most of his brothers and sisters had left. Embracing colonial society in full, from 1773 to 1775 he served in the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1777 he returned to the Wyandots and around this time married Myeerah. She bore him four daughters and three sons. The two remained together until Isaac’s death in 1816 at the age of sixty-three. Isaac, a noted athlete, was well regarded by both Native Americans and whites. For his service during the treaty negotiations, the U.S. government gave him land near the headwaters of the Mad River. He built a home in what is now Zanesfield (not to be confused with Zanesville) and became close friends with his neighbor Simon Kenton, about whom I wrote another article that can be read here.

The Treaty of Greenville, signed about a year after the Battle of Fallen Timbers, forced members of the Confederacy to cede much of their land, most of it in what would become part of the State of Ohio. It also compelled the British to remove their military outposts by July 1, 1796. With peace settled, Ebenezer petitioned Congress to grant him permission to build a road from Wheeling to Limestone, Kentucky, which is now Maysville. Zane pledged to pay for it himself with the caveat that he wanted a few sections of land along the route granted to him. Specifically he wanted land on both sides of the Muskingum, Scioto and Hockhocking (now Hocking) Rivers so he could establish ferries.

Congress approved the proposal in May 1896. Now Zane had to plot and survey the route. He tasked his brothers Jonathan and Silas as well as a Native American named Tomepomehaia to do this. The brothers had explored up and down the Ohio River in 1771, and Jonathan knew the area well, experience gained when he served as a guide and spy during Lord Dunmore’s War and the American Revolution. The three surveyors more or less followed an existing Native American trail, which is why the road became known as Zane’s Trace, although in its earliest days it was known as Zane’s road.

Ebenezer put Jonathan and John McIntire in charge of the actual road construction. By this point Ebenezer had not only reconciled himself that McIntire was his son-in-law, he had come to rely upon him. The work party included William McCulloch, Ebenezer Ryan and John Green. Green was responsible for the pack horse that carried the tents and other supplies. His duties also included hunting for game and cooking. One source says that during the road’s construction, McIntire may have shot himself in the right hand while loading his gun, crippling him for life. Another story says he did this while defending Fort Henry during the 1782 attack upon it.

The Treaty of Greenville, signed about a year after the Battle of Fallen Timbers, forced members of the Confederacy to cede much of their land, most of it in what would become part of the State of Ohio. It also compelled the British to remove their military outposts by July 1, 1796. With peace settled, Ebenezer petitioned Congress to grant him permission to build a road from Wheeling to Limestone, Kentucky, which is now Maysville. Zane pledged to pay for it himself with the caveat that he wanted a few sections of land along the route granted to him. Specifically he wanted land on both sides of the Muskingum, Scioto and Hockhocking (now Hocking) Rivers so he could establish ferries.

Congress approved the proposal in May 1896. Now Zane had to plot and survey the route. He tasked his brothers Jonathan and Silas as well as a Native American named Tomepomehaia to do this. The brothers had explored up and down the Ohio River in 1771, and Jonathan knew the area well, experience gained when he served as a guide and spy during Lord Dunmore’s War and the American Revolution. The three surveyors more or less followed an existing Native American trail, which is why the road became known as Zane’s Trace, although in its earliest days it was known as Zane’s road.

Ebenezer put Jonathan and John McIntire in charge of the actual road construction. By this point Ebenezer had not only reconciled himself that McIntire was his son-in-law, he had come to rely upon him. The work party included William McCulloch, Ebenezer Ryan and John Green. Green was responsible for the pack horse that carried the tents and other supplies. His duties also included hunting for game and cooking. One source says that during the road’s construction, McIntire may have shot himself in the right hand while loading his gun, crippling him for life. Another story says he did this while defending Fort Henry during the 1782 attack upon it.

Roadwork mainly consisted of cutting down trees to make it wide enough for a horse to walk, although in wet areas corduroys—logs laid in front of one another—put down. The road was completed in the summer of 1797. Being the only route from east to west through Ohio for some years, a flood of immigrants passed over it, their trampling about having the effect of widening it. Those who used it didn’t do so for free. They paid to be ferried across rivers and, later, to cross toll bridges.

Along the road grew up New Lancaster (now just Lancaster), Circleville, Chillicothe, Bainbridge, and West Union. Of those, New Lancaster was founded along the Hockhocking River and laid out by Zane’s sons. Here Dudley Woodbridge started a store that was once burgled. An ad in the March 26, 1801, edition of the Scioto Gazette offered a reward for the return of a variety of stolen merchandise including several colors of good cloth, muslin, and silk stockings. Also taken were $10 and $30 bank notes issued by a Baltimore bank.

For their work on his road, Ebenezer rewarded Jonathan and McIntire his plot of land along the Muskingum River. In the autumn of 1799 McIntire and his wife, Sarah, settled here. Jonathan Zane and McIntire formally laid out the town that would become Zanesville on April 28, 1802. With the road being useless if travelers couldn’t cross the river here, McIntire started a ferry service at the place where the town’s famous Y bridge is found. At first he attempted to charge passing boats a toll, too, but this he soon abandoned, probably because the notoriously rough rivermen refused to pay it. Later he replaced the ferry with a toll bridge.

He built himself a double log cabin that served as an inn. It stood on the corner of what are now 2nd and Market Streets. The inn’s most famous guest was probably Louis-Philippe. At the time of his visit he was just another exiled nobleman from Napoleonic France, but much later he became France’s very last king. (Napoleon III, who reigned later, was a self-declared emperor.) McIntire had a reputation as a good host. His wife, Sarah, was a renowned hostess.

Unable to bear children, over her lifetime Sarah adopted twelve children, including Amelia, McIntire’s illegitimate daughter he had fathered with Sarah’s cousin, Lyddy. McIntire died on July 29, 1815, at the age of fifty-six. Amelia, then fifteen, died five years later of an unspecified health issue. In 1816 Sarah married Methodist minister Reverend David Young. she built two Methodist churches in town with her own funds. McIntire’s will stipulated that after Sarah’s death, if Amelia produced no heirs, his estate was to be used to construct a school for the poor. These funds paid for the construction of John McIntire Children’s Home. In it hung portraits of him and Sarah. The school was torn down in 1944.

Both Jonathan and Ebenezer remained in Wheeling until their deaths. Ever the land speculator and pioneer, in 1806 Ebenezer planned the town of Bridgeport across the Ohio River from Wheeling on land he gave to one of his brothers. He was an important Ohio pioneer by proxy. He died of jaundice at the age of sixty-four on November 12, 1812.🕜

Along the road grew up New Lancaster (now just Lancaster), Circleville, Chillicothe, Bainbridge, and West Union. Of those, New Lancaster was founded along the Hockhocking River and laid out by Zane’s sons. Here Dudley Woodbridge started a store that was once burgled. An ad in the March 26, 1801, edition of the Scioto Gazette offered a reward for the return of a variety of stolen merchandise including several colors of good cloth, muslin, and silk stockings. Also taken were $10 and $30 bank notes issued by a Baltimore bank.

For their work on his road, Ebenezer rewarded Jonathan and McIntire his plot of land along the Muskingum River. In the autumn of 1799 McIntire and his wife, Sarah, settled here. Jonathan Zane and McIntire formally laid out the town that would become Zanesville on April 28, 1802. With the road being useless if travelers couldn’t cross the river here, McIntire started a ferry service at the place where the town’s famous Y bridge is found. At first he attempted to charge passing boats a toll, too, but this he soon abandoned, probably because the notoriously rough rivermen refused to pay it. Later he replaced the ferry with a toll bridge.

He built himself a double log cabin that served as an inn. It stood on the corner of what are now 2nd and Market Streets. The inn’s most famous guest was probably Louis-Philippe. At the time of his visit he was just another exiled nobleman from Napoleonic France, but much later he became France’s very last king. (Napoleon III, who reigned later, was a self-declared emperor.) McIntire had a reputation as a good host. His wife, Sarah, was a renowned hostess.

Unable to bear children, over her lifetime Sarah adopted twelve children, including Amelia, McIntire’s illegitimate daughter he had fathered with Sarah’s cousin, Lyddy. McIntire died on July 29, 1815, at the age of fifty-six. Amelia, then fifteen, died five years later of an unspecified health issue. In 1816 Sarah married Methodist minister Reverend David Young. she built two Methodist churches in town with her own funds. McIntire’s will stipulated that after Sarah’s death, if Amelia produced no heirs, his estate was to be used to construct a school for the poor. These funds paid for the construction of John McIntire Children’s Home. In it hung portraits of him and Sarah. The school was torn down in 1944.

Both Jonathan and Ebenezer remained in Wheeling until their deaths. Ever the land speculator and pioneer, in 1806 Ebenezer planned the town of Bridgeport across the Ohio River from Wheeling on land he gave to one of his brothers. He was an important Ohio pioneer by proxy. He died of jaundice at the age of sixty-four on November 12, 1812.🕜