Invention of Pampers

INVENTION OF PAMPERS

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

Boater ad. Arizona Post (Tucson), January 5, 1951.

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

Historically, people across the world dealt with babies relieving themselves in different ways. In many warm African nations, babies and children not yet potty trained were left naked and went when and where the need struck. In China, mother of infants put them over a container or over the street. Once babies learned to walk, they were given underpants or shorts with strategically placed slits. In America, the Inuit fitted their babies with moss held in place by sealskin. Other Native Americans used rabbit skin diapers with grass as the absorbent.

Medieval Europeans swaddled their babies in strips of cloth or linen that could be left in place for up to three days despite the mess it made. Babies who learned to walk were fitted with blouses or small dresses that reached the ground with nothing hindering the infant’s bottom to allow what it released to fall under unhindered to the ground. Ashes were thrown onto excrement to make it easier to sweep up. Urine-soaked swaddling wasn’t cleaned but instead just held in front of a fire to dry because people thought urine was a disinfectant and was thus good for the infant. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, baby bottoms were wiped without soap and water. Small wonder the infant mortality rate was so high.

Swaddling was replaced by diapers partly because during the Industrial Revolution more people could afford mass produced furniture and didn’t want it ruined by their babies’ waste. Babies in the United States were fitted with triangle-shaped diapers held together with straight pins, which were largely replaced by the safety pin after it was invented by Walter Hunt of New York in 1849. Diapers were covered with a pant called a “pilch” or “soaker” made of tightly woven wool. Rubber pants came into use in the 1890s, but these often caused diaper rash. One estimate proposed about 25 percent of all children suffered from this condition, some getting it so bad they needed hospitalization. Diaper rash was sometimes treated using powered sulfur or browned flour, remedies still recommended by online forums to this day.

Medieval Europeans swaddled their babies in strips of cloth or linen that could be left in place for up to three days despite the mess it made. Babies who learned to walk were fitted with blouses or small dresses that reached the ground with nothing hindering the infant’s bottom to allow what it released to fall under unhindered to the ground. Ashes were thrown onto excrement to make it easier to sweep up. Urine-soaked swaddling wasn’t cleaned but instead just held in front of a fire to dry because people thought urine was a disinfectant and was thus good for the infant. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, baby bottoms were wiped without soap and water. Small wonder the infant mortality rate was so high.

Swaddling was replaced by diapers partly because during the Industrial Revolution more people could afford mass produced furniture and didn’t want it ruined by their babies’ waste. Babies in the United States were fitted with triangle-shaped diapers held together with straight pins, which were largely replaced by the safety pin after it was invented by Walter Hunt of New York in 1849. Diapers were covered with a pant called a “pilch” or “soaker” made of tightly woven wool. Rubber pants came into use in the 1890s, but these often caused diaper rash. One estimate proposed about 25 percent of all children suffered from this condition, some getting it so bad they needed hospitalization. Diaper rash was sometimes treated using powered sulfur or browned flour, remedies still recommended by online forums to this day.

Betsy Wetsy Doll Ad

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

In the days before disposable diapers, cloth ones had to be folded like here from this 1937 photo. Harris & Ewing.

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

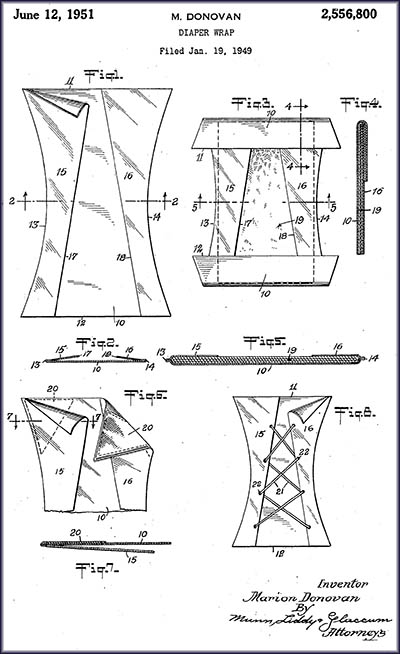

Marion Donavan's Patent for a Disposable Diaper

Pampers Today

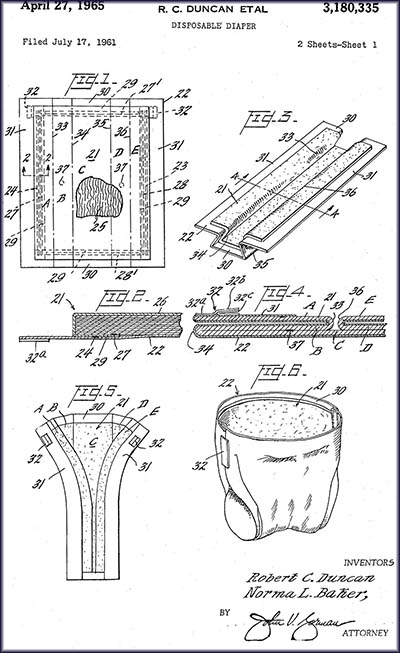

Pampers Patent

The idea of leaving diapers on for days at a time was being challenged in nineteenth and early twentieth century America by medical professions. In his 1839 book The Young Mother or Management of Children in Regard to Health, as an example, William A. Alcott wrote: “On the subject of changing the wet clothing of a child, there is a strange and monstrous error abroad; which is, that by suffering them to remain wet and cold, we harden the constitution. The filthiness of this practice is enough to condemn it, were there nothing else to be said against it.”

Doctor William P. Dewees wrote in his 1847 book A Treatise on Physical and Medical of Children that “upon this subject [of changing diapers], there should be but one opinion; and this should become a maxim, from which there should be no departure; namely, that the child should never be long wet, or dirty, at a time.” Doctor George D. Lyman’s 1915 book Care & Feeding of the Infant recommended diapers be made out of old linen. New material needed to be “boiled for fifteen minutes” and washed. Flannel and wool were not to be used as diapers because they were both too warm and didn’t allow the “the evaporation of moisture.” Soiled diapers needed to be boiled for 15 minutes.

Doctor William P. Dewees wrote in his 1847 book A Treatise on Physical and Medical of Children that “upon this subject [of changing diapers], there should be but one opinion; and this should become a maxim, from which there should be no departure; namely, that the child should never be long wet, or dirty, at a time.” Doctor George D. Lyman’s 1915 book Care & Feeding of the Infant recommended diapers be made out of old linen. New material needed to be “boiled for fifteen minutes” and washed. Flannel and wool were not to be used as diapers because they were both too warm and didn’t allow the “the evaporation of moisture.” Soiled diapers needed to be boiled for 15 minutes.

During World War II, hundreds of thousands of mothers with children not yet potty trained went to work. After work most had neither the time nor energy to wash dirty diapers when they got home, so they turned to washing services. Before the United States entered the war in early 1941, Johnson & Johnson introduced a new disposable diaper branded as Chux. Fabricated out of Masslinn, a cotton that was, according to a 1942 Time article, “made without a spindle or a loom,” Chux didn’t stay on the market for long. Johnson & Johnson pulled it from the shelves so it could uses its supply of Masslinn to produced materiel for the military. Though it did American women no good, in 1942 company Paulistróm introduced one made out of cellulose in Sweden that was held on with rubber pants.

The next step in the quest for a better diaper came from the mind of Marion O’Brien, who was born in South Bend, Indiana, on October 15, 1917. At the age of seven her mother died. Her father, Miles O’Brien, was an engineer who graduated from Perdue University. He and his identical twin brother, Richard, started and ran the South Bend Lathe Works factory. After Miles’s wife died, he frequently took his daughter to work and encouraged her to solve problems. She invented a new kind of tooth powder while still in elementary school.

The next step in the quest for a better diaper came from the mind of Marion O’Brien, who was born in South Bend, Indiana, on October 15, 1917. At the age of seven her mother died. Her father, Miles O’Brien, was an engineer who graduated from Perdue University. He and his identical twin brother, Richard, started and ran the South Bend Lathe Works factory. After Miles’s wife died, he frequently took his daughter to work and encouraged her to solve problems. She invented a new kind of tooth powder while still in elementary school.

Graduating from Rosemont College near Philadelphia in 1939, she took a job in New York at Vogue as an assistant beauty editor. Upon marrying leather importer James Donovan, she moved to Westport, Connecticut, where the two started a family. In 1946 she had a daughter, her second child, who unfailingly wet herself after being put down for nap, leaving both her clothes and mattress soaked. Marion didn’t like to use rubber pants because they caused diaper rash, so one day she cut part of her shower curtain out and sewed it into a shape into which a diaper could be put. Being less tight fitting than rubber pants allowed air to get in and kept the wet from seeping out.

Donovan tried to sell her diaper wrap but no company was interested, so in 1949 she went into business for herself. Made out of parachute cloth and secured with snaps rather than safety pins, she called it the Boater. It debuted in 1949. It initially sold it at Saks Fifth Avenue in New York City and was an instant success. Two years later, Mrs. Donovan sold her company to the Keko Corporation for $1 million.

Donovan tried to sell her diaper wrap but no company was interested, so in 1949 she went into business for herself. Made out of parachute cloth and secured with snaps rather than safety pins, she called it the Boater. It debuted in 1949. It initially sold it at Saks Fifth Avenue in New York City and was an instant success. Two years later, Mrs. Donovan sold her company to the Keko Corporation for $1 million.

Next, she put her efforts into creating a disposable diaper made out of paper. The first problem she had to overcome was getting the pee to wick away from the baby’s skin rather than just absorb it. This she achieved by creating the diaper in layers. Her business success granted her access to executives at paper companies, but they laughed at her idea, and it never sold. Despite this failure, over her lifetime she was granted 20 patents. At the age of 41, she earned a degree in architecture and designed her own house.

In the mid-1950s, Victor Mills, a chemical engineer at Procter & Gamble, was disenchanted with changing his grandchildren’s diapers, so he came up with the idea of creating disposable ones. The difference between him and Donovan was that he was in the position to get a large American company to sell his creation. Mills joined P&G in 1926 and was the man behind an improved process to make Ivory Soap. Born on March 28, 1897, in Milford, Nebraska, he served in the U.S. Navy during World War I and afterwards worked as welder in Hawaii. Here he met and married his first wife, Grace Riggs, and soon after attended University of Washington.

In the mid-1950s, Victor Mills, a chemical engineer at Procter & Gamble, was disenchanted with changing his grandchildren’s diapers, so he came up with the idea of creating disposable ones. The difference between him and Donovan was that he was in the position to get a large American company to sell his creation. Mills joined P&G in 1926 and was the man behind an improved process to make Ivory Soap. Born on March 28, 1897, in Milford, Nebraska, he served in the U.S. Navy during World War I and afterwards worked as welder in Hawaii. Here he met and married his first wife, Grace Riggs, and soon after attended University of Washington.

Mills had a hand in developing or improving a number of P&G products. He figured out how to keep the oil from separating in Jif peanut butter, came up with a way to produce Pringles, and got rid of the lumps from Duncan Hines cake mixes by using the same machine that milled fine soap flakes. His daughter, Maile Mills Cuddy, recalled that her father often brought products home for testing: “We would taste cakes until they came out of our ears.” She remembered trying a cherry red liquid tooth cleaner called Teel that tasted good but didn’t work.

When Mills put his mind to creating a better diaper, he decided upon a disposable one made of layered paper similar to what Marion Donovan had come up with. He took the idea to his bosses at P&G and headed the development team to make it, although his name didn’t appear on the patent. The first thing Mills’ team did was go out and buy a Betsy Wetsy, a popular doll that wet itself when given water through its mouth. The initial diaper prototype consisted of a rectangular pads made of tissue paper lined with rayon and sealed with polyethylene.

Mills tested the prototype on a granddaughter while driving her and her siblings home from a vacation in Maine. In 1959, 37,000 prototypes were hand sewn for sale in Rochester, New York. The first commercial version debuted in Peoria, Illinois, in the same year that Mills retired: 1961. It wasn’t an immediate hit. Parents balked at its high cost of 10 cents a diaper and disliked that fact it had to be secured with safety pins. They resembled a thick pair of underwear.

When Pampers’ price came down to 6 cents a piece, sales increased significantly. Later versions came with tape to replace the need for safety pins. In 1967, a less bulky hourglass-shaped version that fitted better was patented. The year before, Johnson & Johnson’s Frank Carlyle Harmon and Dow Chemical’s Billy Gene Harper filed a patent for superabsorbent polymers that could absorb up to 300 times their weight in water. This material replaced the paper in Pampers, making them much thinner. By the 1980s, disposable diapers became the target of environmentalists worrying they’d fill up landfills, but a study run by Federal environmental researchers found this was still better than washing cloth ones. Pediatricians praised disposable diapers because they reduced diaper rash.🕜

When Mills put his mind to creating a better diaper, he decided upon a disposable one made of layered paper similar to what Marion Donovan had come up with. He took the idea to his bosses at P&G and headed the development team to make it, although his name didn’t appear on the patent. The first thing Mills’ team did was go out and buy a Betsy Wetsy, a popular doll that wet itself when given water through its mouth. The initial diaper prototype consisted of a rectangular pads made of tissue paper lined with rayon and sealed with polyethylene.

Mills tested the prototype on a granddaughter while driving her and her siblings home from a vacation in Maine. In 1959, 37,000 prototypes were hand sewn for sale in Rochester, New York. The first commercial version debuted in Peoria, Illinois, in the same year that Mills retired: 1961. It wasn’t an immediate hit. Parents balked at its high cost of 10 cents a diaper and disliked that fact it had to be secured with safety pins. They resembled a thick pair of underwear.

When Pampers’ price came down to 6 cents a piece, sales increased significantly. Later versions came with tape to replace the need for safety pins. In 1967, a less bulky hourglass-shaped version that fitted better was patented. The year before, Johnson & Johnson’s Frank Carlyle Harmon and Dow Chemical’s Billy Gene Harper filed a patent for superabsorbent polymers that could absorb up to 300 times their weight in water. This material replaced the paper in Pampers, making them much thinner. By the 1980s, disposable diapers became the target of environmentalists worrying they’d fill up landfills, but a study run by Federal environmental researchers found this was still better than washing cloth ones. Pediatricians praised disposable diapers because they reduced diaper rash.🕜