INVENTION OF THE ALLIGATOR CLIP

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

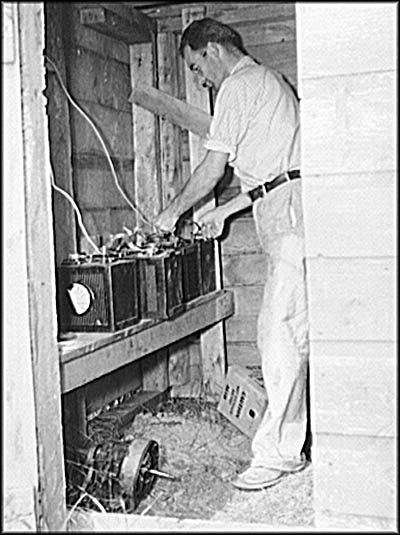

Connecting Automobile Batteries with Alligator Clips

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

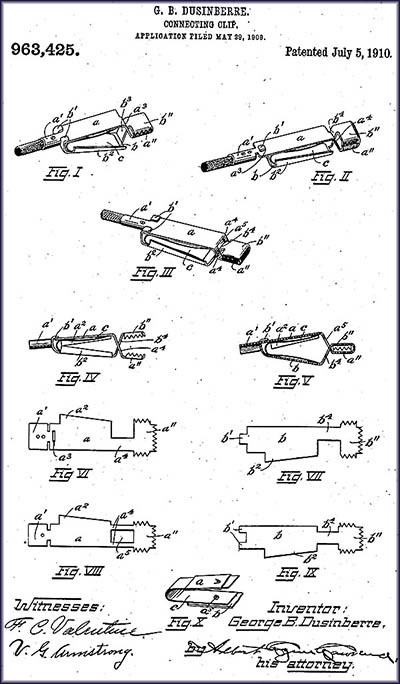

George Dusinberre Patent for His Improved Alligator Clip

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

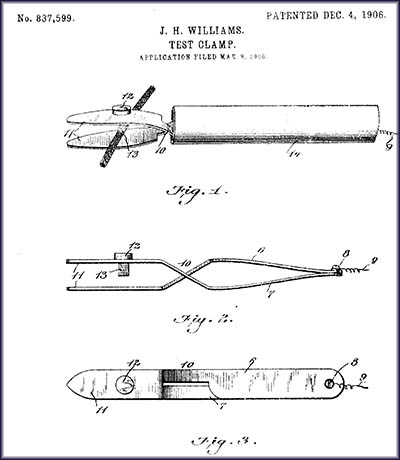

John H. William's Patent for a Test Clip

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

You know that clip that holds your bib on at the dentist? It’s made by the Mueller Electric Company. Founded in 1908 by Ralph S. Mueller, it makes a variety of alligator clips for all sorts of purposes. Its website proudly reports that Ralph Mueller invented the alligator clip, a claim also made in his obituary in Cleveland’s Plain Dealer. He did no such thing, though it’s hard to say if it would’ve become such a success without him.

Born in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in April 1877, Mueller was the son of storekeeper. In 1894 he began attending the University of Nebraska because it had the lowest tuition of those colleges to which he’d been accepted. While there he became the school’s middle weight boxing champion. In his sophomore year he considered getting into the field of medicine but didn’t think he’d be able to afford medical school. He studied electrical engineering instead. Upon reflection years later, he figured he’d have made a good surgeon.

After earning his Bachelor of Science, he spent another year at the school working towards his master’s degree, but a bad professor prompted him to quit. He moved to Chicago where he went to work for the Western Electric Company. In his autobiography, he made himself a member of the self-made man club by pointing out he’d arrived in the city with nothing more than a small trunk, a suit case and his violin. Never mind that most college graduates possess little in the way of money or personal stuff.

Born in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in April 1877, Mueller was the son of storekeeper. In 1894 he began attending the University of Nebraska because it had the lowest tuition of those colleges to which he’d been accepted. While there he became the school’s middle weight boxing champion. In his sophomore year he considered getting into the field of medicine but didn’t think he’d be able to afford medical school. He studied electrical engineering instead. Upon reflection years later, he figured he’d have made a good surgeon.

After earning his Bachelor of Science, he spent another year at the school working towards his master’s degree, but a bad professor prompted him to quit. He moved to Chicago where he went to work for the Western Electric Company. In his autobiography, he made himself a member of the self-made man club by pointing out he’d arrived in the city with nothing more than a small trunk, a suit case and his violin. Never mind that most college graduates possess little in the way of money or personal stuff.

Alligator Clip

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Jumper Cable

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

At Western Electric he worked in the Telephone Switch Assembly Department fusing interior telephone cables using dry cotton tape. Determined to learn everything he could, he would sneak blueprints out at night to study them. So instead of slowly accumulating the knowledge over several years that a worker would normally gain in the department, Urry learned it at an accelerated pace. In 1900, he left the company to become a traveling salesman selling incandescent light bulbs for the Sawyer-Mann Company, a subsidiary of Westinghouse.

In the fall of 1902, he returned to the telephone industry, this time going to work for the Kellogg Switchboard and Supply Company in Chicago as a sales engineer and traveling salesman. His primary territory was Michigan. In 1904, Kellogg asked Mueller to replace a man working out of the Cleveland branch who’d been fired for padding his expenses. To this Mueller agreed so long as he was guaranteed to be left posted in Cleveland for the next two years. He wanted stability for him and his very pregnant wife. Between 1904 and 1908 he traveled extensively and sold more than any other engineer. Small wonder he was greatly upset and even considered quitting after being passed over for a promotion.

Mueller worked in a building where many different businesses had offices, allowing him to get to know people outside of Kellogg. In 1906, John H. Williams of the Cuyahoga Telephone Company showed Mueller his new invention: a light bulb with a wire attached. At the wire’s other end was placed a clip with needles protruding from it that would bite into a live electric wire to allow plumbers to tap into power source so they could shine light into the dark places they often worked. Most of the clip was inside a rubber tube that served as insultation. Williams asked Mueller if he’d be interested in starting a company to sell this product. He was.

Partners were needed to capitalize it, and Mueller knew people who might be willing to invest. He approached W.L. Carey, secretary of the United States Phone Company whose office was in the same building as his. He also caught the interest of a Mr. Case, who operated a fishing fleet in Lake Erie, and insurance seller Fred P. Thomas. These five each contributed $200 and incorporated the venture as the Williams Test Clamp Company. Thomas served as president, Mueller as vice-president, Carey as the secretary-treasurer, and Williams as the general manager.

In the fall of 1902, he returned to the telephone industry, this time going to work for the Kellogg Switchboard and Supply Company in Chicago as a sales engineer and traveling salesman. His primary territory was Michigan. In 1904, Kellogg asked Mueller to replace a man working out of the Cleveland branch who’d been fired for padding his expenses. To this Mueller agreed so long as he was guaranteed to be left posted in Cleveland for the next two years. He wanted stability for him and his very pregnant wife. Between 1904 and 1908 he traveled extensively and sold more than any other engineer. Small wonder he was greatly upset and even considered quitting after being passed over for a promotion.

Mueller worked in a building where many different businesses had offices, allowing him to get to know people outside of Kellogg. In 1906, John H. Williams of the Cuyahoga Telephone Company showed Mueller his new invention: a light bulb with a wire attached. At the wire’s other end was placed a clip with needles protruding from it that would bite into a live electric wire to allow plumbers to tap into power source so they could shine light into the dark places they often worked. Most of the clip was inside a rubber tube that served as insultation. Williams asked Mueller if he’d be interested in starting a company to sell this product. He was.

Partners were needed to capitalize it, and Mueller knew people who might be willing to invest. He approached W.L. Carey, secretary of the United States Phone Company whose office was in the same building as his. He also caught the interest of a Mr. Case, who operated a fishing fleet in Lake Erie, and insurance seller Fred P. Thomas. These five each contributed $200 and incorporated the venture as the Williams Test Clamp Company. Thomas served as president, Mueller as vice-president, Carey as the secretary-treasurer, and Williams as the general manager.

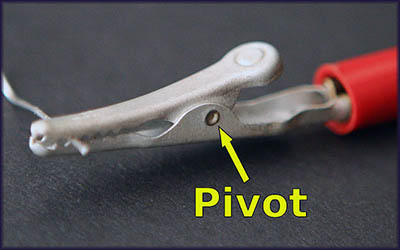

It didn’t take long before Mueller realized the clip Williams had invented was too expensive to produce. One day George Dusinberre saw Mueller trying to come up with an improvement. Dusinberre cut up a couple business cards and created a model of a clip with two jaws on a pivot that could clamp down onto objects. Instead of needles, it had a pair of serrated jaws with a U-shaped spring. Mueller took the idea to the others in the company, but Williams violently opposed any change to his invention. The board declined to adopt it, so the next day Mueller allowed Williams to buy him out.

Mueller suggested to Dusinberre that they put his new clip onto the market. He agreed and offered to put Mueller’s name on the patent application as co-inventor, but Mueller declined because it wasn’t his idea. This he later regretted. Dusinberre paid for the patent application himself. He and Mueller formed a partnership called R.S. Mueller & Company. Mueller’s task was to oversee the new clip’s manufacture as well as its sales. The rights to Dusinberre’s patent were transferred to his and Urry’s business.

The company’s first clips were made of steel and coated with zinc, but they became easily dirty, so the coating was changed to nickel plating. They were made first by Cleveland’s Otto Konigslow Company, then the Cleveland Metal Stamping Company. R.S. Mueller took over manufacturing them itself in its factory, which was built in 1922 on Cleveland’s East Street. Now on the National Register for Historic Places, that factory has since been turned into lofts.

Mueller’s company found its success thanks to Charles Kettering’s invention of the electric self-starter for the automobile. Originally made for Cadillac, other automobile manufacturers also adopted Kettering’s invention. This created a need for something that could quickly connect storage batteries to a charger, so R.S. Mueller invented the jumper cable, and also created a smaller one for motorcycles. Dusinberre lost interest in the company and allowed Mueller to buy him out for $52,300. The company changed its name to Mueller Electric.

Mueller suggested to Dusinberre that they put his new clip onto the market. He agreed and offered to put Mueller’s name on the patent application as co-inventor, but Mueller declined because it wasn’t his idea. This he later regretted. Dusinberre paid for the patent application himself. He and Mueller formed a partnership called R.S. Mueller & Company. Mueller’s task was to oversee the new clip’s manufacture as well as its sales. The rights to Dusinberre’s patent were transferred to his and Urry’s business.

The company’s first clips were made of steel and coated with zinc, but they became easily dirty, so the coating was changed to nickel plating. They were made first by Cleveland’s Otto Konigslow Company, then the Cleveland Metal Stamping Company. R.S. Mueller took over manufacturing them itself in its factory, which was built in 1922 on Cleveland’s East Street. Now on the National Register for Historic Places, that factory has since been turned into lofts.

Mueller’s company found its success thanks to Charles Kettering’s invention of the electric self-starter for the automobile. Originally made for Cadillac, other automobile manufacturers also adopted Kettering’s invention. This created a need for something that could quickly connect storage batteries to a charger, so R.S. Mueller invented the jumper cable, and also created a smaller one for motorcycles. Dusinberre lost interest in the company and allowed Mueller to buy him out for $52,300. The company changed its name to Mueller Electric.

During World War II, the U.S. military needed alligator clips for a variety of purposes. Although many manufacturers had to retool to build something completely different for the war effort, the miliary needed the variety of alligator clips already produced by Muller Electric. This meant it just needed to ramp up production. Its clips served many needs. It made 122,000 clips used on life jackets by American sailors to attach a red-lensed flashlight used to signal rescuers. The company provided the Soviet Union with 250,000 jumper cables used in its mobile storage shops for machines and maintenance that serviced its trucks. During the war, the company made a staggering 41 million clips of different types.

Military uses of the alligator clip didn’t diminish after the war’s conclusion. In 1954, the magazine Flying Aviation reported that combat pilots had trouble strapping into their ejector seats correctly. The article noted that “the most common error made by all pilots was the positioning of the alligator oxygen hose clip which secures the upper end of the oxygen hose (seat half) in a position for easy mating with the oxygen hose from the mask.” Pilots were clipping it to the strap of their harness instead of clothing, and that was a bad idea. Doing it incorrectly made it hard for pilots to extricate themselves from their seat belt.

Mueller’s wife passed in 1965 at the same time he was fighting cancer. He lived on a fifth-floor apartment and was attended by a nurse, Irene Grey. On February 14, 1966, the 88-year-old Mueller asked her to get him a pair of gloves from the bedroom that he wanted to give her. When she returned, he was nowhere to be found. Walking down a hallway that led to a fire escape, she looked down and saw his body on the ground below. He’d left a note behind on his desk.🕜

Military uses of the alligator clip didn’t diminish after the war’s conclusion. In 1954, the magazine Flying Aviation reported that combat pilots had trouble strapping into their ejector seats correctly. The article noted that “the most common error made by all pilots was the positioning of the alligator oxygen hose clip which secures the upper end of the oxygen hose (seat half) in a position for easy mating with the oxygen hose from the mask.” Pilots were clipping it to the strap of their harness instead of clothing, and that was a bad idea. Doing it incorrectly made it hard for pilots to extricate themselves from their seat belt.

Mueller’s wife passed in 1965 at the same time he was fighting cancer. He lived on a fifth-floor apartment and was attended by a nurse, Irene Grey. On February 14, 1966, the 88-year-old Mueller asked her to get him a pair of gloves from the bedroom that he wanted to give her. When she returned, he was nowhere to be found. Walking down a hallway that led to a fire escape, she looked down and saw his body on the ground below. He’d left a note behind on his desk.🕜