Isaac Ludwig Mill

Isaac Ludwig Mill

Before mills, the primary way to make flour was a mortar and pestle.

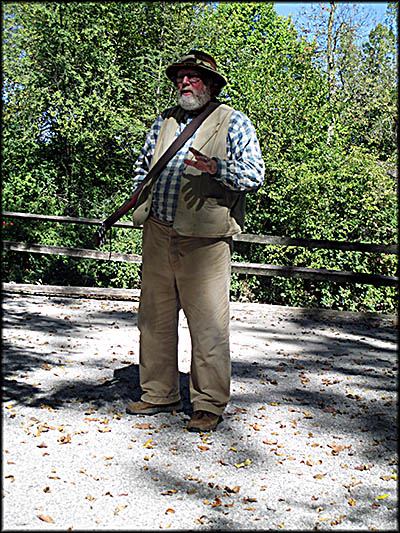

Canal boat crewman who sang a song for us.

Volunteer

On board theVolunteer

On the Canal

In the Lock

Approaching the Canal Lock

One the mules that towed the canal boat.

Lock Wicket

Small Steam Engine

Mill's Saw

Turbine

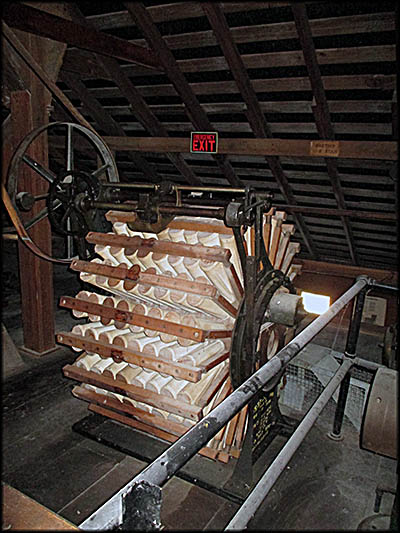

Mill's Dust Collector

I learned about the Isaac Ludwig Mill while visiting the Wolcott House in Maumee, Ohio. A tour guide there told me about it. She informed me that not only did the site offer a boat ride on a section of the Miami & Erie Canal, the boat went through a working lock. This I had to see.

The site is run by Metroparks Toledo even though it’s in Grand Rapids, Ohio, which is about thirty minutes south of the city of Toledo by car. It’s located at Kimble’s Landing, which is part of the Province Metropark. To confuse things even more, when the mill was constructed, the land upon which it now stands was part in town of Providence, most of which was destroyed by a fire in 1846 and finished off by a cholera epidemic in 1854. That a cholera broke out here isn’t surprising: it’s transmitted by contaminated water, and locals as well as canalboat passengers had a habit of drinking straight out of the canal.

The mill is free but the canal ride isn’t. The canalboat is Volunteer, and I recommend that during the peak summer months you buy tickets ahead of time for your ride so it’s not sold out when you get there. You start at an outdoor waiting area where a canalboat crewman tells you about the canal’s background. He warns you to remain in the covered part of the Volunteer when the boat is being turned around so you do get whacked on the head its water-soaked ropes. He also sang a canal song for us. The ride spans a distance of about one mile, and during the entire trip another guide gives a detailed background about the canal, life on it, and canalboats. Our guide, who was very good, gladly answered our questions.

The site is run by Metroparks Toledo even though it’s in Grand Rapids, Ohio, which is about thirty minutes south of the city of Toledo by car. It’s located at Kimble’s Landing, which is part of the Province Metropark. To confuse things even more, when the mill was constructed, the land upon which it now stands was part in town of Providence, most of which was destroyed by a fire in 1846 and finished off by a cholera epidemic in 1854. That a cholera broke out here isn’t surprising: it’s transmitted by contaminated water, and locals as well as canalboat passengers had a habit of drinking straight out of the canal.

The mill is free but the canal ride isn’t. The canalboat is Volunteer, and I recommend that during the peak summer months you buy tickets ahead of time for your ride so it’s not sold out when you get there. You start at an outdoor waiting area where a canalboat crewman tells you about the canal’s background. He warns you to remain in the covered part of the Volunteer when the boat is being turned around so you do get whacked on the head its water-soaked ropes. He also sang a canal song for us. The ride spans a distance of about one mile, and during the entire trip another guide gives a detailed background about the canal, life on it, and canalboats. Our guide, who was very good, gladly answered our questions.

The canal started out as the Erie & Wabash, which connected Toledo to Lafyette, Indiana. Upon being connected the Erie Canal, which went from Toledo the Cincinnati to connect Lake Erie with the Ohio River, the expanded system was renamed the Miami & Erie. Use of the section going to Layfette steadily declined starting in 1854 because of competition with railroads, and it fell into complete disuse in 1888. By 1850 many canals crisscrossed Ohio, and it’s these that made the state prosperous because it allowed farmers to ship their grain and industries to move their goods to Lake Erie or the Ohio River and from there to anywhere in the world.

Ohio’s canals were dug using just three tools: a shovel, a wood scoop to get the soil out, and a wheelbarrow for moving it elsewhere. Mostly Irish and German immigrants did the digging for 30 cents and a jigger (a shot) of whiskey a day. Malaria and cholera killed many. It’s said that four canal workers died per mile and may even be buried under the towpath.

Despite the fact that the Miami & Ohio Canal was cut through the western part of Ohio which seems rather flat in its northwestern section, elevations nonetheless vary considerably. The solution to this was to construct 103 locks in which water levels rose or dropped an average of three feet. This was accomplished by the opening and closing of wickets, or iron gates. The lock that Volunteer goes through is number 44. Upon entering it, you will see that the doors in front of you, called whalers, are closed. The canalboat’s crew then closes the ones behind you and in about ten minutes the water level rises roughly three feet. We were warned that this process can make some seasick, and during the years of the canal’s operation, passengers so afflicted usually got off the boat before it entering the lock, then got back on after it exited. No one the day I went lost their lunch.

Ohio’s canals were dug using just three tools: a shovel, a wood scoop to get the soil out, and a wheelbarrow for moving it elsewhere. Mostly Irish and German immigrants did the digging for 30 cents and a jigger (a shot) of whiskey a day. Malaria and cholera killed many. It’s said that four canal workers died per mile and may even be buried under the towpath.

Despite the fact that the Miami & Ohio Canal was cut through the western part of Ohio which seems rather flat in its northwestern section, elevations nonetheless vary considerably. The solution to this was to construct 103 locks in which water levels rose or dropped an average of three feet. This was accomplished by the opening and closing of wickets, or iron gates. The lock that Volunteer goes through is number 44. Upon entering it, you will see that the doors in front of you, called whalers, are closed. The canalboat’s crew then closes the ones behind you and in about ten minutes the water level rises roughly three feet. We were warned that this process can make some seasick, and during the years of the canal’s operation, passengers so afflicted usually got off the boat before it entering the lock, then got back on after it exited. No one the day I went lost their lunch.

In nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most canal boats were about eighty feet long with the middle section being reserved for the mules that pulled the boat. Many canal boat owners had two pairs because mules refused to work longer than six hours, so they had to be swapped out. Some boat captains rented them from local farmers. I was told that steam engines were never used on Miami & Erie canalboats, although they certainly were on the rival Ohio & Erie Canal.

Although it’s true that railroads took a lot of business from canals, they were still profitable enough that the Miami & Ohio was refurbished between 1906 to 1909. A statewide flood of Biblical proportions in 1913 destroyed much of Ohio’s canal system, and it’s at that point canalboats stopped plying it. Surviving sections were often repurposed for other uses.

The Miami & Erie Canal runs along the side of the Maumee River, and it’s at the latter that Peter Manor, a French-Canadian, built a sawmill and founded the town of Providence. The sawmill stood in the way of what would become the Miami & Erie, so Manor sold it and the land it stood on in exchange for perpetual water rights. He began building a new mill along the new canal itself but died of cholera in 1849 before its completion.

Although it’s true that railroads took a lot of business from canals, they were still profitable enough that the Miami & Ohio was refurbished between 1906 to 1909. A statewide flood of Biblical proportions in 1913 destroyed much of Ohio’s canal system, and it’s at that point canalboats stopped plying it. Surviving sections were often repurposed for other uses.

The Miami & Erie Canal runs along the side of the Maumee River, and it’s at the latter that Peter Manor, a French-Canadian, built a sawmill and founded the town of Providence. The sawmill stood in the way of what would become the Miami & Erie, so Manor sold it and the land it stood on in exchange for perpetual water rights. He began building a new mill along the new canal itself but died of cholera in 1849 before its completion.

There the unfinished building stood for nineteen years until boat builder and skilled carpenter Isaac Ludwig bought it from Mason’s son, Frank, in 1866. Ludwig also acquired Mason’s perpetual water rights. Powered by a waterwheel along the Maumee River, Ludwig’s venture started out as a sawmill, then was transformed into a gristmill in the 1880s that ground corn, wheat and buckwheat into flour. Ludwig hired Augustine Pilliod, a miller, to oversee this operation. The millstones used to perform this task were made out of French granite, which at the time was considered the best in the world for this purpose.

Pilliod bought the mill from Ludwig in 1886. He replaced its inefficient waterwheel with a turbine that got its water from a millrace that sent it into the penstock beneath the building. The millrace’s starting point was at the nearby Providence Dam, which was built in 1840. Although you can visit the penstock, beware: it’s filled with a surplus of spiders.

Pilliod bought the mill from Ludwig in 1886. He replaced its inefficient waterwheel with a turbine that got its water from a millrace that sent it into the penstock beneath the building. The millrace’s starting point was at the nearby Providence Dam, which was built in 1840. Although you can visit the penstock, beware: it’s filled with a surplus of spiders.

Although Metroparks Toledo restored the mill so it represents how it operated in 1900, it has an anachronism: a fifty-six inch circular saw was added that is used to cut logs down for use in Metroparks construction projects. The saw is powered by a forty-eight inch Trump turbine. A thirty-six inch Leffel turbine drives the grindstones on the second floor. Because it’s water source of the Maumee River, the saw and grindstones can run even when the canal freezes, although too much water renders the mill’s turbines useless, stopping operations. In 1902, Pilliod added a boiler and steam engine to the mill to produce electricity, the surplus of which he sold to Grand Rapids until 1915.

Pilliod hired Frank Heising, who spoke both English and German, as a translator and, because of his size and strength, also used him as a human forklift. Heising could toss 125 pound bags of grain without breaking a sweat, earning him the appellation the “Dutch Elevator.” He bought the mill from Pilliod in 1919. During his tenure, says an information sign, he “invented self-rising pancake flour and buckwheat pancake flour,” the latter a favorite of the author’s. Upon Frank’s death in 1931, his son, Cleo, took over.

Pilliod hired Frank Heising, who spoke both English and German, as a translator and, because of his size and strength, also used him as a human forklift. Heising could toss 125 pound bags of grain without breaking a sweat, earning him the appellation the “Dutch Elevator.” He bought the mill from Pilliod in 1919. During his tenure, says an information sign, he “invented self-rising pancake flour and buckwheat pancake flour,” the latter a favorite of the author’s. Upon Frank’s death in 1931, his son, Cleo, took over.

Gristmills produce a lot of flour dust, and to keep it down, Pilliod introduced a dust collector to sweep it up, then sold this as pastry flour. Even with this machine, it’s impossible to catch it all, and flour dust in sufficient quantities can be explosive. It’s likely its presence is the reason the top two floors of the mill caught fire in 1940, a conflagration whose cause no one knows.

After rebuilding, Cleo switched to producing livestock feed, and this was the mill’s undoing. By 1972 demand for it had evaporated, so it shut down and nearly all its equipment was sold off. Isaac Ludwig’s great-grandson, Cleo Ludwig, bought it, then donated it to Metroparks Toledo with two conditions: it had to be named the Isaac Ludwig Mill, and had to be open to the public. The mill’s perpetual water rights also went to the Metroparks.🕜

After rebuilding, Cleo switched to producing livestock feed, and this was the mill’s undoing. By 1972 demand for it had evaporated, so it shut down and nearly all its equipment was sold off. Isaac Ludwig’s great-grandson, Cleo Ludwig, bought it, then donated it to Metroparks Toledo with two conditions: it had to be named the Isaac Ludwig Mill, and had to be open to the public. The mill’s perpetual water rights also went to the Metroparks.🕜

Grain, flours and meals that go into or come out of gristmills.

Lock Opening Up

View of the Canal

Mill Generator

Isaac Ludwig Mill's Office

Millstone Made from French Granite