Senator John Heinz History Center

Museum Entrance

Heinz Products

Restored Heinz Wagon Built in in the 1800s

This photo of the museum's side gives you an idea of just how large this place is.

Queen Aliquippa

1936 Stainless Steel Ford

Fruit Bowl Made by Tiffany & Co. (1903)

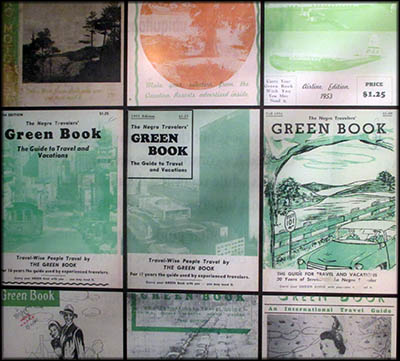

Covers From Various Edition of the Negro Motorist Green-Book

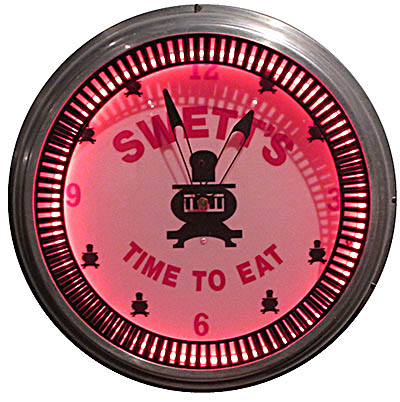

Swett's Diner opened in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1954. Founded by Walter and Susie Sweet, it was listed in the Green-Books and is still open today. This clock once hung in the original dinette, which was replaced by larger premises in the 1980s.

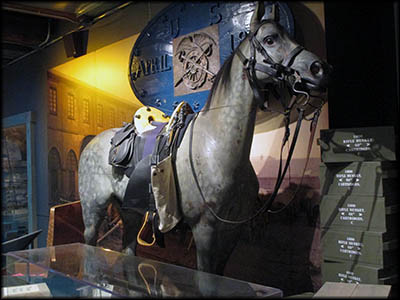

Horses carried the ammunition made in Pittsburgh for the Union Army during the Civil War.

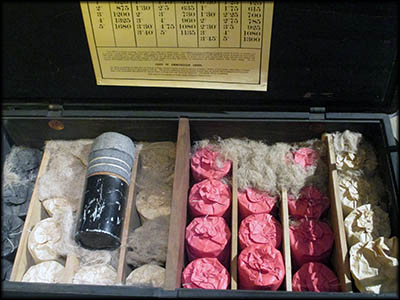

Civil War Ammunition Case

Replica of a 19th Century Pittsburgh Street

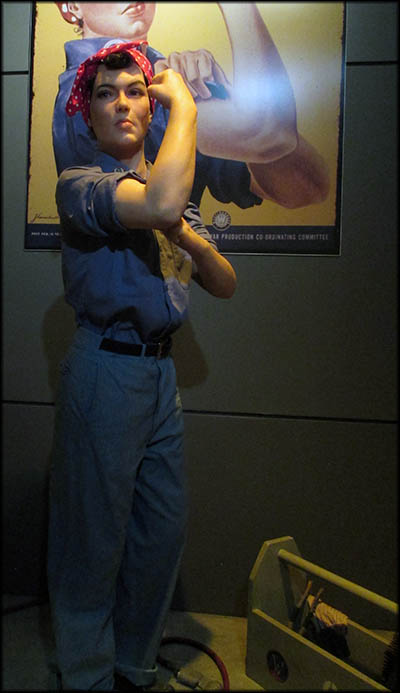

Rosie the Riveter was created by Pittsburgh-based Westinghouse artist J. Howard Miller in 1942. She was based on the likeness of a Michigan factory worker. She wouldn't be called "Rosie the Riveter" until a song and Normal Rockwell painting on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post popularized that name.

Martin Robison Delany

Jazz pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams

The PBS show Mister Rogers' Neighborhood was produced in Pittsburgh in the WQED studios.

On the museum's 5th floor there is an excellent display about the French and Indian War, which I declined to mention in this travel log because it's covered in those about Fort Necessity and Fort Pitt.

Heinz Ads

Exhibit Sign

On the day a friend and I visited the Fort Pitt Museum in Pittsburgh (for which I wrote this travel log), we were told that if we presented our admission receipt at the Senator John Heinz History Center, we’d receive an $8 discount. It turned out the Heinz History Center also ran the Fort Pitt Museum as well as Meadowcroft Rockshelter and Historic Village. So we went not knowing what we were getting into. This Heinz History Center is huge. Of its six floors, five are packed full of exhibits. The sixth houses the Detre Library and Archives. Some floors do have parts reserved for other functions that include the Weisbrod Kitchen Classroom and Mueller Education Center.

“Senator John Heinz History Center” is a bit of mouthful for a museum name, so I figured whoever this fellow was, he must’ve started the place. Not so. Born Henry John Heinz, he was one Pennsylvania’s U.S. senators from 1976 to 1991. His career and life ended in a fiery airplane-helicopter in-air collision that unfortunately crashed into a school, killing two students. He was one of the heirs to the fortune H. J. Heinz Company fortune, which is now Kraft Heinz.

The museum started as 1879 as a historical society called the Old Residents of Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania, which was renamed to the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania five years later. In 1996, it moved its premises to the remodeled building that once served home to the Chautauqua Lake Ice Company. It was at this time that the museum took on its current appellation. In 2000, it began its continuing collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution.

“Senator John Heinz History Center” is a bit of mouthful for a museum name, so I figured whoever this fellow was, he must’ve started the place. Not so. Born Henry John Heinz, he was one Pennsylvania’s U.S. senators from 1976 to 1991. His career and life ended in a fiery airplane-helicopter in-air collision that unfortunately crashed into a school, killing two students. He was one of the heirs to the fortune H. J. Heinz Company fortune, which is now Kraft Heinz.

The museum started as 1879 as a historical society called the Old Residents of Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania, which was renamed to the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania five years later. In 1996, it moved its premises to the remodeled building that once served home to the Chautauqua Lake Ice Company. It was at this time that the museum took on its current appellation. In 2000, it began its continuing collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution.

On the museum’s first floor you’ll see the Great Hall. This is filled with all sorts of interesting including the Heinz Hitch Wagon. Built in the nineteenth century by Studebaker in South Bend, Indiana, it was originally used to deliver Heinz’s products until being put into storage and forgotten about. When rediscovered in 1978, a tree was growing though it. Restored, it was taken around the United States as a showcase for the company from 1986 to 2006, and it often appeared in major parades.

Another item that caught my eye was the 1936 Ford DeLuxe Sedan made out of stainless steel. This isn’t the only American stainless steel car made before the DeLorean—I saw some at the Cleveland History Center—but the body for this particular one was made by Allegheny Steel. Ford used it to showcase the superiority of stainless steel and its resistance to rust and weather. Six that were made, and this particular one was retired as a demonstration model in 1946.

Also on the first floor was an exhibit about the origin and history of the Negro Motorist Green-Book by Victor H. Green. Green was a postal carrier, a career he worked in from 1913 until his retirement in 1952. Born on November 9, 1892, in Manhattan, he was raised in Hackensack, New Jersey, where he worked all his life. In 1918, he moved residence to Harlem after marrying Alma Duke, who was originally from Richmond, Virginia.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, states and municipalities across the United States introduced Jim Crow laws—statutes meant to control and degrade Blacks to ensure that they remained an underclass with less privileges than the poorest whites. Although certainly the worst of these laws were passed and strictly enforced in former Confederate states, they weren’t limited to that geographic region. Many municipalities were known as “sundown towns” that forbade African Americans from being on the streets after dark, such as Levittown, NY, Glendale, CA, as well as most of the towns and cities in Illinois.

Another item that caught my eye was the 1936 Ford DeLuxe Sedan made out of stainless steel. This isn’t the only American stainless steel car made before the DeLorean—I saw some at the Cleveland History Center—but the body for this particular one was made by Allegheny Steel. Ford used it to showcase the superiority of stainless steel and its resistance to rust and weather. Six that were made, and this particular one was retired as a demonstration model in 1946.

Also on the first floor was an exhibit about the origin and history of the Negro Motorist Green-Book by Victor H. Green. Green was a postal carrier, a career he worked in from 1913 until his retirement in 1952. Born on November 9, 1892, in Manhattan, he was raised in Hackensack, New Jersey, where he worked all his life. In 1918, he moved residence to Harlem after marrying Alma Duke, who was originally from Richmond, Virginia.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, states and municipalities across the United States introduced Jim Crow laws—statutes meant to control and degrade Blacks to ensure that they remained an underclass with less privileges than the poorest whites. Although certainly the worst of these laws were passed and strictly enforced in former Confederate states, they weren’t limited to that geographic region. Many municipalities were known as “sundown towns” that forbade African Americans from being on the streets after dark, such as Levittown, NY, Glendale, CA, as well as most of the towns and cities in Illinois.

Southern states effectively became police states for Blacks. With that and limited opportunities to make a decent living, about six million African Americans migrated to the North in the first half of the twentieth century. At the same time cars became the primary means of transportation and improved roads meant that Blacks who’d moved to the North could travel back home to visit relatives. Or possibly just travel for leisure. But this was exceedingly dangerous for African Americans, and some who went on road trips disappeared. If the Ku Klux Klan didn’t get you, the police might. Others found it humiliating when told they couldn’t stay at a certain motel or eat at a particular restaurant. Aware of this, Green wrote his first Green Book specifically for Black visitors to New York that told them where they could safely stay, eat, and buy gas.

The book’s popularity prompted Green to expand its reach to other parts of the United States. He did this by using contacts with Black postmen across the country as well as contributions from people who traveled there. First published in 1936, it originally limited itself to hotels, restaurants and gas stations, but soon added houses that accepted Black guests plus a wide range of other businesses. It also included, according to a museum information sign, “articles, humor pieces, travel tips, advertising, and eventually political thought.”

In its early days, it was sold by mail order and at African American businesses. But that would soon change. At this time one of the largest gas station chains in the United States was Esso, which was owned by Standard Oil (now Exxon-Mobile). Standard Oil’s founder, John D. Rockefeller, was married to Laura Spelman, whose parents were abolitionists whose house was an Underground Railroad station. It’s possible that she injected a culture of openness towards Blacks at that company. This may explain why in 1927 it hired an African American, James A. Jackson, to, an information sign says, “research the roll and impact of the Black consumer in America.” Jackson and Green launched a plan to sell the Green Book at Esso stations, greatly increasing its availability.

The book’s popularity prompted Green to expand its reach to other parts of the United States. He did this by using contacts with Black postmen across the country as well as contributions from people who traveled there. First published in 1936, it originally limited itself to hotels, restaurants and gas stations, but soon added houses that accepted Black guests plus a wide range of other businesses. It also included, according to a museum information sign, “articles, humor pieces, travel tips, advertising, and eventually political thought.”

In its early days, it was sold by mail order and at African American businesses. But that would soon change. At this time one of the largest gas station chains in the United States was Esso, which was owned by Standard Oil (now Exxon-Mobile). Standard Oil’s founder, John D. Rockefeller, was married to Laura Spelman, whose parents were abolitionists whose house was an Underground Railroad station. It’s possible that she injected a culture of openness towards Blacks at that company. This may explain why in 1927 it hired an African American, James A. Jackson, to, an information sign says, “research the roll and impact of the Black consumer in America.” Jackson and Green launched a plan to sell the Green Book at Esso stations, greatly increasing its availability.

The Green Book ceased publication in 1966 because the need for it was over thanks to the gains of the Civil Rights Movement—a day Green himself hoped for, although he didn’t see it. He died in 1960. While the “Negro Motorist Green Book” exhibit is well done and informative, it suffers from information overload. There are way too many information signs and if a person read everyone one, he or she wouldn’t have time to see the rest of the museum.

I consider the Smithsonian Institution one of the best museums in the United States (see my travel log here), a bar to which all others should aspire. That said, I’ve seen small town museums that are just as impressive, and I’ve been to one museum that is even better than the Smithsonian: The British Museum in London, England. In any case, the Heinz History Center greatly benefits from its association with the Smithsonian because it has the same top-notch exhibits you’d find at the core museum in Washington, D.C.

Let’s start with the full scale statues of historic figures. The three or four people who regularly read my travel logs will know that I think it’s corny (to put it politely) to dress up manikins and pretend that they make for a good display. If you don’t have the money for a real life-sized sculpture, then avoid such a display in the first place. (I make an exception for the display of historic outfits. That’s what manikins are for.) And so we come to the museum’s statue of Queen Aliquippa, which is what sculptures need to look like when used as part of an exhibit.

I consider the Smithsonian Institution one of the best museums in the United States (see my travel log here), a bar to which all others should aspire. That said, I’ve seen small town museums that are just as impressive, and I’ve been to one museum that is even better than the Smithsonian: The British Museum in London, England. In any case, the Heinz History Center greatly benefits from its association with the Smithsonian because it has the same top-notch exhibits you’d find at the core museum in Washington, D.C.

Let’s start with the full scale statues of historic figures. The three or four people who regularly read my travel logs will know that I think it’s corny (to put it politely) to dress up manikins and pretend that they make for a good display. If you don’t have the money for a real life-sized sculpture, then avoid such a display in the first place. (I make an exception for the display of historic outfits. That’s what manikins are for.) And so we come to the museum’s statue of Queen Aliquippa, which is what sculptures need to look like when used as part of an exhibit.

She was a Seneca who lived in western Pennsylvania and by the 1740s was the matriarch of about thirty families. The Seneca were part of the Iroquois Confederation, a staunch ally of the British. If you wanted to deal with the Iroquois in the region, you went to her. That’s what George Washington did during his ill-fated expedition to oust the French from the region that ended with his defeat at Fort Necessity on July 3, 1754. She and her son were at that battle. Afterward, says a museum information sign, they “fled to George Croghan’s homestead where she died on December 23, 1754.”

One of the museum’s highlights is its coverage of Pittsburgh’s history. Some of it is the stuff you find in your standard history school book, such as the Whiskey Rebellion. In an effort to pay off the nation’s debt, Alexander Hamilton prompted Congress to pass a tax on the sale of whiskey, which those in Western Pennsylvania didn’t take too kindly to. Transporting cereal crops to sell in the East wasn’t profitable, but moving whiskey there was. It didn’t help that many of the whiskey producers had come from Scotland where they’d long fought the British over taxing their alcohol. The rebellion ended when President George Washington formed an army to suppress it. The rebels, knowing what was coming, made peace before it marched.

It’s the lesser known stuff that I found most interesting. Pittsburgh, for example, produced the world’s first iron-hulled, armored war ship: the steam powered USS Michigan. Her hull was built in 1843 by Pittsburgh’s Stackhouse & Tomlinson. She was taken in pieces to Erie, Pennsylvania, and there assembled and launched into Lake Erie. In 1905 she was renamed the USS Wolverine. Her career ended on August 12, 1923.

One of the museum’s highlights is its coverage of Pittsburgh’s history. Some of it is the stuff you find in your standard history school book, such as the Whiskey Rebellion. In an effort to pay off the nation’s debt, Alexander Hamilton prompted Congress to pass a tax on the sale of whiskey, which those in Western Pennsylvania didn’t take too kindly to. Transporting cereal crops to sell in the East wasn’t profitable, but moving whiskey there was. It didn’t help that many of the whiskey producers had come from Scotland where they’d long fought the British over taxing their alcohol. The rebellion ended when President George Washington formed an army to suppress it. The rebels, knowing what was coming, made peace before it marched.

It’s the lesser known stuff that I found most interesting. Pittsburgh, for example, produced the world’s first iron-hulled, armored war ship: the steam powered USS Michigan. Her hull was built in 1843 by Pittsburgh’s Stackhouse & Tomlinson. She was taken in pieces to Erie, Pennsylvania, and there assembled and launched into Lake Erie. In 1905 she was renamed the USS Wolverine. Her career ended on August 12, 1923.

Before the Civil War, many free African Americans living in the South moved to the North for better opportunities. To be sure there was still terrible racism, but it wasn’t so engrained that African Americans couldn’t make something of themselves here and there. Martin Robison Delany is example. Born and raised in Charles Town, Virginia, in 1812, he moved to Pittsburgh in 1831 where he started the abolitionist newspaper The Mystery. It was the first Black newspaper west of the Allegheny Mountains. According to a museum information sign, “he used The Mystery to foster Black pride and institutions such as schools and churches, as well as providing information to freedom seekers and free Blacks.”

He had more ambitions than just running a newspaper. In 1850, he applied to Harvard Medical School. Its dean, Oliver Wendell Holmes, accepted Delany’s application along with two other African Americans: Daniel Laing, Jr. and Isaac Humphrey Snowden. Harvard’s racist white students were having none of that and managed to get the three barred from lectures. Snowden and Laing left for the American colony of Liberia. Delany went to New York to earn his medical degree. Returning to Pittsburgh in 1853, the next year he was one of the few doctors to treat patients during a cholera outbreak.

After his experience at Harvard, Delany became a proponent of the mass emigration of Blacks from the United States to other locations. He traveled of West Africa in 1859 to investigate it as a possible location. He changed his mind about Blacks migrating elsewhere when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This prompted Delany to recruit African Americans into the Union Army, which he himself joined. Lincoln appointed him a major in the 104th United States Colored Commission in 1865, making him the highest ranking African American in the Union army.

He had more ambitions than just running a newspaper. In 1850, he applied to Harvard Medical School. Its dean, Oliver Wendell Holmes, accepted Delany’s application along with two other African Americans: Daniel Laing, Jr. and Isaac Humphrey Snowden. Harvard’s racist white students were having none of that and managed to get the three barred from lectures. Snowden and Laing left for the American colony of Liberia. Delany went to New York to earn his medical degree. Returning to Pittsburgh in 1853, the next year he was one of the few doctors to treat patients during a cholera outbreak.

After his experience at Harvard, Delany became a proponent of the mass emigration of Blacks from the United States to other locations. He traveled of West Africa in 1859 to investigate it as a possible location. He changed his mind about Blacks migrating elsewhere when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This prompted Delany to recruit African Americans into the Union Army, which he himself joined. Lincoln appointed him a major in the 104th United States Colored Commission in 1865, making him the highest ranking African American in the Union army.

During the Civil War, Pittsburgh produced much of the war material used by the North. The Alleghany Arsenal, as an example, made everything from bullets to saddles to horse-drawn limbers. In addition to having the infrastructure and ability to fuel the war effort, Pittsburgh’s location was equally important. From here all that was produced could be transported to the war’s western theater via the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

Pittsburgh couldn’t have become an industrial powerhouse without the railroads. But this mode of transportation wasn’t exactly safe to ride on throughout much of the nineteenth century. Two major inventions that came out of Pittsburgh helped to improve that. In 1872, New Jersey inventor William Robinson came to the city to showcase his new signaling system that would make train travel much safer by using electric signals to detect trains in one place and send an alert that they were coming to another. Complementing this, Pittsburgh-based inventor George Westinghouse invented air brakes. These allowed trains to stop faster because all the cars stopped simultaneously. Before this invention, brakemen had to manually tighten the brakes on each individual car. Westinghouse, who founded the Westinghouse Company, bought Robinson’s patent and used it as the basis for a new company in 1881: Union Switch & Signal.

Westinghouse was also a promoter of alternating current (AC), which is superior to direct current (DC) because it can be transmitted over long distances without losing its strength. Thomas Edison based his electric system on direct current and, seeing AC as a rival, tried to convince the public that AC was too dangerous to use. His efforts inspired electrical engineer Harold P. Brown to use AC to electrocute animals, something Edison also did. Despite opposing the death penalty, Edison secretly financed Brown’s construction of the world’s first electric chair, a particularly unpleasant way to kill humans. AC won the “War of the Currents” when Westinghouse powered all the electric lights at the 1893 World’s Fair, showing it could safely do so.

Pittsburgh couldn’t have become an industrial powerhouse without the railroads. But this mode of transportation wasn’t exactly safe to ride on throughout much of the nineteenth century. Two major inventions that came out of Pittsburgh helped to improve that. In 1872, New Jersey inventor William Robinson came to the city to showcase his new signaling system that would make train travel much safer by using electric signals to detect trains in one place and send an alert that they were coming to another. Complementing this, Pittsburgh-based inventor George Westinghouse invented air brakes. These allowed trains to stop faster because all the cars stopped simultaneously. Before this invention, brakemen had to manually tighten the brakes on each individual car. Westinghouse, who founded the Westinghouse Company, bought Robinson’s patent and used it as the basis for a new company in 1881: Union Switch & Signal.

Westinghouse was also a promoter of alternating current (AC), which is superior to direct current (DC) because it can be transmitted over long distances without losing its strength. Thomas Edison based his electric system on direct current and, seeing AC as a rival, tried to convince the public that AC was too dangerous to use. His efforts inspired electrical engineer Harold P. Brown to use AC to electrocute animals, something Edison also did. Despite opposing the death penalty, Edison secretly financed Brown’s construction of the world’s first electric chair, a particularly unpleasant way to kill humans. AC won the “War of the Currents” when Westinghouse powered all the electric lights at the 1893 World’s Fair, showing it could safely do so.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Pittsburgh wasn’t a healthy place to live. Smoke from steel mills and other industries blanketed it. There wasn’t a clean water system, leading to outbreaks of water-born diseases like typhoid, which killed more than 7,000 between 1883 and 1907. The creation of a water treatment plant in 1908 and the expansion of running water in every home helped significantly reduce disease. There was still an issue with raw sewage, which Pittsburgh didn’t do something about until 1958 when it opened its first sewage treatment plant.

Pittsburgh and the surrounding area were dangerous to work in as well. Industries didn’t care about safety and treated workers as expendable. One of the worst places to work was in a coal mine. The thing coal miners feared above all else was an explosion. These often created poisonous gases called afterdamp just as deadly as the explosion, and making rescue a dangerous venture. The German company Dräger Oxygen Apparatus Company invented a breathing device that dealt with this, allowing rescuers to safely look for survivors after an explosion. The company moved its headquarters to Pittsburgh.

I learned this and much more mainly from the “Pittsburgh: A Tradition of Innovation” exhibit on the second floor. On the fourth floor is an exhibit that traces the origin and history of the H.J. Heinz Company. The curators who created this were geniuses: they made what sounds like a dry subject interesting. The H.J. Heinz Company was founded in by Henry John Heinz and partner L. Clarence Noble in 1869 in the borough of Sharpsburg, which is on the north side of the Allegheny River across from Pittsburgh. It began as a horseradish, pickle and sauerkraut producer called Anchor Pickle and Vinegar Works, then changed its name to Heinz & Noble. The Panic of 1873 put it out of business, but undaunted, Heinz restarted with the financing from his cousin Frederick and brother John. F. &. J. Heinz opened business in 1876. Henry bought out his partners in 1888, then renamed the company H.J. Heinz.

Pittsburgh and the surrounding area were dangerous to work in as well. Industries didn’t care about safety and treated workers as expendable. One of the worst places to work was in a coal mine. The thing coal miners feared above all else was an explosion. These often created poisonous gases called afterdamp just as deadly as the explosion, and making rescue a dangerous venture. The German company Dräger Oxygen Apparatus Company invented a breathing device that dealt with this, allowing rescuers to safely look for survivors after an explosion. The company moved its headquarters to Pittsburgh.

I learned this and much more mainly from the “Pittsburgh: A Tradition of Innovation” exhibit on the second floor. On the fourth floor is an exhibit that traces the origin and history of the H.J. Heinz Company. The curators who created this were geniuses: they made what sounds like a dry subject interesting. The H.J. Heinz Company was founded in by Henry John Heinz and partner L. Clarence Noble in 1869 in the borough of Sharpsburg, which is on the north side of the Allegheny River across from Pittsburgh. It began as a horseradish, pickle and sauerkraut producer called Anchor Pickle and Vinegar Works, then changed its name to Heinz & Noble. The Panic of 1873 put it out of business, but undaunted, Heinz restarted with the financing from his cousin Frederick and brother John. F. &. J. Heinz opened business in 1876. Henry bought out his partners in 1888, then renamed the company H.J. Heinz.

Henry created a competitive edge by selling directly to grocers instead of through a wholesaler. He tapped into the growing market for ready-made products. Instead of taking hours to make, say, jam, a person could buy it off the shelf. He made sure the quality and flavor of his products remain as consistent as possible. He was ahead of his time in that he was keen on keeping things hygienic.

Henry built a factory in Pittsburgh. If it was anything like the one I used to pass on the Route 20 bypass around Fremont, Ohio, it smelled pretty awful. The one in Fremont makes ketchup, and it emits an unpleasant odor during the tomato harvest. He hired mostly women because he could pay them less. They wore uniforms that included a white cap, which in and of itself became part of the company’s branding. From 1899 until 1927, the company offered tours of the facility. The company sold the factory to Del Monte in in 2002. It’s since been made into apartments and is called Heinz Lofts.

Henry invested heavily in advertising. His salesforce went into grocers that sold his products and created displays, provided signs, and even gave out trade cards. Packaging in and of itself had to be attractive. Another promotional innovation was the clear glass vinegar dispenser that allowed customers to sample the different varieties before purchasing the one to their taste. H.J. Heinz also sold products to restaurants, an area of business the company stayed in long after Henry’s death in 1919. In 1968, the company invented the single-serve ketchup package for use in fast food restaurants.

At the 1893 Columbiana Exposition in Chicago, the Heinz exhibit was on the second floor in the Agricultural Building. Being a low traffic area, Heinz exhibitors needed something to attract visitors. They passed out tags in other parts of the fair offering free food samples and a pickle charm, the latter evolving into today’s pickle pin. The ploy worked. Hundreds of thousands came. The company did something similar on pier in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Here glass pavilion free to enter was built that featured glassware, oil paintings, and other items visitors could ogle over. The real purpose was further Heinz’s popularity by giving out samples, handing out free postcards with the Heinz logo, and offering presentations about the company’s business.

In 1896, Henry saw an advertisement that said, “21 Styles of Shoes,” and he thought a number like that would work for his company. He settled on the arbitrary number fifty-seven because he thought it sounded good. (His company made more products than that.) In 1900, the company debuted the world’s first electric sign, or really several of them put together on the side of a skyscraper with that number on it. It was lit up using 1,200 incandescent lights. Trademarked, “57” was slapped on all products and ads and used extensively until 1969.

His company expanded oversees in February 1902 when star salesman Alexander MacWillie set sail out of San Francisco for the Eastern Hemisphere. While in Australia, he decided to start in-store demonstrations using a twenty-one-year-old American woman named Margaret McLeod because he rightly guessed that a pretty young blond would attract more attention than the actual products. He took her along to Japan, South Africa and India.🕜

Henry built a factory in Pittsburgh. If it was anything like the one I used to pass on the Route 20 bypass around Fremont, Ohio, it smelled pretty awful. The one in Fremont makes ketchup, and it emits an unpleasant odor during the tomato harvest. He hired mostly women because he could pay them less. They wore uniforms that included a white cap, which in and of itself became part of the company’s branding. From 1899 until 1927, the company offered tours of the facility. The company sold the factory to Del Monte in in 2002. It’s since been made into apartments and is called Heinz Lofts.

Henry invested heavily in advertising. His salesforce went into grocers that sold his products and created displays, provided signs, and even gave out trade cards. Packaging in and of itself had to be attractive. Another promotional innovation was the clear glass vinegar dispenser that allowed customers to sample the different varieties before purchasing the one to their taste. H.J. Heinz also sold products to restaurants, an area of business the company stayed in long after Henry’s death in 1919. In 1968, the company invented the single-serve ketchup package for use in fast food restaurants.

At the 1893 Columbiana Exposition in Chicago, the Heinz exhibit was on the second floor in the Agricultural Building. Being a low traffic area, Heinz exhibitors needed something to attract visitors. They passed out tags in other parts of the fair offering free food samples and a pickle charm, the latter evolving into today’s pickle pin. The ploy worked. Hundreds of thousands came. The company did something similar on pier in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Here glass pavilion free to enter was built that featured glassware, oil paintings, and other items visitors could ogle over. The real purpose was further Heinz’s popularity by giving out samples, handing out free postcards with the Heinz logo, and offering presentations about the company’s business.

In 1896, Henry saw an advertisement that said, “21 Styles of Shoes,” and he thought a number like that would work for his company. He settled on the arbitrary number fifty-seven because he thought it sounded good. (His company made more products than that.) In 1900, the company debuted the world’s first electric sign, or really several of them put together on the side of a skyscraper with that number on it. It was lit up using 1,200 incandescent lights. Trademarked, “57” was slapped on all products and ads and used extensively until 1969.

His company expanded oversees in February 1902 when star salesman Alexander MacWillie set sail out of San Francisco for the Eastern Hemisphere. While in Australia, he decided to start in-store demonstrations using a twenty-one-year-old American woman named Margaret McLeod because he rightly guessed that a pretty young blond would attract more attention than the actual products. He took her along to Japan, South Africa and India.🕜